Testing the patient’s tactile sensation and other sensory qualities is important for assessing the patient’s condition. It can make it easier to determine whether the issue is centrally or peripherally related, the type of pain mechanism involved, and it can provide insights into which nerve fibers are affected.

Some basics

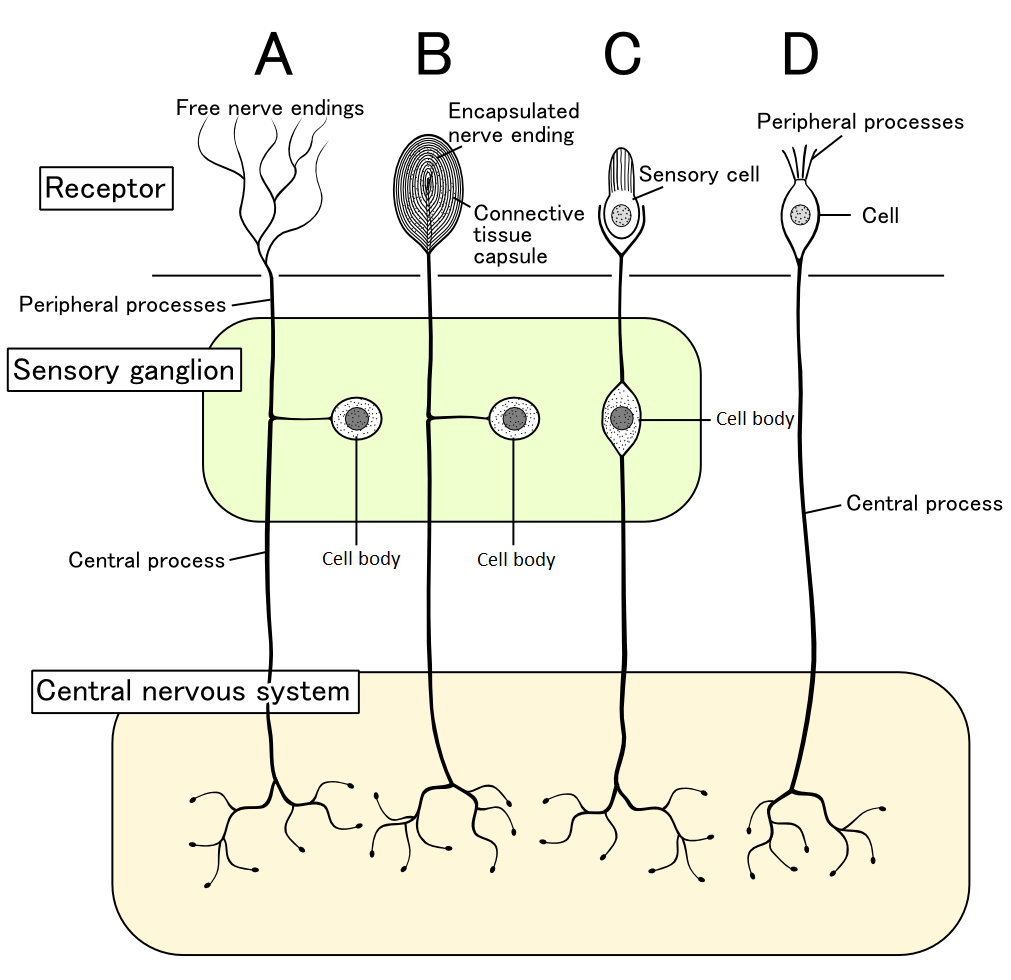

Sensory testing evaluates the somatosensory system. The term “somatosensory” encompasses all sensory experiences related to the body (soma), although it is now commonly used more narrowly to refer to sensory information from the skin, joints, and muscles. Receptors that detect this information are categorized into mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and chemoreceptors (1).

Receptors have different thresholds for activation. Low-threshold receptors respond very easily, such as to gentle touch on the skin (1). High-threshold receptors usually, but not always, respond to harmful stimuli. These high-threshold receptors are called nociceptors. Per Brodal suggests calling them homeceptors, which really is quite a descriptive term (2). Nociceptors monitor tissues and the mechanical and thermal forces they are exposed to (3). Many of the receptors don’t respond to just one stimulus but multiple ones, such as heat, mechanical, and chemical stimuli; these are called polymodal (3).

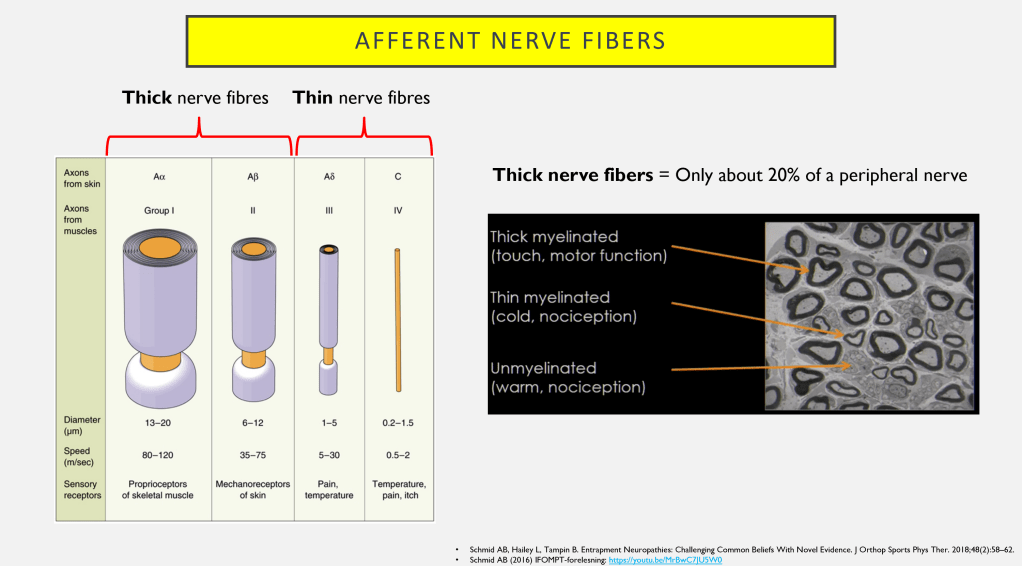

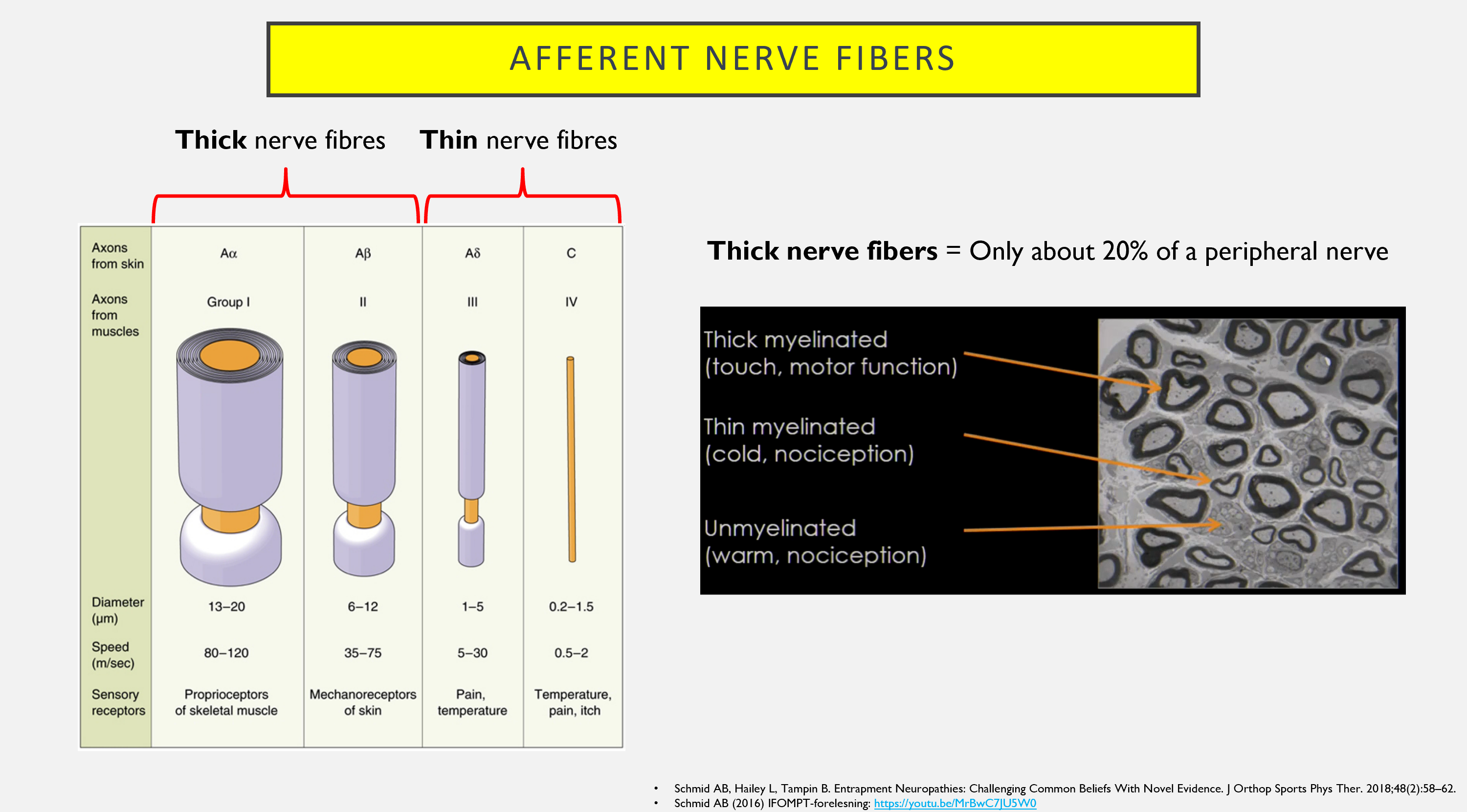

Different types of afferent stimuli are carried by different types of nerve fibers, and within sensory testing, the focus is primarily on A-beta, A-delta, and C-fibers (4).

A-beta

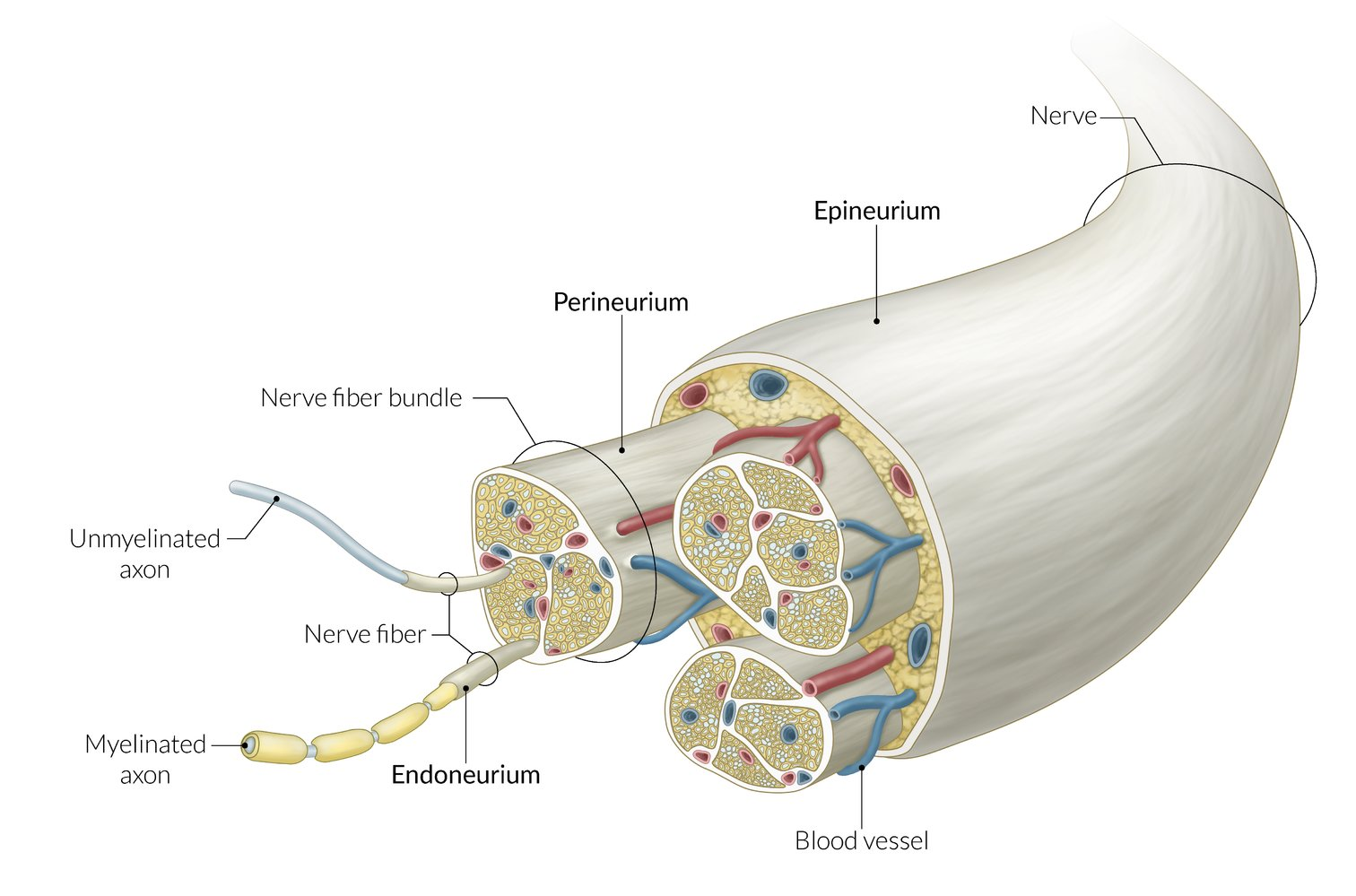

A-beta fibers are classified as thick nerve fibers, along with A-alfa (5). Thanks to the thick nerve fibres, you can close your eyes and know where your body is. For example, you can tell if there’s pressure on your buttocks and back when you sit on a chair, or you don’t need to look down when walking to know where your legs are. A-beta fibers are thickly myelinated and react to stimulus from low-threshold receptors, like with light touch. In a normal system they do not send out information that can be interpreted as pain (4). Traditional neurological tests typically evaluate only the thick nerve fibers. Early research on nerve damage involved animal studies with significant nerve damage. They found that acute injuries led to greater degeneration of the thick nerve fibers, while not much happened to the thin A-delta and C fibers. In recent times, research has focused more on long-term, low-grade pressure (which is more relevant to the average patient) and has observed greater degeneration of the thin nerve fibers. The thick nerve fibers become somewhat demyelinated but remain intact (6).

A-delta and C-fibers

A-delta and C-fibers are classified as thin nerve fibers. These are activated by potentially painful stimuli. A-delta is myelinated and, therefore, transmits impulses at high speed (4,5). These fibers are activated when, for example, you step on a Lego brick and need to quickly pull your foot back. The pain is often sharp and stabbing (1). A-delta nociceptors respond to both heat and mechanical stimuli – they are polymodal (7).

C-fibers are also classified as thin nerve fibers. Around 70% of nociceptors are associated with C-fibers. These fibers are not myelinated, resulting in a low conduction velocity (7). The pain experienced upon C-fiber activation is often described as a more “dull” sensation, typically following the rapid A-delta pain that occurs when you step on a Lego brick.

Of course, as we know, there is not a linear relationship between nociceptor activity and pain perception, and nociceptive input can occur without pain (3).

Why do sensory exam in suspected disc herniation and radiculopathy?

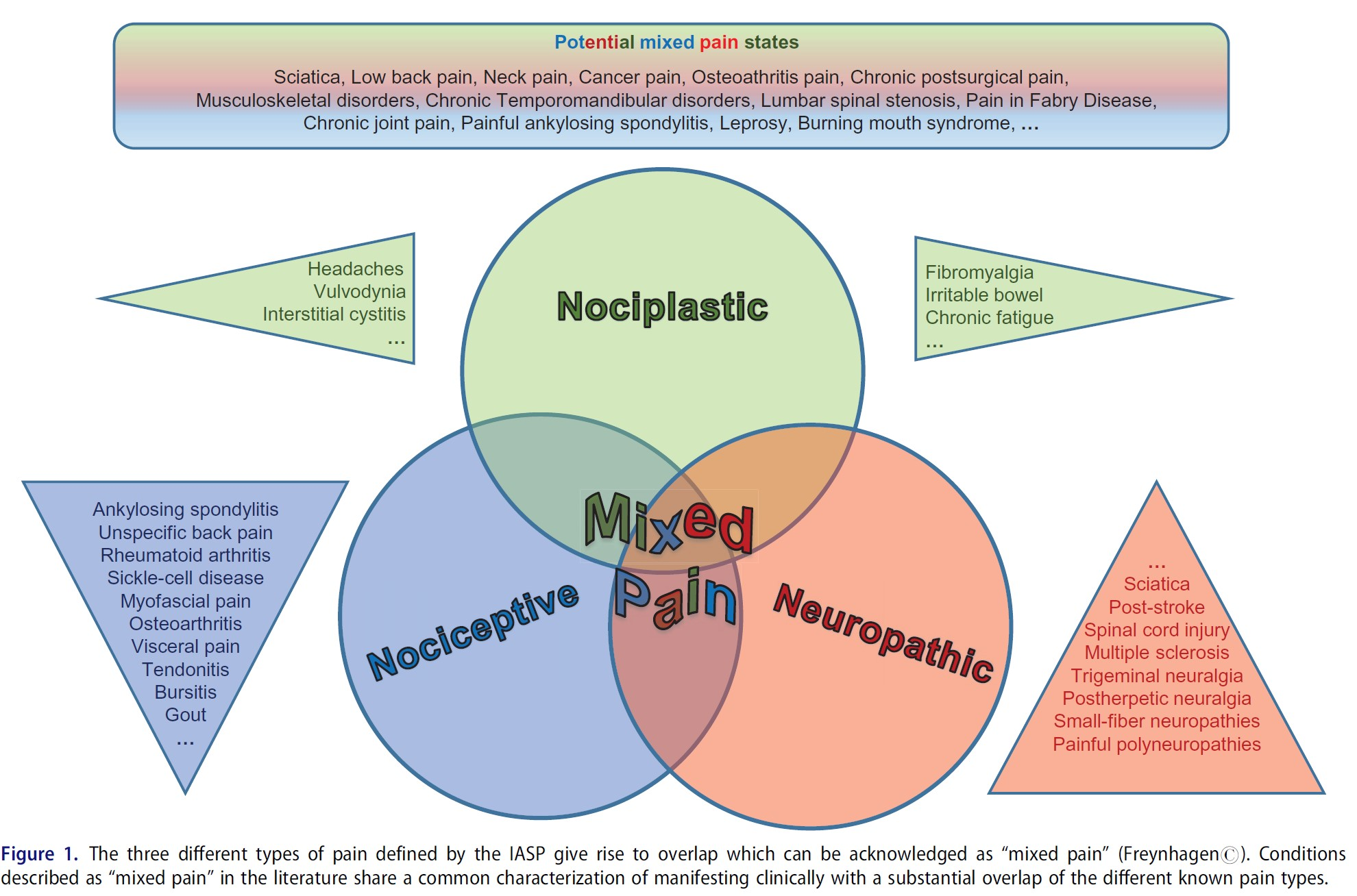

Testing the somatosensory system, including sensation, can provide valuable information. It can help differentiate the type of pain mechanism, classifying it as nociceptive, neuropathic, and/or nociplastic pain, possibly including “mixed pain” (9). Radicular pain is a form of neuropathic pain, just as radiculopathy is a form of neuropathy (10).

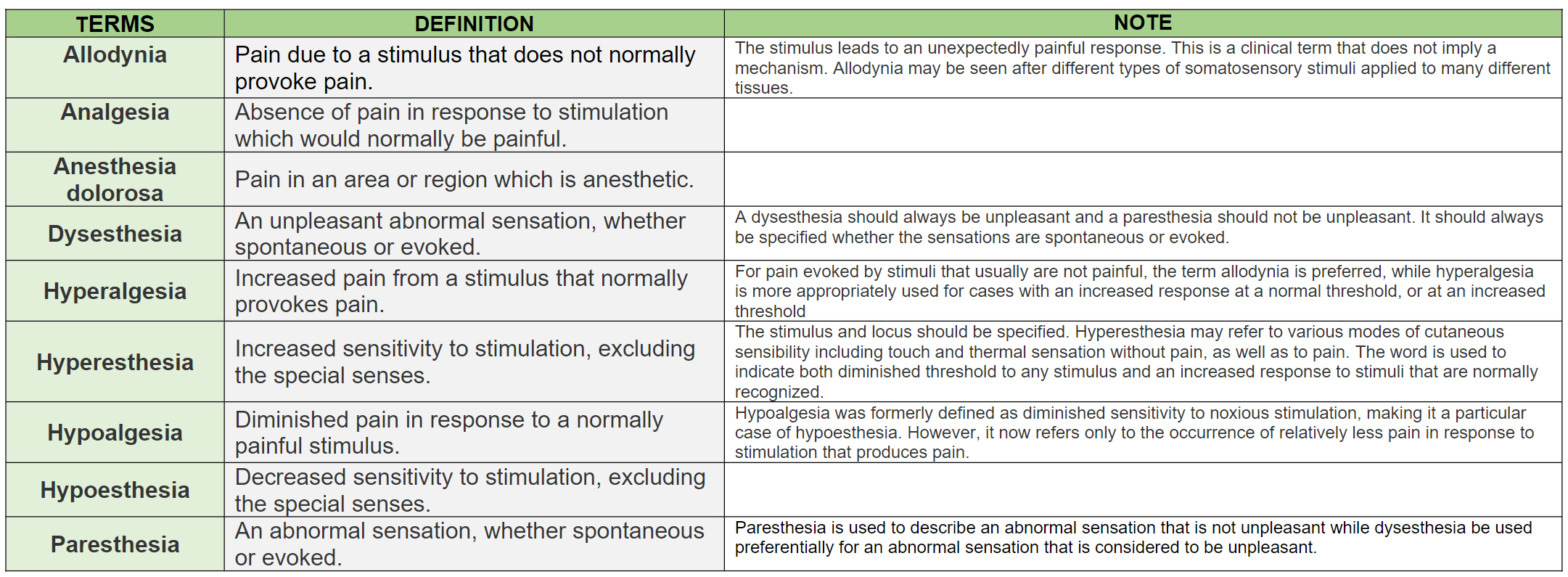

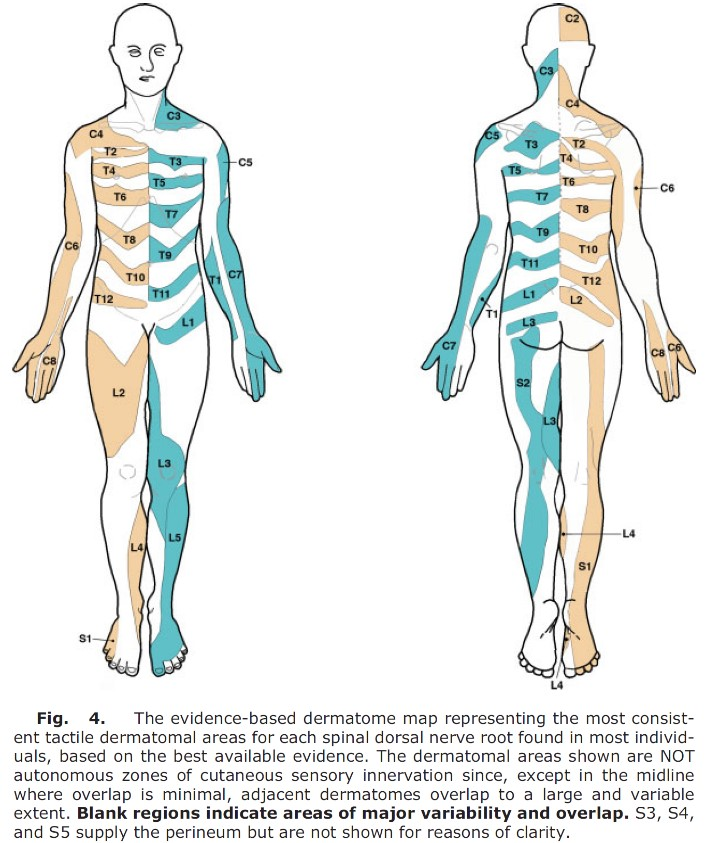

If there is decreased sensation in a dermatome, it may indicate nerve root involvement or damage, but it doesn’t necessarily indicate neuropathic/radicular pain. To assess whether it is radicular pain, the painful area must be tested. Results must be interpreted carefully, as positive findings like allodynia and hyperalgesia are also common in nociceptive pain conditions (11). Allodynia and hyperalgesia can also be present in both peripheral neuropathies and central pain conditions, and they are present in 15-50% of patients with neuropathic pain (12). Some negative findings (loss of function) have also been observed in non-neuropathic musculoskeletal disorders. In radiculopathy, there is often a clearer boundary for loss of function, while in more nociceptive disorders, the boundaries are more diffuse and not reproducible (11).

Although it can be difficult to interpret what is exactly happening in the patient during sensation testing, it provides valuable information if the patient has reduced nerve function in a dermatome corresponding to other findings in the neurological examination. This may suggest nerve root involvement (13,14).

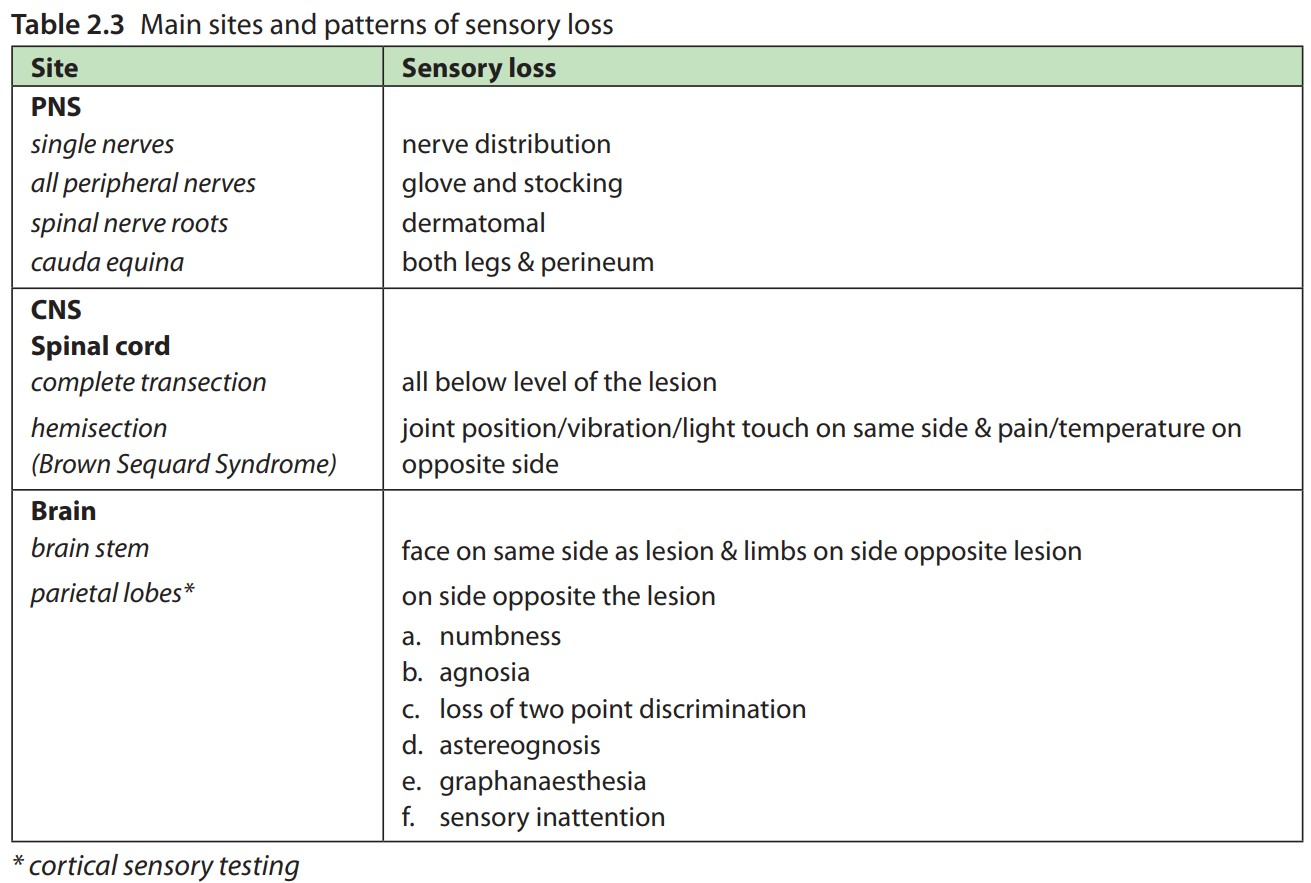

If multiple dermatomes are affected, and this follows the pattern of a peripheral nerve, it may indicate nerve involvement (13).

If the involvement extends to multiple peripheral nerves, it may suggest plexus or central nervous system involvement, and central nervous system involvement can lead to altered sensation in larger or smaller areas (13,15).

Summary

Sensation testing assesses the somatosensory system. Receptors that detect information are divided into mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and chemoreceptors. Low-threshold receptors respond very easily, such as to gentle touch on the skin. High-threshold receptors usually respond but not always to noxious stimuli. Different types of afferent stimuli are carried by different types of nerve fibers, and within sensation testing, the focus is primarily on A-beta, A-delta, and C-fibers. A-beta fibers are classified as thick nerve fibers, while A-delta and C-fibers are classified as thin nerve fibers. Pain mechanisms can be classified as nociceptive, neuropathic, and/or nociplastic pain

References

1. Brodal P. Sentralnervesystemet. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2013.

2. Jull G, Moore A, Falla D, Lewis J, McCarthy C, Sterling M, redaktører. Grieve’s modern musculoskeletal physiotherapy. 4th. ed. Edinburgh New York: Elsevier; 2015. 24 s.

3. Brodal P. A neurobiologist’s attempt to understand persistent pain. Scand J Pain. april 2017;15:140–7.

4. Lind P. Ryggen: undersøgelse og behandling af nedre ryg. 2. utg. Kbh.: Munksgaard Danmark; 2011.

5. Schibye B, Klausen K. Menneskets fysiologi: hvile og arbejde. Kbh.: FADL; 2012.

6. Schmid AB, Hailey L, Tampin B. Entrapment Neuropathies: Challenging Common Beliefs With Novel Evidence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):58–62.

7. Staehelin Jensen T, Dahl JB, Arendt-Nielsen L. Smerter: baggrund, evidens og behandling. Kbh.: FADL; 2013.

8. Chimenti RL, Frey-Law LA, Sluka KA. A Mechanism-Based Approach to Physical Therapist Management of Pain. Phys Ther. 1. mai 2018;98(5):302–14.

9. Freynhagen R, Parada HA, Calderon-Ospina CA, Chen J, Rakhmawati Emril D, Fernández-Villacorta FJ, mfl. Current understanding of the mixed pain concept: a brief narrative review. Curr Med Res Opin. juni 2019;35(6):1011–8.

10. Adebajo A, Fabule J. Management of radicular pain in rheumatic disease: insight for the physician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. juni 2012;4(3):137–47.

11. Schmid AB, Tampin B. Section 10, Chapter 10: Spinally Referred Back and Leg Pain – International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. I: Boden SD, redaktør. Lumbar Spine Online Textbook [Internett]. 2020 [sitert 4. oktober 2020]. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.wheelessonline.com/ISSLS/section-10-chapter-10-spinally-referred-back-and-leg-pain/

12. Jensen TS, Finnerup NB. Allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: clinical manifestations and mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 1. september 2014;13(9):924–35.

13. Solberg AS, Kirkesola G. Klinisk undersøkelse av ryggen. Kristiansand: HøyskoleForlaget; 2007.

14. Lee MWL, McPhee RW, Stringer MD. An evidence-based approach to human dermatomes. Clin Anat N Y N. juli 2008;21(5):363–73.

15. Howlett WP. Neurology in Africa: clinical skills and neurological disorders [Internett]. Bergen: University of Bergen; 2012 [sitert 20. januar 2021]. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.uib.no/cih/en/resources/neurology-in-africa