NB: This blog is mainly written for the Norwegian Health Care system. There are probably other ways of doing it in other countries.

It is three o’clock on a Friday, and you are prepared to leave work and enjoy your weekend. However, you have one last patient: a 35-year-old presenting with back and leg pain. Over the past two days, the patient has experienced severe tingling in the leg and a noticeable decrease in leg strength. During a run yesterday, he was unable to push off effectively with his calf. When tested, he can perform only two poor repetitions of a single-leg heel raise on the left leg, compared to twenty on the right. Should this patient be referred to the hospital? Should an MRI be ordered? Or is it appropriate to wait?

Who Should Be Referred Immediately to the Hospital (Emergency)?

For patients with disc herniation, two primary criteria necessitate an urgent hospital referral for a rapid MRI and surgical evaluation:

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Significant or progressive paresis/paralysis

Some patients may have severe radicular pain that is challenging to manage, but hospitalization is often avoided since these pains are usually temporary, and early spinal surgery based on pain alone is discouraged.

1. Cauda equina-syndrome

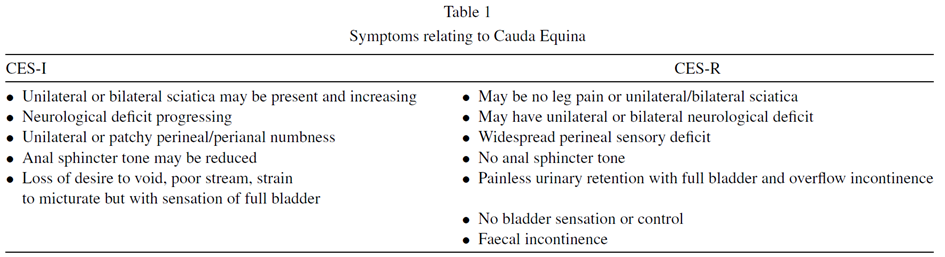

Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES) is a rare condition, affecting only two percent of those with lumbar disc herniation. Symptoms may include: (1).

There is no definitive checklist for how CES develops. A good approach involves collaborating with the patient to create a timeline of symptom onset and progression. Important questions include those about sciatica, bladder function (remember, urinary retention means being unable to urinate), bowel function, saddle area sensation, and sexual function (2). It’s advisable to consult the International Framework for Red Flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies (2) or Tom Jesson’s infographic or book on CES. If CES is suspected, an urgent hospital referral for MRI and surgical assessment is necessary. The hospital will often perform a bladder ultrasound to check for urinary retention. If you believe the patient is at risk for developing CES later, establish a safety net by informing them of symptoms to watch for and appropriate actions to take (2).

2. Paresis/Paralysis

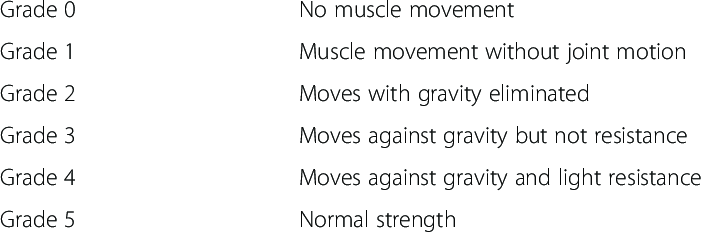

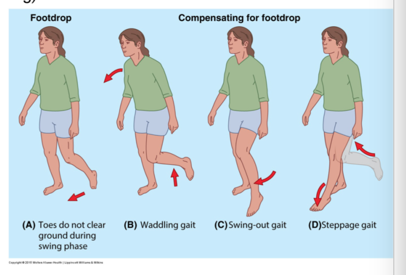

What constitutes a significant enough loss of power to warrant serious consideration? The short and simple answer is that a strength loss graded at 3 or lower should be evaluated promptly. Some suggest >3. This often refers to foot drop, where the patient cannot dorsiflex the ankle against gravity, or inability to perform a single-leg heel raise on one leg.

Of course, this concerns patients with newly developed muscle weakness, not those who have had a foot drop for several years. And how quickly should one be admitted and evaluated? A neurologist I spoke with said that the patient should be admitted within 72 hours of developing muscle weakness of greater significance. One can question how realistic this is. Many patients do not know what is happening, and often it can take longer before they receive medical help. Other hospitals say preferably within a week. A significant muscle weakness, especially if progressive, can indicate surgery. Of course, the earlier the better when it comes to nerve tissue. If it takes too long, the hospital is less eager to admit the patient – they say it has been too long and there is nothing they can do. Therefore, it is important to find out how the symptoms progressed, especially the muscle weakness! Did it start two days ago, or two weeks ago?

Interestingly, larger herniations tend to resorb more, and greater reduction in size over time correlates with better prognosis. Muscle weakness combined with radicular pain often predicts a better outcome than radicular pain alone (3). Sometimes, patients referred for significant weakness do not undergo surgery but recover full strength months later. Conversely, delayed evaluations can result in permanent foot drop.

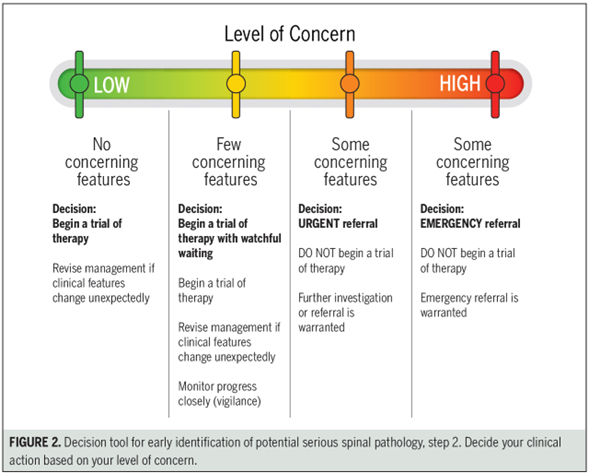

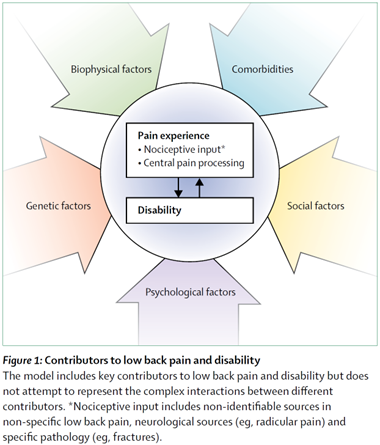

Other Red Flags

Other red flags associated with the lumbar spine include fractures, metastases, tumors, infections, and more. Refer to Finucane et al. (2) for a comprehensive list. It’s important to note that red flags lack validity and specificity; 80% of individuals with low back pain have at least one red flag, while 64% of those with malignancy show none (4,5). Therefore, a thorough overall assessment is necessary. The following figure can be used as a tool for evaluation:

How to Admit a Patient to the Hospital

Again, this is for Norway. I am not sure how you would do it in other countries.

Let’s say you have a patient with a newly onset drop foot. How do you proceed with line of action? usually tell the patient that I want to discuss their case with a hospital doctor to determine the urgency of further assessment. They wait outside the office while I make the call. Starting with the on-call doctor at the hospital is advisable rather than sending the patient directly to the emergency department. Present the case, especially your findings, express your concerns, and ask if the patient should be admitted. If the on-call doctor recommends admission, finish your notes, print them, inform the patient of the next steps, and provide them with your documentation (in case it’s not transferred electronically). Follow up with a call to the patient later to check on their status.

It’s better to make one too many phone calls to the hospital than one too few. Most doctors are willing to discuss patient cases, but ensure you are well-prepared know what you are talking about.

Gray areas

For patients with grade 3 muscle weakness or worse, after consulting with the on-call doctor who decides not to admit, consider the following options:

- Monitor the patient, ensuring they contact you immediately if symptoms worsen.

- Arrange an MRI through the private health care system, which can be done quite quick

- Arrange an MRI through the public health care system, which will take longer

Discuss these options with the patient to determine the best course of action. Sometimes early MRI can be beneficial, particularly if symptoms are worsening. This can make you fit with more information when discussing the case with a medical specialist. However, it’s essential to balance this against potential iatrogenic and nocebo effects (6).

Early MRI and Surgical Assessment

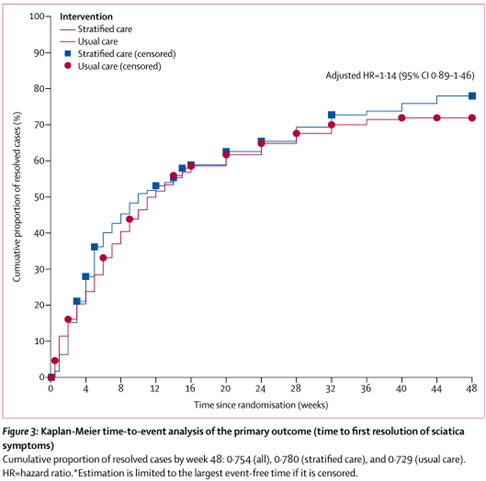

Is there a better prognosis with early MRI and surgical evaluation? Rapid surgery for significant weakness is crucial to prevent nerve damage. However, studies like those by Konstantinou et al. (7) show no significant difference between early MRI/surgical assessment and conservative management for this patient group, excluding those with significant weakness or CES.

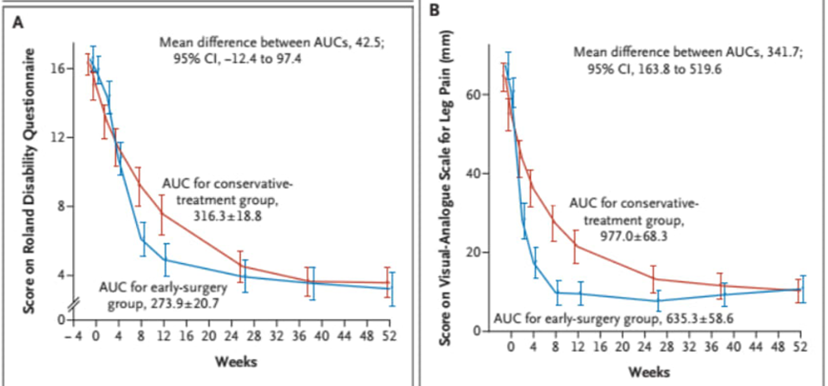

Similar findings are observed in studies comparing early surgery to a “wait and see” approach. For instance, patients with radicular pain for 6-12 weeks who underwent early surgery (blue) improved faster than those receiving conservative treatment (red), but there was no difference after a year (8). Such studies often suffer from cross-over effects, where patients initially randomized to conservative treatment eventually undergo surgery due to severe symptoms (40 % in this case).

The Role of Clinician Expertise

These findings tell me loud and clear that nothing beats a good subjective, examination and proper communication with the patient. For example, with positive straight leg raise (SLR) and crossed SLR tests, mild weakness in ankle dorsiflexion (grade 4), and reduced sensation over the big toe, you can confidently diagnose lumbar disc herniation with a L5 nerve root involvement. Communicate this clearly to the patient, reassure them, and follow up. Immediate MRI is not always necessary unless symptoms progress.

Guidelines

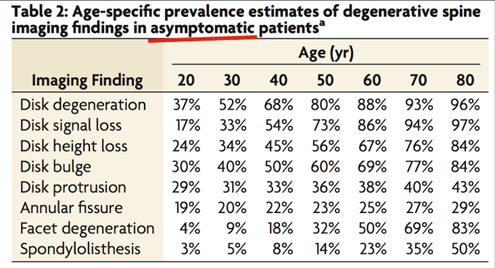

Norwegian guidelines (9,10) recommend against MRI for nonspecific low back pain. This is logical since MRI findings often do not change management and can sometimes exacerbate issues. Many people have incidental MRI findings without significant clinical relevance (11). Initial MRI is also not recommended for radiculopathy without red flags. In England, similar recommendations are made. Danish guidelines suggest careful consideration of early MRI referrals.

Key question

A useful question to determine the need for MRI is:

Will an MRI potentially change the treatment? Yes or no?

In most cases, the answer is no. This is a good educational question so that the patient understands why it is not necessary. If there is still doubt, it might be possible to identify why the patient still wants an MRI. Maybe they are anxious about a specific disease or condition. Then ask follow-up questions like “What do you think is wrong?”, “Where do you think this pain comes from?”, “What are you most worried about right now?” If these concerns come to light, it is easier to reassure the patient.

Can It Be Negative to Do an MRI of the Lower Back?

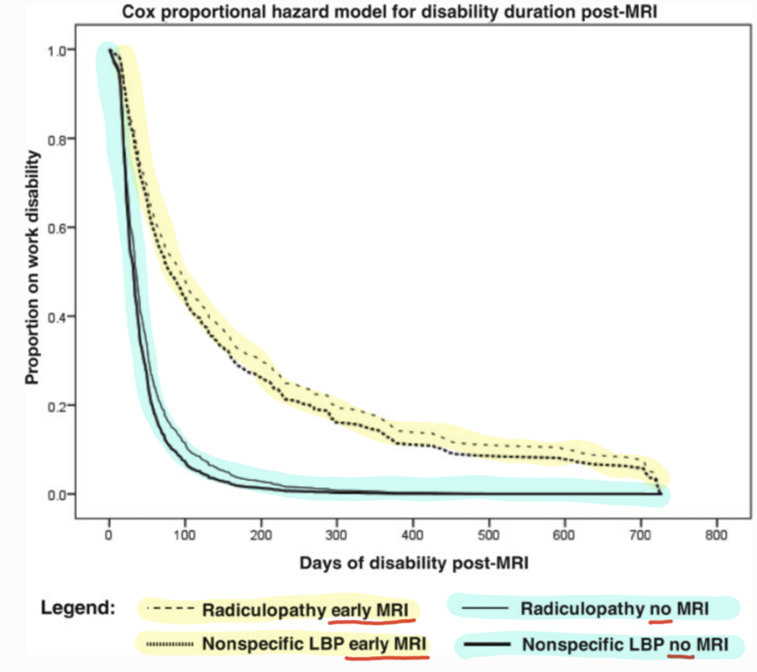

A well-known Norwegian radiologist suggests that we should “ban MRI of the lower back.” Maybe he is right? Because we have studies showing that one can experience more issues after an MRI. Plus, it is very costly for the individual and society (6, 12). The study by Webster et al. illustrates this well (6). They looked at workers who had acute lower back pain, with and without radiculopathy. They found that those who had early MRIs fared worse compared to those who did not have MRIs at all.

Webster (6) states something as strong as:

“Early MRI without indication has a strong iatrogenic effect in acute LBP, regardless of radiculopathy status. Providers and patients should be made aware that when early MRI is not indicated, it provides no benefits, and worse outcomes are likely.”

Another problem is how MRI findings are interpreted and explained. According to one study, two-thirds of MRI findings are misinterpreted, leading to a cascade of unnecessary referrals. This delays appropriate treatment (which in most cases is conservative treatment). They found that 1 person is mismanaged for every 1-2 people who receive an MRI scan. According to this study, only 5% of MRIs were indicated (12). To further complicate matters, there is also a large difference in how an MRI image is interpreted by a radiologist. For example, the famous study where a patient with back and leg pain went and had MRIs at ten different locations. No findings were reported by all the radiologists (13). There was thus little consensus.

As we know, there are incredibly many people who have changes in their spine on MRI, even those WITHOUT pain (14). Does it matter to these patients when the doctor sends the MRI report electronically without any explanation? Yes, I think so! If you start googling “disk degeneration,” you will probably come across a lot of misleading shit posts from poor sources.

Studies show that receiving information in medical language reduces self-perceived health, increases anxiety, increases perceived severity, and increases the likelihood of invasive measures (12). Due to the MRI scan, you feel worse than before you did it! This is what is called an iatrogenic effect, or also the nocebo effect. Receiving a medical label can increase fear of movement, reduce belief in physiotherapy, and increase belief in surgery – all when we’re actually just talking about common back pain (12). Patients also have an exaggerated belief in MRIs. Half of the patients who have been followed up in a clinic for cervical radiculopathy would undergo surgery based on MRI findings, even though they had no symptoms (15). Similar findings have also been seen for the lower back (16). When the patient then comes to you as a therapist later down the road, having gotten many medical labels, it is more difficult to get the patient to change their beliefs and understanding of lower back pain (12).

There has even been a randomized controlled trial (RCT) on patients who receive two different explanations of the MRI findings for their lower back. One group received a detailed medical report, while the other received a message that it was normal changes. Six weeks later, the first group, those who received the medical report, had a significantly more negative perception of their condition and significantly less improvement in pain and function (17).

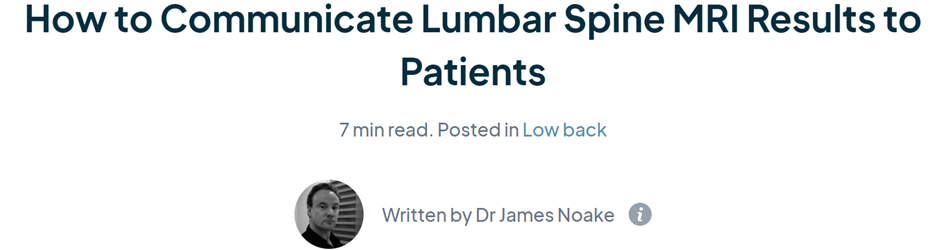

I recommend reading James Noake’s article on how to explain MRI findings to patients.

Cognitive and Affective Reassurance

A small tip is to be aware of cognitive and affective reassurance. An example of affective reassurance is when the patient is anxious, and you say, “It’s going to be okay.” Cognitive reassurance is when you give the patient objective and neutral information about their condition, and cognitive reassurance has been shown to be better in the short and long term (18). You should therefore try to inform the patient as well as possible about etiology, prognosis, and treatment, so that the patient understands what is going on. Like James talks about in his article.

Ignoring the Psychosocial Factors

An MRI scan is viewed through the lens of the pathoanatomical model. That is, one tries to “find something wrong” in the body. When this is the focus, one might overlook psychosocial factors that are more important. There are several studies showing that psychosocial factors can have more impact on functional impairment and the development of chronic pain compared to biomedical or biomechanical factors (19-22). We know that the presence of depression, anxiety, catastrophizing, and low self-efficacy increases the likelihood of functional impairment with lower back pain (11). If you have depression, sleep 3 hours a night, are going through a breakup, do not exercise, and are lonely – then this is probably more important than a small protrusion of the L5 disc. For many clinicians, it is probably much easier to talk about pathoanatomy, but you make a big mistake as a clinician if you never ask the patient how they’re actually doing and what is going on in their life.

Case – revisited

So what should we say to our patient who clearly has a disc herniation, likely an S1 nerve root involvement, and still got a grade 4 strength in his calf? I would have a thorough conversation about what this is, prognosis, what I can do, and what he can do. Then I would probably follow up with the patient weekly but ask him to monitor and contact me or an emergency room/hospital if there is significant worsening – for example, if he cannot walk on this toes. I would probably not see much need for an MRI initially, but one could consider it if there is no improvement after a few weeks or if there is worsening.

Summary

You should refer for urgent care for cauda equina syndrome and significant/progressive muscle weakness. Be aware of other red flags. Call the on-call doctor to consult before potentially admitting the patient. For those who do not need immediate help, it is uncertain how much benefit there is in getting an early MRI and early surgical evaluation. Much of the literature suggests avoiding early MRI and perhaps avoiding MRI altogether.

References

1. Greenhalgh S, Truman C, Webster V, Selfe J. An Investigation into the Patient Experience of Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES). Physiotherapy Practice and Research. 2015 Jan 1;36:23–31.

2. Finucane LM, Downie A, Mercer C, Greenhalgh SM, Boissonnault WG, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, et al. International Framework for Red Flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Jul;50(7):350–72.

3. Jesson T. Understanding sciatica. 2023.

4. Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, et al. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Oct;60(10):3072–80.

5. Premkumar A, Godfrey W, Gottschalk MB, Boden SD. Red Flags for Low Back Pain Are Not Always Really Red: A Prospective Evaluation of the Clinical Utility of Commonly Used Screening Questions for Low Back Pain. JBJS. 2018 Mar 7;100(5):368.

6. Webster BS, Bauer AZ, Choi Y, Cifuentes M, Pransky GS. Iatrogenic Consequences of Early Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Acute, Work-Related, Disabling Low Back Pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 Oct 15;38(22):1939–46.

7. Konstantinou K, Lewis M, Dunn KM, Ogollah R, Artus M, Hill JC, et al. Stratified care versus usual care for management of patients presenting with sciatica in primary care (SCOPiC): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2020 Jul 1;2(7):e401–11.

8. Peul WC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, Thomeer RTWM, Koes BW. Prolonged conservative care versus early surgery in patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008 Jun 14;336(7657):1355–8.

9. Sharma, Bjørnarå, Robinson, Hjemly, Hammerlund, Myrseth, et al. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for bildediagnostikk ved ikke-traumatiske muskel- og skjelettlidelser [Internet]. Helsedirektoratet; 2014 [cited 2018 Jun 8]. Available from: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/662/Bildediagnostikk-ved-ikke-traumatiske-muskell-og-skjelettlidelser-IS-1899.pdf

10. Lærum E, Brox JI, Storheim K. Nasjonale kliniske retningslinjer. Korsryggsmerter – med og uten nerverotaffeksjon. FORMI, Formidlingsenheten for muskel- og skjelettlidelser/Sosial- og helsedirektoratet. 2007;

11. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018 09;391(10137):2356–67.

12. Sajid IM, Parkunan A, Frost K. Unintended consequences: quantifying the benefits, iatrogenic harms and downstream cascade costs of musculoskeletal MRI in UK primary care. BMJ Open Qual. 2021 Jul 1;10(3):e001287.

13. Herzog R, Elgort DR, Flanders AE, Moley PJ. Variability in diagnostic error rates of 10 MRI centers performing lumbar spine MRI examinations on the same patient within a 3-week period. The Spine Journal. 2017 Apr 1;17(4):554–61.

14. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, et al. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015 Apr;36(4):811–6.

15. Weber C, Behbahani M, Baardsen R, Lehmberg J, Meyer B, Shiban E. Patients’ beliefs about diagnosis and treatment of cervical spondylosis with radiculopathy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017 Dec;159(12):2379–84.

16. Franz EW, Bentley JN, Yee PPS, Chang KWC, Kendall-Thomas J, Park P, et al. Patient misconceptions concerning lumbar spondylosis diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2015 May 1;22(5):496–502.

17. Rajasekaran S, Dilip Chand Raja S, Pushpa BT, Ananda KB, Ajoy Prasad S, Rishi MK. The catastrophization effects of an MRI report on the patient and surgeon and the benefits of ‘clinical reporting’: results from an RCT and blinded trials. Eur Spine J. 2021 Jul 1;30(7):2069–81.

18. Pincus T, Holt N, Vogel S, Underwood M, Savage R, Walsh DA, et al. Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Pain. 2013 Nov;154(11):2407–16.

19. Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller JL, Carragee JM. Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J. 2005 Feb;5(1):24–35.

20. Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009 Feb 7;373(9662):463–72.

21. Chou R, Shekelle P. Will this patient develop persistent disabling low back pain? JAMA. 2010 Apr 7;303(13):1295–302.

22. Picavet HSJ, Vlaeyen JWS, Schouten JSAG. Pain catastrophizing and kinesiophobia: predictors of chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Dec 1;156(11):1028–34.