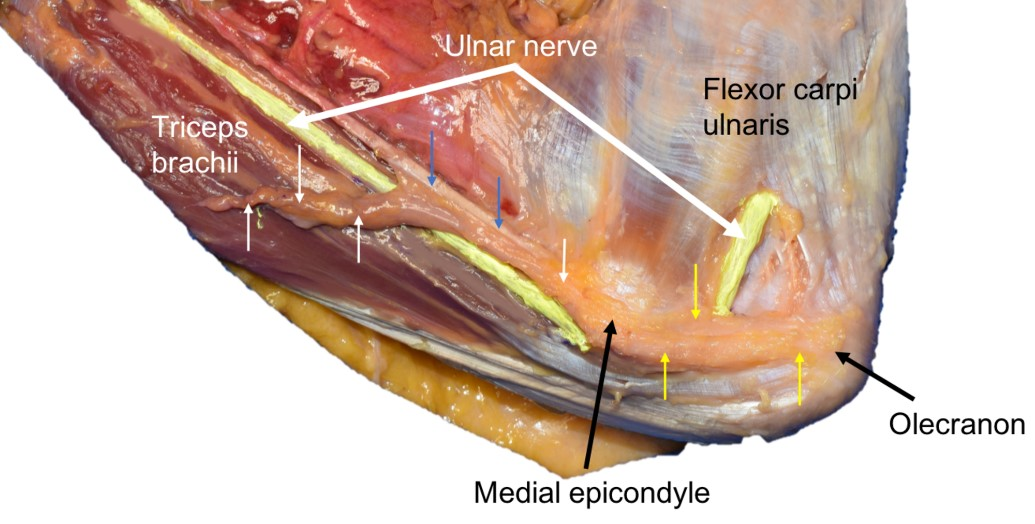

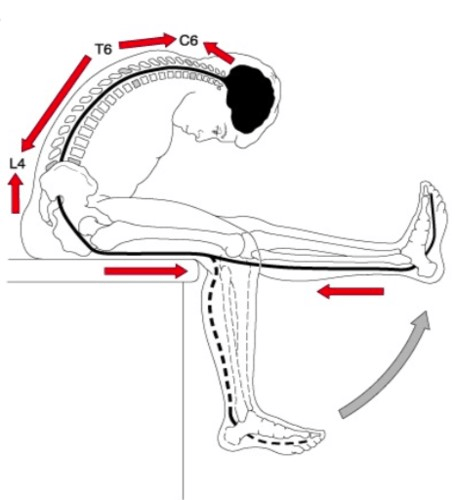

The nervous system typically handles movement, pressure, sliding, stretching, and compression very well. This happens all the time in daily life; just think about the ulnar nerve as it glides in the sulcus nervi ulnaris, experiencing stretching, compression, and sliding(1). Just tilting the head forward from a neutral to flexed position stretches the spinal cord by approximately 10%, and it stretches by 20% when moving from an extended to a flexed position. When lying on your back, a simple ankle dorsiflexion alone can move a nerve root, while a straight leg raise with dorsiflexion can create tension all the way up to the cerebellum(2). Nevertheless, sometimes nerves can be more sensitive which can result in positive neurodynamic tests.

What are neurodynamic tests, really?

Neurodynamic tests assess increased function (gain of function) (3,4), and one can say that there is increased mechanosensitivity in a positive test (5). The nerve’s sensitivity to changes in loading is tested: Do symptoms change when nerve tissue is subjected to stretching, pressure, percussion, or unloading (6)? The nerve moves most around the joint that is being moved; for example, an ankle inversion generates the most movement in the peroneal nerve on the upper side of the ankle and less movement further up the leg(2).

Why does nerve tissue become more sensitive?

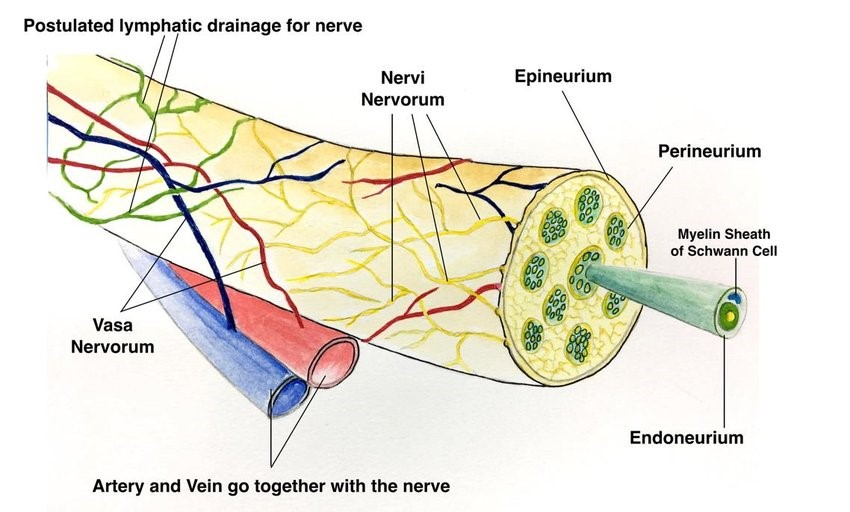

Nerve tissue can become more sensitive due to inflammation or altered sliding of the dura, nerve root, or peripheral nerve tissue (6), as in the case of disc herniation with nerve root involvement. This increased sensitivity is often due to the activation of nociceptors in the connective tissue surrounding the peripheral nerve, known as nervi nervorum (5).

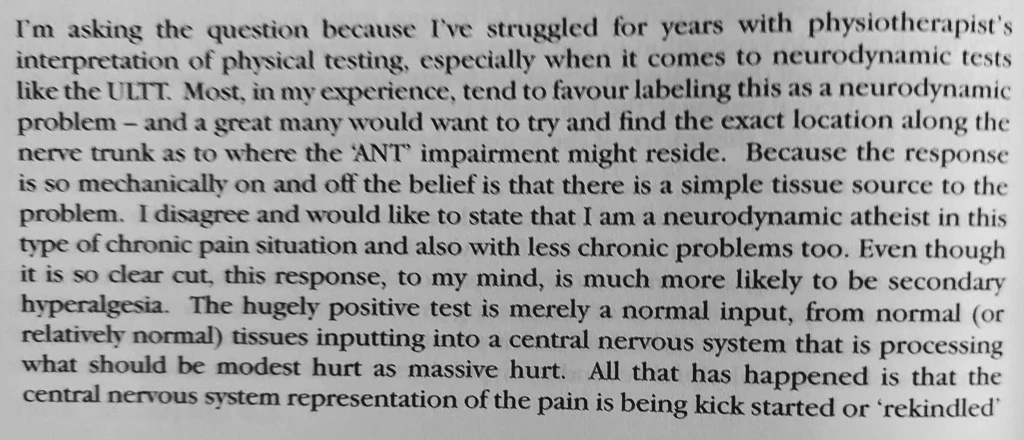

The nervous system can also be more sensitive and produce positive neurodynamic tests due to generalized hypersensitization, as shown in studies of patients with whiplash and fibromyalgia (7). Reiman (1) points out that the nervous system is highly receptive to anxiety and catastrophizing. Louis Gifford speaks about this as well. It can be easy to be deceived by a positive neurodynamic test when it is actually secondary hyperalgesia and maladaptive central processing (see more of what Louis writes below) (8). I have probably had patients myself where I have been fooled by positive neurodynamic tests and thought that there is increased mechanosensitivity due to pathology when it might actually be a larger psychosocial driver. Louis writes (8):

Of course, one should not conclude right away that “there is a positive SLR because this person is very anxious/catastrophizing, and they have a more sensitive nervous system.” If the SLR is positive, you should test strength, reflexes, and sensory function. If these are negative, THEN you might begin to consider such factors

On the other hand, there can be a positive neurodynamic test without nerve damage (radiculopathy) (7). You can have a disc herniation without pressure on the nerve, where the “chemical soup” in the area “irritates” the nerve root and produces a positive SLR.

Phew! A bit back and forth. My point is that you should not draw conclusions based on individual tests. You should conduct a thorough history and examination and be skilled in clinical reasoning, so to try as best as possible to understand what is going on with the patient.

When is a test positive?

A neurodynamic test assess whether there is increased mechanosensitivity in nerve tissue (7), NOT whether the nerve is damaged or there is conduction block (7). Some define a positive test as the reproduction of the patient’s symptoms along with reduced mobility on the affected side compared to the opposite side. Structural differentiation is also essential for a positive neurodynamic test (4,7). Differentiation means maneuvers that put nerve tissue on stretch or slack. An example of this: You perform an SLR, and the patient experiences leg and back pain. When the leg is lowered until the pain disappears, and then dorsiflexion of the ankle is performed, the pain returns. It is not always certain that the test reproduces exact symptoms. It can be valuable information and a possible positive test if there is a difference in the test from right to left side or if the symptoms are different from what is typical (2).

Patients with a greater loss of nerve function, such as diabetic neuropathy or more severe carpal tunnel syndrome, have a lower likelihood of testing positive on a neurodynamic test (7,9). A negative neurodynamic test is not enough to rule out more severe neuropathy! Nevertheless, there is a fairly high chance of detecting a low lumbar disc herniation with nerve root involvement, as a straight-leg raise test (SLR) can be positive in 92 out of 100 cases in these patients (10).

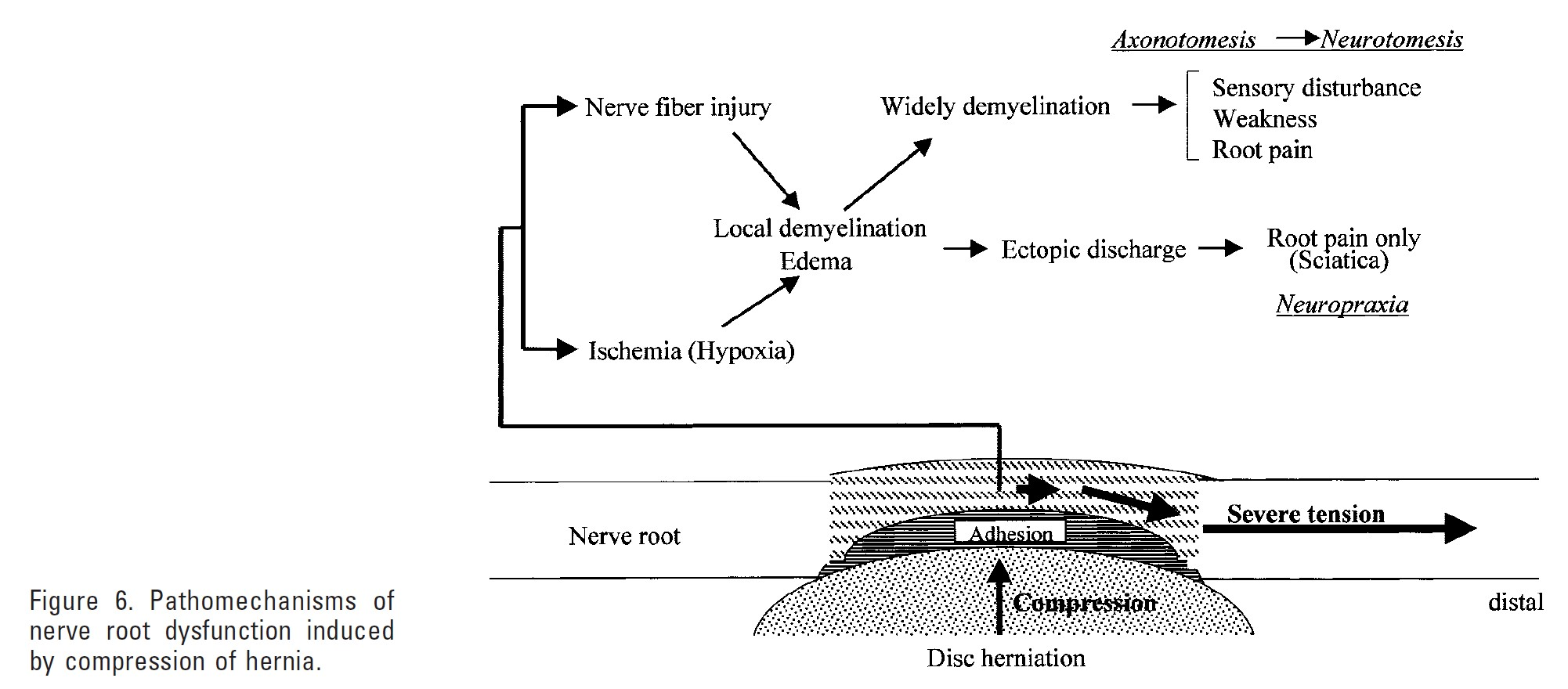

Two studies indicate that inflammation in herniation could cause adhesions between herniated material and the dura mater on the nerve root, increasing the likelihood of a positive neurodynamic test (straight leg raise and femoral nerve test) and radicular pain(11,12). Conversely, without adhesions and herniation, the nerve root might slide more freely back and forth, not necessarily resulting in the same symptoms during testing(11,12).

This inflammation in connection with disc herniation is necessary to “repair” the area and attempt to remove disc material (resorption). However, this could lead to adhesion of the dura mater on the nerve root and herniated material, which in turn puts more compression or stretch on the nerve root, potentially leading to various health effects on the nerve root and increased symptoms (11,12). One should perhaps be skeptical of the term adhesion in the physiotherapy world (e.g., friction massage for adhesions, etc.), but to me, this sounds plausible. A systematic review article found that surgery to remove fibrosis was effective for pain reduction (13), but the relationship between fibrosis and pain is inconclusive (14).

Execution

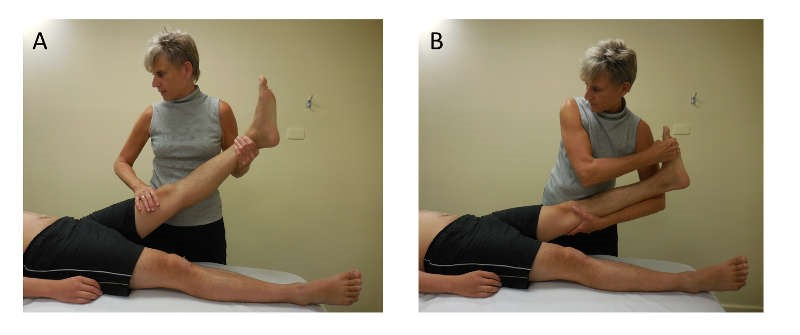

It’s essential to conduct neurodynamic tests thoroughly and not rush through them. If you perform a straight leg raise quickly, and the patient finds it painful, you shouldn’t automatically assume it’s positive and proceed to the next test. The test should be done with good technique and should ideally be standardized (at least for you!), so you can gain experience with what is a normal and abnormal response. Gifford (2) says:

If you’re a bit unsure if there’s increased mechanosensitivity in the nerve, it can be a good idea to ‘be in the test’ and ‘play around’ a bit with different variations to be completely sure of the correct interpretation. You should ask about the location of symptoms and if there are known symptoms (reproduced), look for side differences, and try to differentiate(6). Reiman (1) writes that you don’t always need to go into the pain, but you can feel an earlier stop in the movement before symptoms occur. It can be wise to go through the mobility of the hip, knee, and ankle to see if this provokes pain before a straight leg raise test, so you don’t get fooled. You should be careful not to move multiple joints at once.

Active and passive testing

Often, it can be wise for the patient to perform an active neurodynamic test before doing it passively, for example, a standing Straight Leg Raise (SLR) with support or a sitting slump test where the patient extends the knee and flexes the spine themselves. Other more general maneuvers can also put nerve tissue on stretch, which can provide an indication of increased mechanosensitivity. For instance, forward bending with extended versus slightly flexed knees, forward bending with feet on the floor versus plank under the forefoot (dorsiflexion)(2).

It can be uncomfortable, even in asymptomatic individuals

Several studies have examined how people without symptoms react to neurodynamic tests. They experience reduced joint mobility and can feel uncomfortable sensations like tingling, stabbing, or a burning feeling(15). During a slump test on asymptomatic individuals, nearly all of them (97.6%) experienced responses during full flexion of the spine, knee extension, and dorsiflexion, with a median intensity rating of 6. They felt it most in the knee, calf, or thigh. Two-thirds still experienced responses during cervical extension, but with a median intensity rating of 2. They described a sensation of stretching, tightness, and pulling(16). Studies have also been conducted on neurodynamic tests of the peroneal nerve(17) and sural nerve(18) in asymptomatic individuals.

Summary

Neurodynamic tests assess the mechanosensitivity of the nerve, NOT whether the nerve is damaged or there is a conduction block. Nerve tissue can become more sensitive due to changes in sliding or inflammation, as well as maladaptive central processing. A test is considered positive when it reproduces the patient’s symptoms, and it’s also crucial to be able to differentiate (slacken, tighten nerve tissue). Patients with significant loss of nerve function, such as diabetic neuropathy or a more severe carpal tunnel syndrome, are less likely to test positive on a nerve stretch test. Neurodynamic tests elicit responses and symptoms in individuals without complaints as well, so critical thinking is essential!

References

1. Reiman MP. Orthopedic clinical examination. 2016.

2. Gifford L. Neurodynamics. I: Pitt-Brooke, redaktør. Rehabilitation of Movement: Theoretical bases of clinical practice. London: Saunders; 1997.

3. Woolf CJ. Dissecting out mechanisms responsible for peripheral neuropathic pain: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Life Sci. 9. april 2004;74(21):2605–10.

4. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep [Internett]. 22. juli 2020 [sitert 24. september 2020];5(4). Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7382548/

5. Schmid AB, Tampin B. Section 10, Chapter 10: Spinally Referred Back and Leg Pain – International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. I: Boden SD, redaktør. Lumbar Spine Online Textbook [Internett]. 2020 [sitert 4. oktober 2020]. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.wheelessonline.com/ISSLS/section-10-chapter-10-spinally-referred-back-and-leg-pain/

6. Solberg AS, Kirkesola G. Klinisk undersøkelse av ryggen. Kristiansand: HøyskoleForlaget; 2007.

7. Schmid AB, Hailey L, Tampin B. Entrapment Neuropathies: Challenging Common Beliefs With Novel Evidence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):58–62.

8. Gifford L. Aches and pains. 2014.

9. Baselgia LT, Bennett DL, Silbiger RM, Schmid AB. Negative Neurodynamic Tests Do Not Exclude Neural Dysfunction in Patients With Entrapment Neuropathies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1. mars 2017;98(3):480–6.

10. van der Windt DA, Simons E, Riphagen II, Ammendolia C, Verhagen AP, Laslett M, mfl. Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 17. februar 2010;(2):CD007431.

11. Kobayashi S, Suzuki Y, Asai T, Yoshizawa H. Changes in nerve root motion and intraradicular blood flow during intraoperative femoral nerve stretch test. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. oktober 2003;99(3 Suppl):298–305.

12. Kobayashi S, Shizu N, Suzuki Y, Asai T, Yoshizawa H. Changes in nerve root motion and intraradicular blood flow during an intraoperative straight-leg-raising test. Spine. 1. juli 2003;28(13):1427–34.

13. Helm S, B. Racz G, Gerdesmeyer L, Justiz R, Hayek S, Kaplan E, mfl. Percutaneous and Endoscopic Adhesiolysis in Managing Low Back and Lower Extremity Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 27. januar 2016;19:E245–82.

14. el Barzouhi A, Vleggeert-Lankamp CLAM, Lycklama à Nijeholt GJ, Van der Kallen BF, van den Hout WB, Jacobs WCH, mfl. Magnetic resonance imaging in follow-up assessment of sciatica. N Engl J Med. 14. mars 2013;368(11):999–1007.

15. Lai W-H, Shih Y-F, Lin P-L, Chen W-Y, Ma H-L. Normal neurodynamic responses of the femoral slump test. Man Ther. april 2012;17(2):126–32.

16. Walsh J, Flatley M, Johnston N, Bennett K. Slump test: sensory responses in asymptomatic subjects. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(4):231–8.

17. Bueno-Gracia E, Malo-Urriés M, Borrella-Andrés S, Montaner-Cuello A, Estébanez-de-Miguel E, Fanlo-Mazas P, mfl. Neurodynamic test of the peroneal nerve: Study of the normal response in asymptomatic subjects. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. oktober 2019;43:117–21.

18. Montaner-Cuello A, Bueno-Gracia E, Bueno-Aranzabal M, Borrella-Andrés S, López-de-Celis C, Malo-Urriés M. Normal response to sural neurodynamic test in asymptomatic participants. A cross-sectional study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. desember 2020;50:102258.