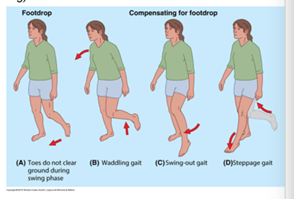

If you have a patient with signs of disc herniation and sciatica (radicular pain), you must always include muscle strength testing! If there is a large acute loss of strength, for example, a total inability to dorsiflex the ankle (drop foot), the patient should be promptly assessed in a hospital.

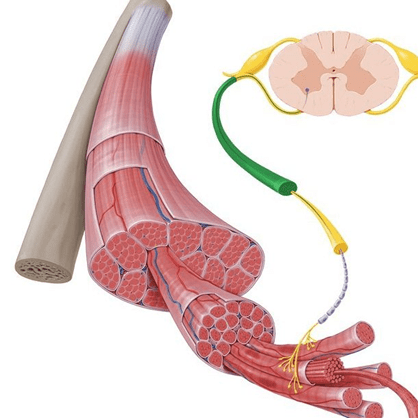

Myotome

Muscle strength tests are also called tests of myotomes when investigating for possible radiculopathy. A myotome is a group of muscles that is innervated by a single nerve root. The word comes from Greek and combines the two words “myos,” which means muscle, and “temno,” which means “to cut.” (1). A muscle can be innervated by several nerve roots, such as the quadriceps. Therefore, a muscle can have more than one myotome.

Strength tests

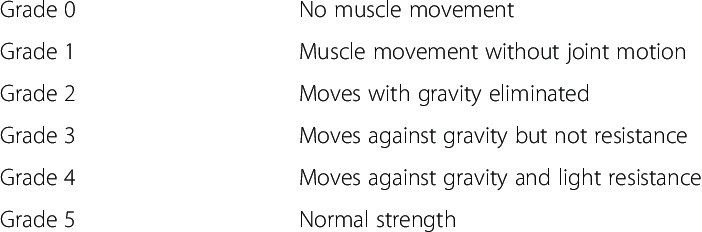

There are many ways to test strength. If you want to do a quick screening, you can have the patient walk on their toes, walk on their heels, and do a squat. In physiotherapy, manual muscle strength tests are also performed. The therapist enters the test position and asks the patient to activate the muscles maximally, holding isometrically for a few seconds, and then breaks the force (2). It is scored from 0 to 5. This scale is called the MRC scale (Medical Research Council Scale of muscle strength, also known as the Oxford scale) (3).

MRC / Oxford scale

The MRC scale is an old scale, first published in 1943 (4). Many other scales and variations of this scale have been proposed, but none have “taken over” the throne (5). This is the scale used by physiotherapists and doctors to communicate findings in disc herniation and radiculopathy (at least in Norway). It is graded from 0 to 5, where 0 is no visible muscle contraction (paralysis) and 5 is where the patient can hold against full resistance. It is important to ask the patient to exert themselves properly.

Here is a recipe for how to score:

It is important to assess the degree of strength loss as this gives an indication of further referral and possible surgery, and it is important that everyone speaks the same medical language. It is recommended to refer to the hospital for prompt evaluation (within 72 hours) for a grade 3 or lower strength loss (in Norway), but there are also divided opinions within the medical community.

What does the result mean?

There may be larger side differences due to muscle rupture, neurological conditions, paresis. Smaller side differences may be present with nerve root involvement, nerve “entrapment,” or other nerve damage (7). The test cannot be relied upon if the patient experiences pain during the test.

Other causes of weakness may be (8):

- Muscle weakness is divided into:

- Weakness caused by peripheral damage in muscles, nerves, nerve plexuses, nerve roots, or lower motor neurons in the spinal cord.

- Weakness caused by central damage in motor pathways and motor cells in the spinal cord, brainstem, or brain.

- The most common diseases that lead to muscle weakness are:

- Stroke, which often causes hemiparesis (weakness on one side of the body).

- Polyneuropathy, which can lead to peripheral paralysis, often affecting the feet the most.

- Multiple sclerosis with lesions in motor pathways can result in spastic paraparesis if it affects the spinal cord, or hemiplegia if it affects motor pathways in the brain.

- Peripheral nerve injury due to nerve compression, as seen in conditions like peroneal palsy, carpal tunnel syndrome, and radial nerve palsy, can cause weakness in the muscles innervated by the affected nerve.

- Damage/irritation of nerve roots, as in the case of herniated discs in the back or neck, can lead to muscle weakness in muscle groups corresponding to a myotome.

- Additionally, there are various rare diseases that can lead to paralysis or muscle weakness, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, myopathies, and myasthenia gravis.”

Loss of power and disc herniation

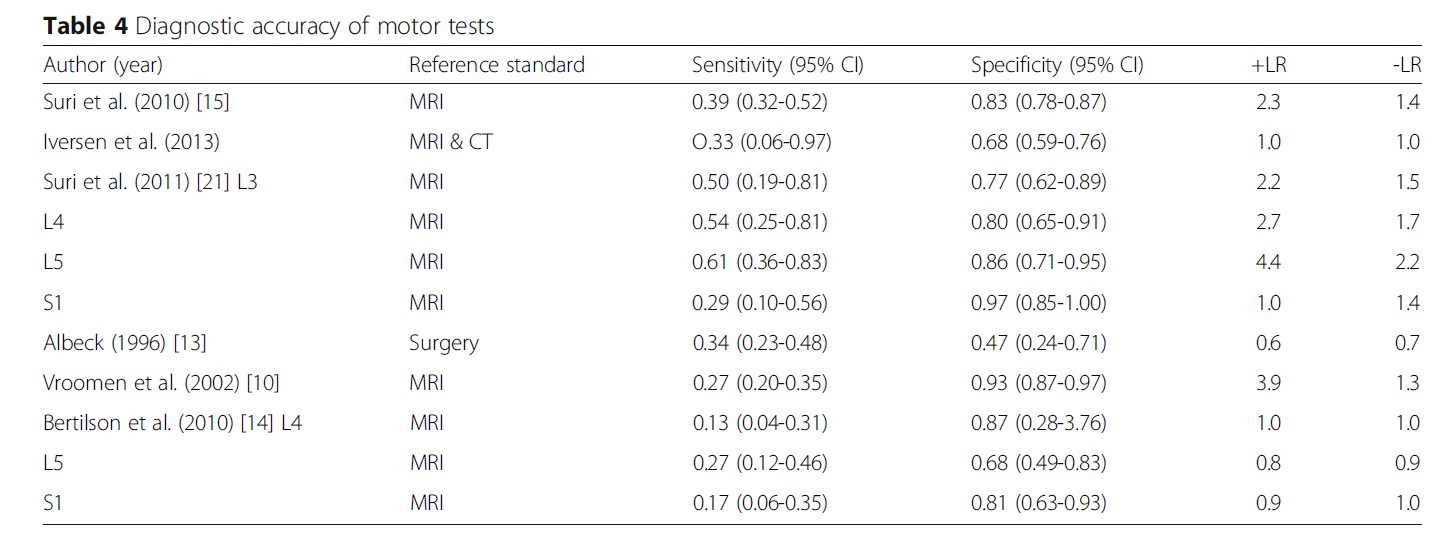

Muscle strength testing alone cannot diagnose a lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. A systematic examination with meta-analysis found that the sensitivity for diagnosing disc herniation with muscle strength testing was 0.22 and 0.44, and a specificity of 0.79 and 0.62 (compared to MRI and surgery) (9).

One of the newer systematic reviews shows varying sensitivity and specificity in the included studies (10).

It makes sense that one cannot diagnose a disc herniation and radiculopathy solely based on strength testing. You would of course be certain of a diagnosis if you includes testing of reflexes, sensitivity, and neurodynamics. In a test battery, the specificity increases to 0.90, 0.83, and 0.94 to diagnose disc herniation and radiculopathy L4, L5, and S1 (11).

Is there a standard myotome chart?

Just as there is a dermatome chart for testing sensitivity, one can think of a myotome chart for strength testing. If a muscle is weak, which nerve root is affected? Typically, one learns a certain rule at the university, such as quadriceps L4, tibialis anterior L5, and triceps surae S1. However, digging deeper into the literature, it is not so black and white.

It appears that there is not a complete consensus on which muscles to test, for example, the medical studies at UiO use the following recipe:

- Hip flexion L2/L3

- Knee extension L4

- Ankle dorsiflexion L5

- Plantarflexion S1

I have used the following chart for performing neurologically tests based on Solberg (2). This chart is a little more nuanced, where one can see that several muscles have an overlap of which nerve roots they are innervated by.

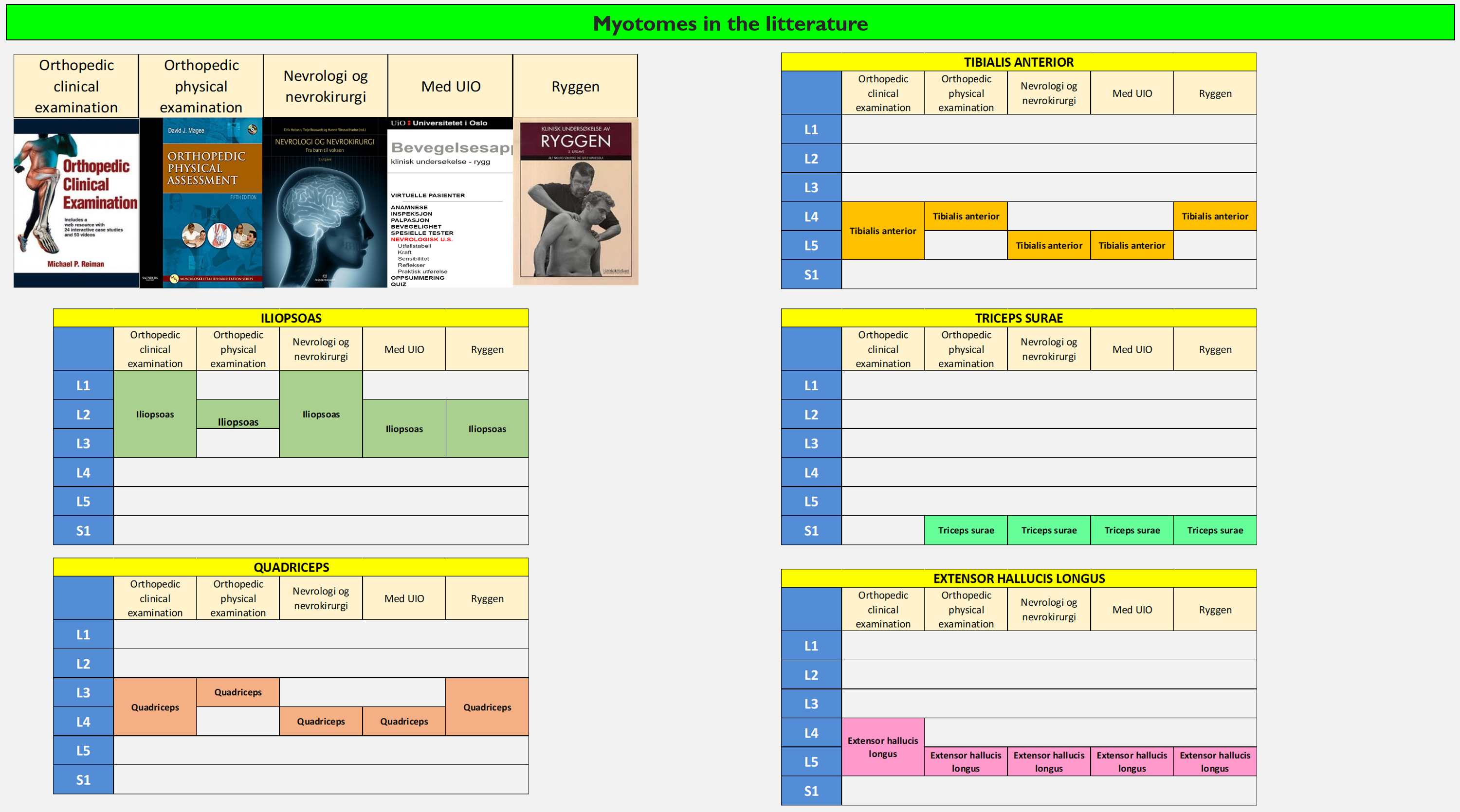

I have also done some research on my own, and looked at what is stated in some books I have on my bookshelf to see if they match:

The books are quite consistent on the m. extensor hallucis and triceps surae, but when it comes to the other muscles, they are a bit divided. Why is that? Can’t they agree? Does it matter?

I had a patient with grade 2 paresis. I referred him for an MRI and received a quick response. I called the hospital and asked if they would assess the patient. I was told that they would not see him because the nerve root involvement on the MRI did not match the standard myotome chart. I was quite sure that the disc herniation was the cause of his weakness, as SLR/Lasegue and other tests were positive, but it did not follow the “textbook myotome chart.” So it matters!

Myotome map 2.0

How can one determine which nerve root goes to which muscle? Here are some studies that have looked at this.

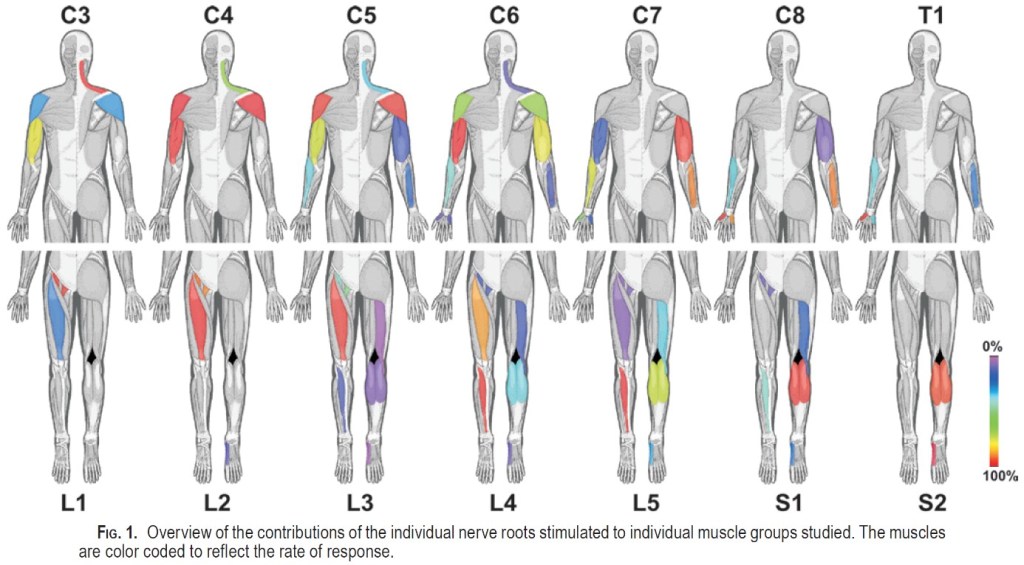

One of the most comprehensive studies was done by Schirmer et al. (2011) (12). They performed 1589 stimulations of nerve roots in patients who were to undergo surgery, and then recorded electrical activity in the muscles.

They found that in many cases there was a broader range of nerve roots that innervate muscles (12). For example, they found that a large part of the innervation of the quadriceps came from L2, L3 and L4, but also some from L1. See the diagram for details.

If one were to create a diagram, it would look like this:

One downside of this study is that they did not include gluteal muscles, peroneal muscles, and extensor hallucis longus. It is a bit surprising that there is little response in the biceps femoris. Perhaps they would have seen more had they included the semimembranosus and semitendinosus? An article mentions that there is some disagreement about whether the hamstring muscles are affected by S1 radiculopathy. It is thought that the loss of strength is greatest/most visible distally to the knee in S1 radiculopathy (13).

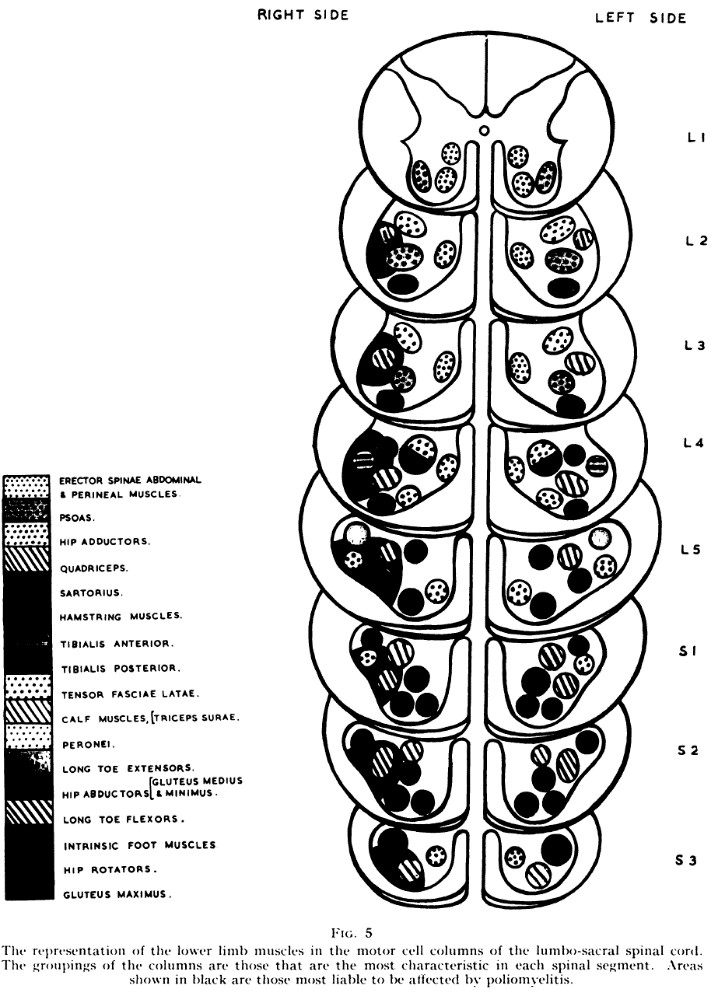

The results of this study also agree well with the results of an old study that examined what kind of neurological damage polio patients suffered (14). The polio virus can attack and destroy the motor neurons in the spinal cord (15). They found that some muscles had long “motor cell columns,” meaning they stretched further axially, e.g. hip flexors and adductors. When the polio attacked nerve roots that innervated these muscles, they did not become paralyzed. Muscles that were innervated by short motor cell columns were more likely to be paralyzed, e.g. tibialis anterior, tibialis posterior, peroneal muscles, and the long muscles of the toes (14).

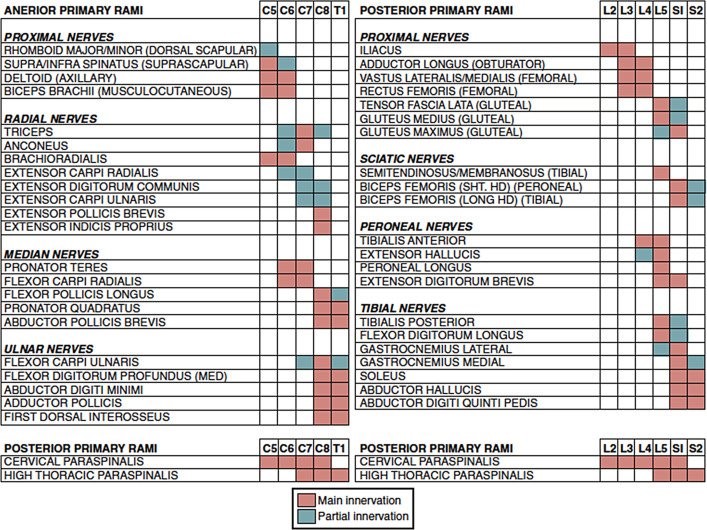

Another very good article has looked at electrophysiological studies of patients with radiculopathy (13). This is the consensus of the authors:

This is not actually very different from Schimer’s study (12). If you look at the different studies, a pattern emerges. Muscles can be innervated by several nerve roots, and there are probably individual normal variations.

Summary of sources

In lumbar disc herniation, it is most relevant to test L5 and S1, as 95% of lumbar herniations occur at the two lower levels (16).

It is difficult (impossible?) to differentiate nerve root involvement of L2, L3, and L4 when testing myotomes, as there is such a large overlap. The muscles are also proximal and they reinnervate faster (13). If you look at the sources in some books, it is incorrect to say that quadriceps is a test of only the L4 nerve root. I would say that quadriceps tests the L2-4 nerve roots.

L5 radiculopathy is the most common in lumbar disc herniation (13). It is worth noting that tibialis anterior can be weak in both L4 and L5 nerve root involvement. In some of the books, it only says L4, which is incorrect based on the studies here. In the Schirmer study, tibialis anterior is the muscle that reacts the most to both L4 and L5 nerve root stimulation (12).

S1 radiculopathy is the second most common nerve root affected in lumbar disc herniation. Triceps surae (gastrocnemius and soleus) is a good muscle group to test for this, according to Schirmer (12). The textbooks agree on this.

Confused?

It can be confusing when sources say different things. The point here is that you cannot necessarily put two lines under the answer above as to which nerve root is affected when you test strength. PROBABLY, you can say which nerve root is affected, but there is also a possibility that it may be another nerve root. You can increase the likelihood of localizing the nerve root by including more muscles in your test battery, for example, like Solberg. One study suggests that an examination is positive if there is weakness in two or more muscles innervated by the same root. It is even better if it is the SAME nerve root but DIFFERENT peripheral nerve (17). E.g.:

- test of m. tibialis anterior innervated by n. peroneus communis and L4 and L5 nerve roots

- vs.

- test of m. tibialis posterior innervated by n. tibialis and L5 and S1 nerve roots

This summarizes it well regarding myotome mapping (13):

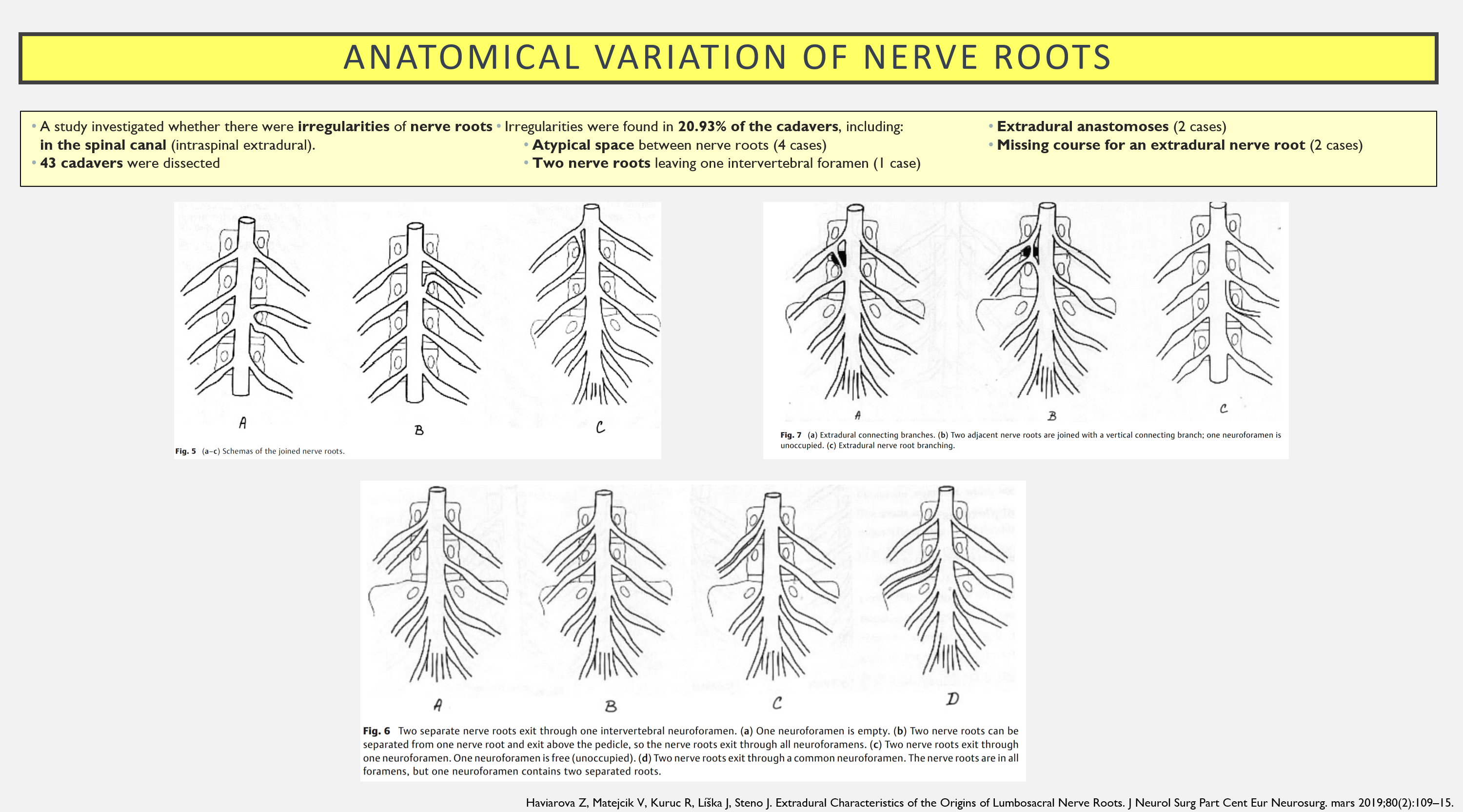

We know that there are anatomical normal variations in the human body, that also includes nerve roots. Take a look at this study f.ex.:

Risk factors for significant muscle weakness?

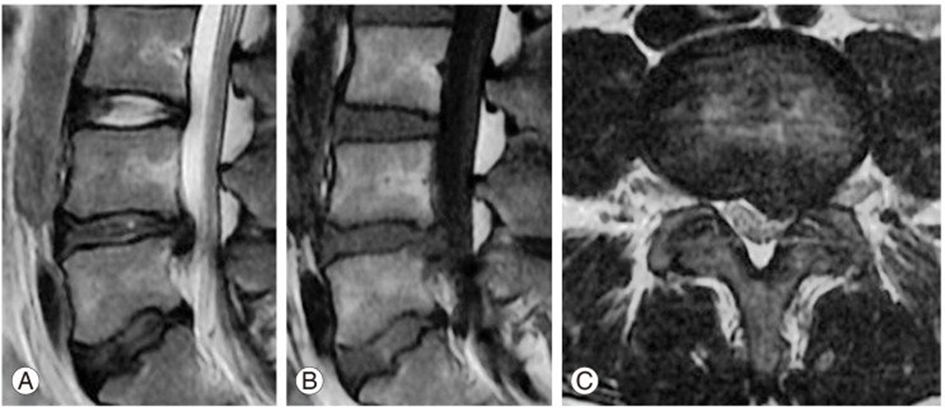

A study (18) examined risk factors for developing foot drop in connection with lumbar disc herniation and radiculopathy. This was a retrospective study involving 236 patients, with 52 patients developing foot drop. Factors that can influence and increase the likelihood of developing foot drop include:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Acute or acute-on-chronic episode

- Disc herniation in the recess or intervertebral foramen

- Disc calcification (?)

- The disc occupying more than 50% of the space in the canal

- Smaller spinal canal (a 1 mm increase in anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal reduced the risk of foot drop by 51.8% (p<0.05))

How to test?

The most important thing is to learn a way to test and standardize this. It can be useful to learn to do this while sitting, lying on your back, and in a more functional position (standing on tiptoes, heels, squats). I use the recipe in the Solberg book. It can be difficult to detect muscle weakness in strong muscles, such as the quadriceps. A study found that there had to be at least a 50% loss of strength in the quadriceps for this to be detected on a manual strength test. They found that “sit-to-stand” together with neurodynamic testing for the femoral nerve was good for detecting radiculopathy of the L2-4 nerve root, with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 90% (19).

Triceps surae is difficult to evaluate while sitting or lying down, as it is a strong muscle with a large internal moment arm. I ask the patient to perform 10 quick heel raises on the left and right, all the way up and all the way down. This makes it easier to detect differences in strength.

What about realiability?

There is probably a lot that can be said about the reliability of strength tests and the MRC scale. It depends on who is testing, the starting position, how much you push the patient to exert themselves, the tester’s experience, whether the patient has pain, etc. However, I believe that this is the best and quickest way to evaluate any loss of strength. If you have to bring out a dynamometer and try to quantify it, it can quickly take a long time and it can also be difficult to standardize. Therefore, I believe that the best approach is to test a lot of strength manually and build a large reference material. This way, you can more easily detect what is abnormal.

Summary

Strength tests must always be included if you suspect disc herniation and radiculopathy. In the event of significant acute loss of strength, the patient should be evaluated in the hospital. Strength is graded from 0-5. You cannot draw final conclusions about which nerve root is affected based on which muscle is weak. It is advisable to practice a way of doing it and become good at it, so that you can detect any abnormal findings.

References

- Holck P. myotomer. I: Store medisinske leksikon [Internet]. 2021 [cited February 11, 2022]. Available from: http://sml.snl.no/myotomer

- Solberg AS, Kirkesola G. Klinisk undersøkelse av ryggen. Kristiansand: HøyskoleForlaget; 2007.

- Conable KM, Rosner AL. A narrative review of manual muscle testing and implications for muscle testing research. J Chiropr Med. September 2011; 10(3):157–65.

- Compston A. Aids to the investigation of peripheral nerve injuries. Medical Research Council: Nerve Injuries Research Committee. His Majesty’s Stationery Office: 1942; pp. 48 (iii) and 74 figures and 7 diagrams; with aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. By Michael O’Brien for the Guarantors of Brain. Saunders Elsevier: 2010; pp. [8] 64 and 94 Figures. Brain J Neurol. October 2010;133(10):2838–44.

- O’Neill S, Jaszczak SLT, Steffensen AKS, Debrabant B. Using 4+ to grade near-normal muscle strength does not improve agreement. Chiropr Man Ther [Internet]. October 10, 2017 [cited November 14, 2020]; 25. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5633899/

- Ciesla N, Dinglas V, Fan E, Kho M, Kuramoto J, Needham D. Manual Muscle Testing: A Method of Measuring Extremity Muscle Strength Applied to Critically Ill Patients. J Vis Exp JoVE [Internet]. April 12, 2011 [cited March 20, 2021]; (50). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3169254/

- Solberg AS. Den essensielle undersøkelsen [Internet]. 2015 [cited February 12, 2022]. Available from: https://www.fysioterapeuten.no/den-essensielle-undersokelsen/123133

- Motilitet [Internet]. [cited February 13, 2022]. Available from: https://studmed.uio.no/elaring/fag/nevrologi/motilitet.html

- Al Nezari NH, Schneiders AG, Hendrick PA. Neurological examination of the peripheral nervous system to diagnose lumbar spinal disc herniation with suspected radiculopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. June 2013; 13(6):657–74.

- Tawa N, Rhoda A, Diener I. Accuracy of clinical neurological examination in diagnosing lumbo-sacral radiculopathy: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 23, 2017;18(1):93.

- Petersen T, Laslett M, Juhl C. Clinical classification in low back pain: best-evidence diagnostic rules based on systematic reviews. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 12, 2017;18(1):188.

- Schirmer CM, Shils JL, Arle JE, Cosgrove GR, Dempsey PK, Tarlov E, et al. Heuristic map of myotomal innervation in humans using direct intraoperative nerve root stimulation. J Neurosurg Spine. July 2011;15(1):64-70.

- Wilbourn AJ, Aminoff MJ. AAEM minimonograph 32: the electrodiagnostic examination in patients with radiculopathies. American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Muscle Nerve. December 1998;21(12):1612-31.

- Sharrard WJ. The distribution of permanent paralysis in the lower limb in poliomyelitis; a clinical and pathological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. November 1955;37-B(4):540-58.

- Gjerstad L, Myrvang B. Polio. In: Store medisinske leksikon [Internet]. 2021 [cited February 13, 2022]. Available at: http://sml.snl.no/polio

- Jordan J, Konstantinou K, O’Dowd J. Herniated lumbar disc. BMJ Clin Evid. March 26, 2009;2009.

- Lauder TD, Dillingham TR, Huston CW, Chang AS, Belandres PV. Lumbosacral radiculopathy screen. Optimizing the number of muscles studies. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. December 1994;73(6):394-402.

- Ma J, He Y, Wang A, Wang W, Xi Y, Yu J, et al. Risk Factors Analysis for Foot Drop Associated with Lumbar Disc Herniation: An Analysis of 236 Patients. World Neurosurg. February 1, 2018;110:e1017-24.

- Suri P, Rainville J, Katz JN, Jouve C, Hartigan C, Limke J, et al. The accuracy of the physical examination for the diagnosis of midlumbar and low lumbar nerve root impingement. Spine. January 1, 2011;36(1):63-73.