A disc herniation can be very painful, especially if you also have sciatica. On the other hand, it is well-known in the physiotherapy community that one can have a herniation without pain. When is a disc herniation painful? There is no black-and-white answer, and when it comes to the spine, there are no rules without exceptions. In this post, I will try to summarize what may be relevant in determining whether a herniation can cause symptoms. If you want to delve even deeper, I recommend Tom Jesson’s book, which can be found here.

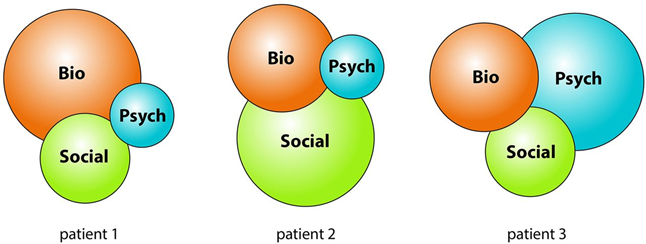

Not just bio

As I have mentioned before, there can be an overemphasis in these texts on the biomedical aspect. One must, of course, consider the individual patient and explore psychosocial factors. Radicular pain can be very painful and limiting for the patient’s life. Interestingly, it is uncertain/disputed whether psychosocial factors affect the prognosis of conservative treatment for patients with radicular pain (30).

What influences the pain?

Does the size of the herniation matter in whether you experience pain? And is there a linear relationship between size and pain? And what about the person experiencing the pain? Let’s look into this.

First, we need to take a brief look at what is what.

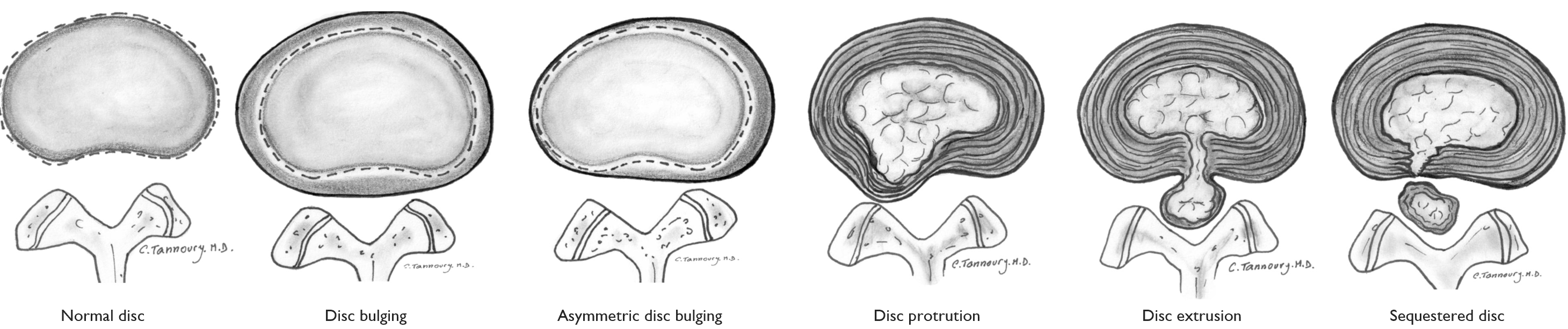

Protrusion, Extrusion, and Sequestration

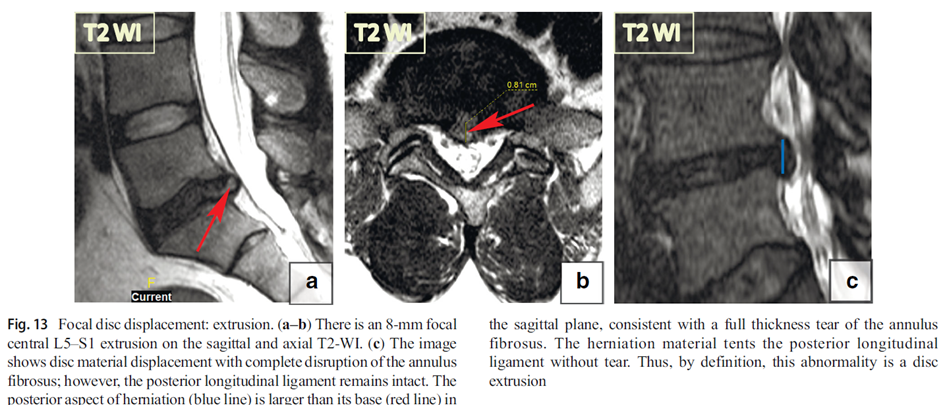

A disc herniation can be either a protrusion (the base of the herniation is thicker/wider than the herniation head) or an extrusion (the herniation head is thicker/wider than the herniation base) (1). A sequestered herniation refers to disc material that has broken off from the disc (1).

In a large study comparing surgical and conservative treatment for herniation, 27% had protrusion, 66% had extrusion, and 7% had sequestration (2). Remember, these are patients seeking treatment for back and leg pain, with pain lasting at least 6 weeks. When looking at people without pain, the numbers are different:

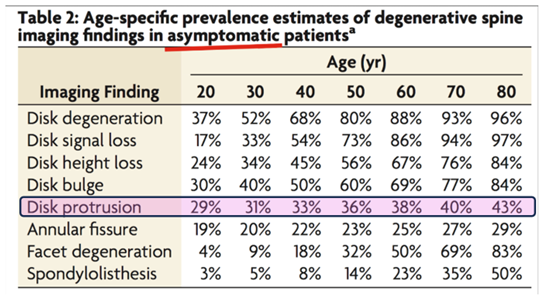

Can You See Herniations in People Without Pain?

Firstly, it should be mentioned that it is common to have herniations without pain. We can start by looking at protrusion. In the famous Brinjikji study, more than 1/3 of all people WITHOUT back pain had a protrusion (3).

Similar numbers are found in older studies, where protrusion was seen in 27% of people without pain (4).

As early as 1995, it was noted (5):

Individuals with minor disc herniations (i.e., protrusion, contained discs) are at a very high risk that their magnetic resonance images are not a causal explanation of pain because a high rate of asymptomatic subjects (63%) had comparable morphologic findings.

So, if you get an MRI and find a protrusion, it could very well not be the cause of your symptoms. It could be a coincidental finding. Therefore, it is very important to do a thorough subjective and clinical examination to see if there is a link between MRI findings and symptoms. Even though we know that 90-95% of low back pain is nonspecific (one cannot pinpoint a single cause for the symptoms), we have good tests to detect disc herniations with radiculopathy/radicular pain (6,7).

Increased Likelihood of Low Back Pain with Protrusion?

Even though many with protrusion do not experience pain, some studies show an increased likelihood of low back pain with a protrusion. In the “other” Brinjikji study, it was found that there are over twice as many people in the symptomatic group with disc protrusion (19% vs. 42%) (8). Another study also shows an increased likelihood of low back pain (significant association) in those with protrusion who are under 50 years old (8).

Protrusion and Radicular Pain?

When it comes to the link between protrusion and radicular pain, the findings are limited. Unfortunately, no large study (like Brinjikji) has been conducted to examine MRI findings and radicular pain, but there are some small studies. One study followed 46 people without low back pain, where MRI results showed protrusion. These were followed over 5 years, and 41% developed back pain, but none experienced leg pain (9). This makes sense when considering the immune response and neuroinflammation. If the disc merely “bulges” a bit, there is no disc material causing inflammation and nerve root irritation. Therefore, there is no radicular pain.

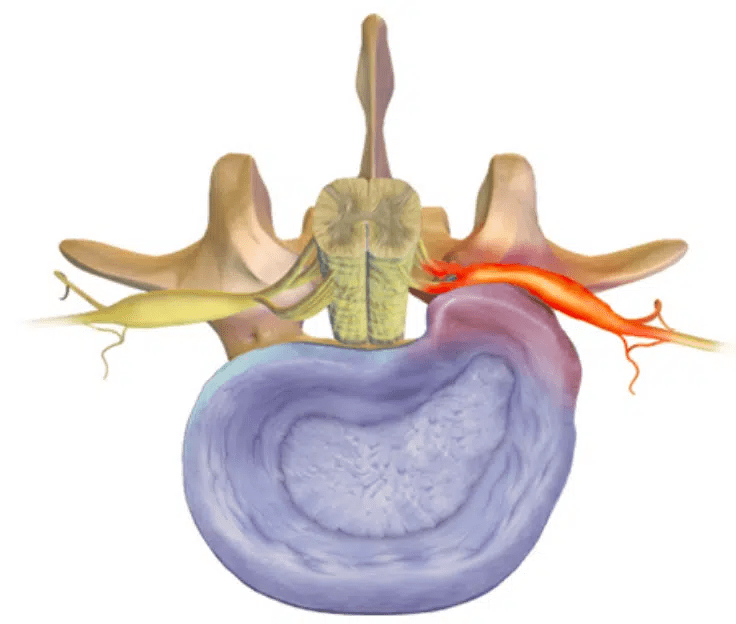

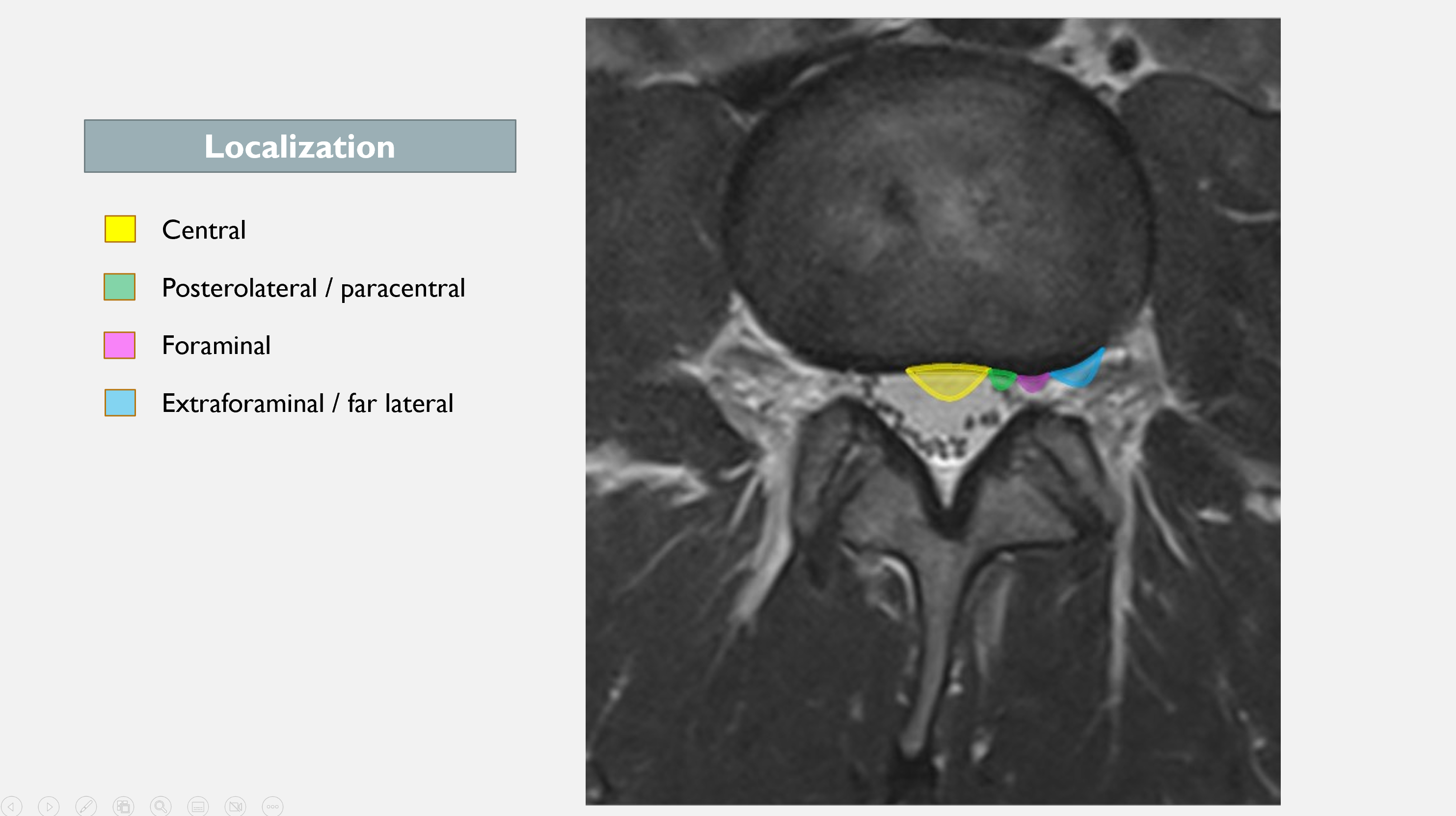

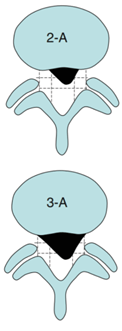

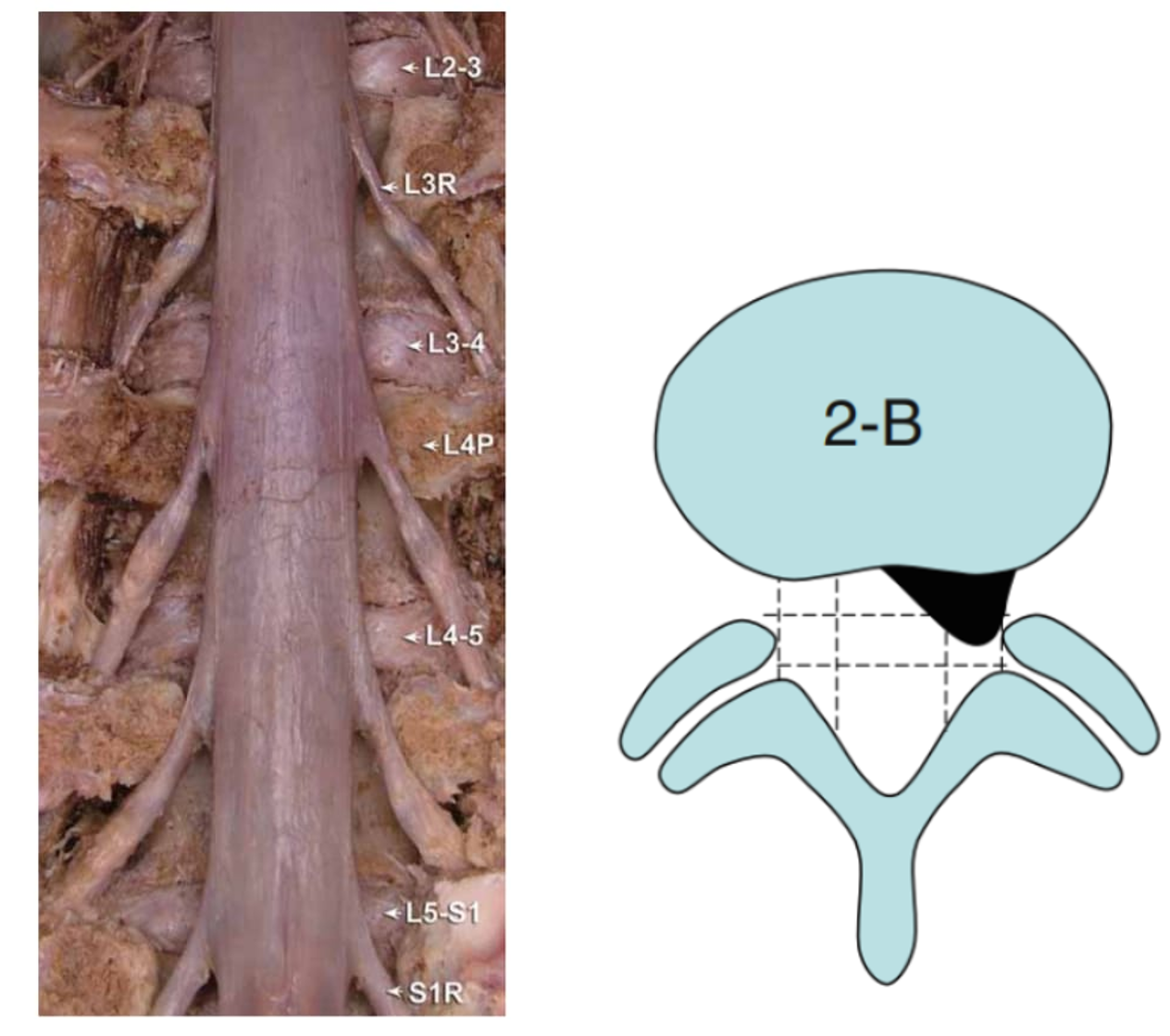

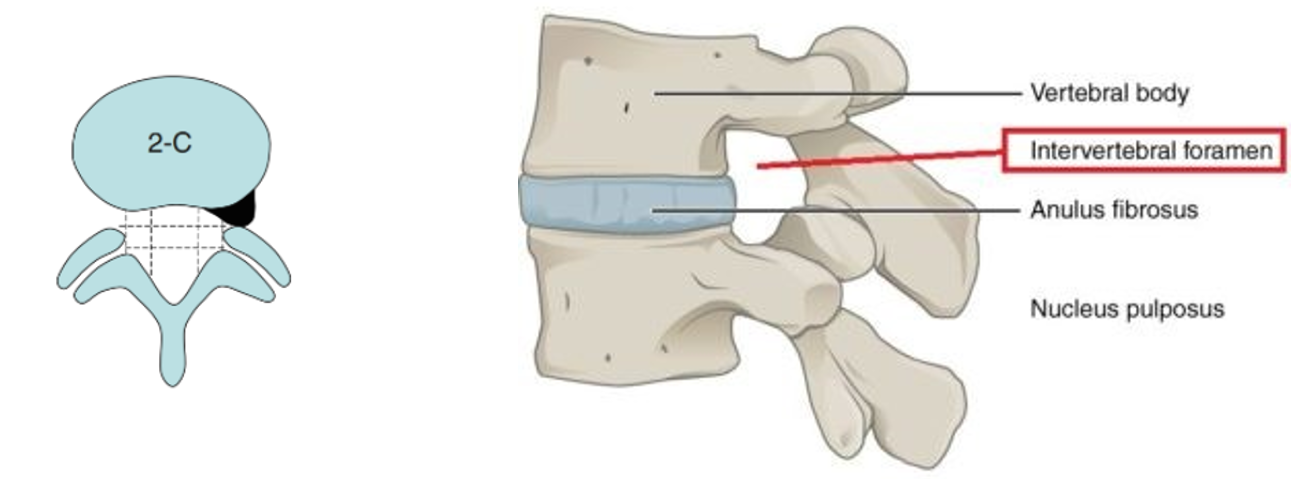

Sometimes, however, a protrusion can still cause radicular pain. Perhaps it has more to do with the location? A small central protrusion in the lower back will not cause much trouble (see image below, 1-A). There is plenty of space for nerve structures to move. A larger protrusion/extrusion in the intervertebral foramen can potentially cause more problems, as the nerve root can get pinched between the herniation and the foramen wall (see image below, 2-C) (10). More on this later.

Summary of Protrusion

Protrusion is a common finding on MRI, both in those who have pain and those who do not (3,8). There is some increased chance of experiencing back pain if you have a protrusion. BUT correlation does not imply causation. You also cannot see pain on MRI, and MRI findings cannot predict the outcome of a disc herniation (11-13). In my view, it is rare for a protrusion to cause radicular pain and radiculopathy, unless you are unlucky and have a larger protrusion in the intervertebral foramen. Note that a protrusion can likely cause somatic referred pain down the leg. It is important to foster hope and use physical activity as a tool. A protrusion is treated more like nonspecific low back pain.

Extrusion

Now we move to the next herniation type; the extrusion. This is rarely asymptomatic. In other words, extrusion often causes low back pain and is often the cause of radicular pain. In the “other” Brinjikji study, 7.1% had an extrusion in the symptomatic group, compared to 1.8% in the asymptomatic group (8). In a study that followed people without pain, five developed an extrusion. All five experienced radicular pain (12).

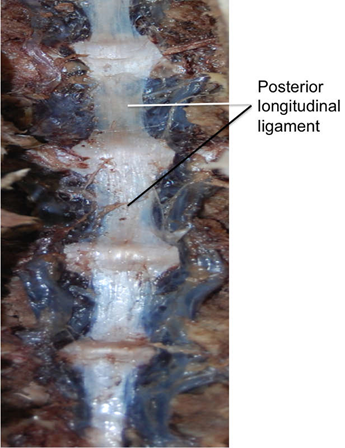

With an extrusion, disc material exits the annulus fibrosus. According to an article, the posterior longitudinal ligament often remains intact (1,14).

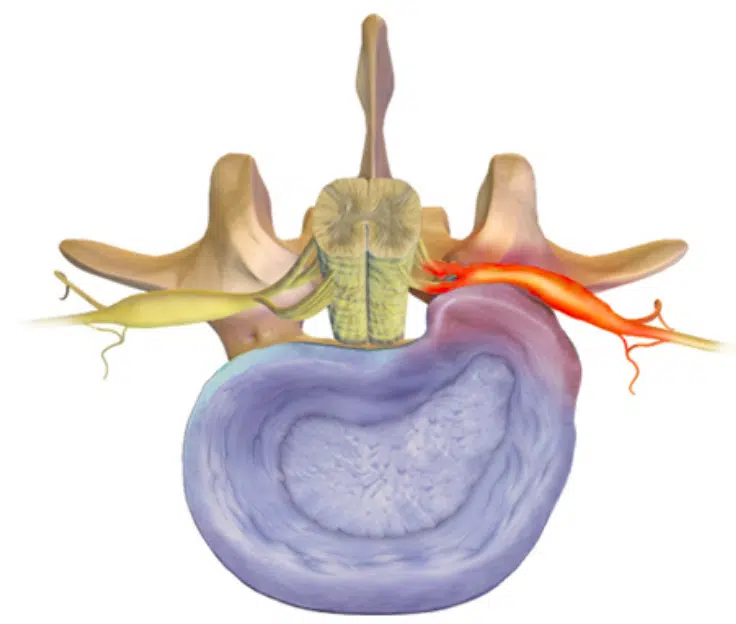

There can be several reasons why an extrusion is more painful both in the back and the leg. The pathomechanism can be mechanical, ischemic, and/or inflammatory (15).

Firstly, it is known that the outer 1/3 of the intervertebral disc is innervated (14). When a tear occurs in the disc, this can be a source of nociceptive input (14).

In the case of a herniation, disc material can also end up where it normally does not belong – in the spinal canal or behind the ligament (posterior longitudinal ligament). The body then reacts with an immune response to remove the disc material, which can create neuroinflammation (a term that has gained increasing attention in recent years). Experimental studies have shown that placing material from the nucleus pulposus near the nerve root can, in itself, be enough to cause neuroinflammation and thus radicular pain (16). The “chemical soup” from the disc material, inflammation response, and swelling can irritate the nerve, causing pain (typically in the leg). Often, this is what causes most of the symptoms initially with a herniation, and it usually lasts a few weeks/months. Nerve pain can be very painful. Toothache is often nerve pain, and it is very painful. Fortunately, pain level is poorly correlated with injury.

I often use the analogy that herniation and nerve pain are a bit like a bee sting. A bee sting also triggers a chemical irritation. There is no tissue damage, but it is very painful! Pain does not correlate well with the degree of injury. Tom Jesson (who again got it from Rob Goldsmith) uses the analogy of having chili powder on your fingers and touching your eye. It is probably the chili powder causing the discomfort, more than the pressure. Hard pressure is, of course, undesirable, but the intense pain is likely caused by chemical irritation (17). These analogies can reduce the threat level for patients.

The herniation can also press/stretch the nerve root. Often, this is a low-grade deformation of the nerve root. Initially, this may not cause many symptoms, but low-grade compression over time can create neuroinflammation of the nerve root, making it more painful and sensitive to pressure/stretch (15). Occasionally, there can be a larger compression of the nerve root. Full compression of the nerve root may actually be less painful. As a clinician, you should be vigilant when a patient has had significant radicular pain for several weeks and then suddenly no longer experiences pain. Sometimes, this may be due to complete cessation of nerve conduction. In such cases, one should check for cauda equina syndrome and radiculopathy.

Sequestration

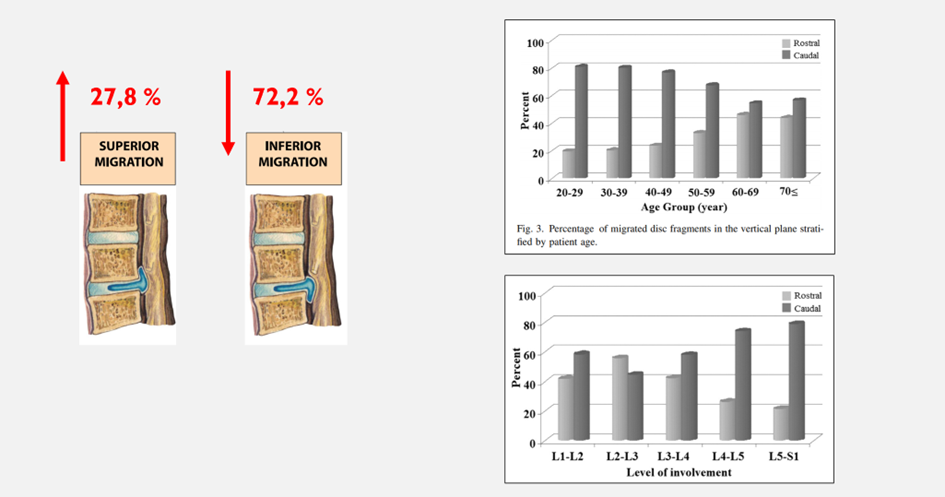

A sequestered disc herniation occurs when disc material (an extrusion) has separated from the disc (1). This is transligamentous, meaning the herniation material has broken through the ligament and entered the spinal canal (1,18). This type of herniation is very rarely (if ever) asymptomatic. With such types of herniations, there is a greater risk of compression of nerve roots/cauda equina. Surgery is more frequently performed on these types of herniations because they can compress nerve tissue. Paradoxically, these herniations also have a good prognosis with conservative treatment (19). In a study comparing surgery and conservative treatment, spontaneous regression of the herniation was observed after 6 months in the conservative treatment group. Initially, there was less pain and functional loss in those who had surgery, but after 6 months, there was no difference. Larger herniations paradoxically have a better prognosis (19). This has led to the saying “the bigger the bulge, the better,” which we will return to later.

Contained or uncontained?

Much of the difference in symptoms can be explained by whether there’s a hole in the disc wall or not, considering the immune response and neuroinflammation. One way to categorize disc herniation is contained or uncontained, i.e., whether it has broken through the annulus fibrosus/posterior longitudinal ligament or not (1). Why is this relevant? Because it can indicate the degree of symptoms and prognosis.

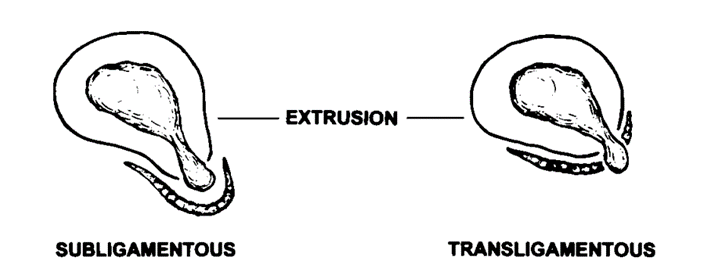

Some also use the terms subligamentous (contained) and transligamentous (uncontained) disc herniation. By definition, it is an uncontained herniation when it has broken through the wall formed by the annulus fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament. If the herniation has not completely broken through but is held back by the ligament, it is still considered a contained herniation. Why is it important to know this? Because as soon as it breaks through the wall, it creates a greater immune response, which will also affect healing and prognosis (the bigger the bulge, the better!?).

This was observed in a study of 43 patients with confirmed disc herniation on MRI. Among the patients where the herniation had broken through the ligament (transligamentous), 88% had significant resorption compared to 42% where it had not broken through the ligament (subligamentous) (18).

Tip: Talk more positive about the prognosis when there are signs that disc material has broken through the annulus fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament (extrusion/sequestration). These will have a better outcome with surgery and conservative treatment.

The bigger the bulge the better?

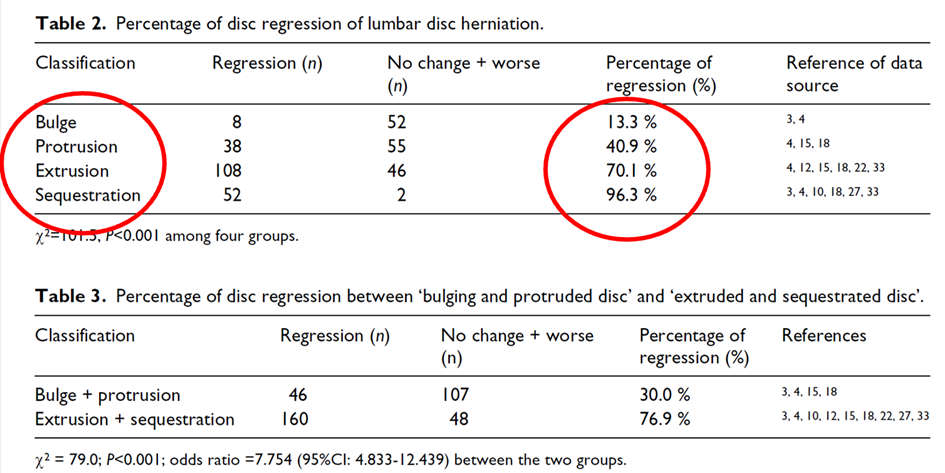

A popular saying is “the bigger the bulge, the better.” This means that larger herniations resorb (disc material is removed by the body) more than smaller herniations (20). A larger herniation provides a bigger area for the immune system to “work on.” If the disc has broken through the annulus fibrosus and ligaments, there is an even greater chance of resorption! In the spinal canal, there are more blood vessels, and thus macrophages. This creates a larger immune-inflammatory response. The body thinks “there is something here that shouldn’t be here,” and it will try to clear it out (17,21). With sequestration (as we remember, the material comes freely into the spinal canal), there is a 96.3% regression of disc material, compared to 13.3% with a disc bulge (20).

Here, we see that the most resorption occurs with sequestration and extrusion (20).

More Pain with Larger Herniations?

After reading about the three types of herniations, you might think that sequestration is the most painful? If we only look at pain, the size of the herniation is not correlated with the level of pain (17,22). However, it is observed that herniation size correlates with neurological deficits (loss of strength, reflexes, and sensation) (23). It also seems that it goes better for those where the herniation shrinks in size in the short to medium term, but the “importance” of a herniation diminishes over time (17). It is a paradox that patients with radicular pain WITH muscle weakness more often have a greater chance of improvement than those who ONLY have radicular pain.

What is in a Herniation, and Does it Matter?

The composition of the herniation also matters for healing. Bone and cartilage are more resistant to resorption compared to tissue from the nucleus pulposus. Previously, it was thought that it was mostly nucleus pulposus that went into the spinal canal, but it is now seen that there is also cartilage, endplate, and bone. If the herniation is large, it can be covered with granulation tissue. It can be imagined that a larger piece of cartilage in the spinal canal can cause more problems and a poorer prognosis (1,17,24).

Does the Location of the Herniation Matter?

The location of the herniation can be crucial for symptoms and whether there is radicular pain. It is common to categorize as follows:

1. Central

A central herniation is better and less likely to cause radiculopathy (unless it is a large herniation = cauda equina). The nerve has a better chance of escaping! It is unlikely that a small central herniation (protrusion) will cause significant symptoms, and it is less likely that an extrusion will cause long-term radicular pain – beyond the initial chemical irritation.

2. Posterolateral/Paracentral Herniation

If you have a patient with a herniation and radiculopathy, it is most likely a paracentral location. Over 3/4 of disc herniations occur paracentrally (2). In this area, the annulus fibrosus is thinner and lacks support from the posterior longitudinal ligament. It is a short distance to the nerve root (25). Nearly all lumbar herniations occur at L4/5 and L5/S1, making it likely that the L5 or S1 nerve root is affected.

3. Foraminal/Far Lateral Herniation

You can have patients with leg pain, negative SLR/Lasegue, who still have a herniation with severe radicular pain. These can have a foraminal herniation.

Foraminal and extraforaminal disc herniations are less common (7-12% / 21%) than central and paracentral ones (26). These herniations can affect the nerve root at the same level where it exits the intervertebral foramen. These patients can have stronger levels of symptoms, as disc material can enter a narrower canal with limited space for nerve displacement. The dorsal root ganglion is also located here, which is also a potentially pain-sensitive structure (27,28). A study confirms this, as these patients had more radiating leg pain compared to central and paracentral disc herniations (26).

Does Nerve Root Involvement Matter?

On many MRI images, it says nerve root involvement, or possible/mild involvement of the nerve root. Or perhaps it says “touching the nerve root.” Can these also be asymptomatic, or will they always cause problems?

According to one source, compression of the nerve root is seen in only 2-5% of asymptomatic individuals (15). Another study by Boos et al. (1995) showed that 22% of asymptomatic individuals had a mostly minor nerve root involvement, while 83% of symptomatic individuals had a mostly larger nerve root involvement (5). On the other hand, about 1/3 of those with nerve root compression seen on MRI do not have clinical signs of radiculopathy; the relationship between nerve root compression and the degree of radicular pain is disproportionate (15,17,29).

I believe that nerve roots can tolerate some traction and stretch. So, the MRI findings where it says that the herniation touches/possibly/mildly affects the nerve root are probably of minor significance. Larger nerve root involvement is significant and is more likely to cause problems.

Summary

There is a slightly increased chance of lower back pain with a protrusion, but many individuals with protrusions do not experience lower back pain. The likelihood of radicular pain and radiculopathy with a protrusion is low unless the herniation is positioned in a particularly narrow space. Remember, pain cannot be seen on an MRI – a thorough history and examination will provide more insights. An extrusion and sequestration are often painful (though there are exceptions) and frequently cause radicular pain and radiculopathy (at least in the beginning). The size of the herniation is not correlated with pain, and in the short to medium term, it is more the chemical reaction from the herniation that causes pain. Nerve root involvement is often troublesome, although there are some conflicting findings in the literature. The larger the herniation, the greater the chance of resorption, and it is observed that outcomes are somewhat better in cases where the herniation resorbs more.

References

1. Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, Murtagh FR, Gabriel Rothman SL, Sze GK. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2.0: Recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine J. 2014 Nov 1;14(11):2525–45.

2. Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Tosteson ANA, Zhao W, Morgan TS, Abdu WA, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: eight-year results for the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine. 2014 Jan 1;39(1):3–16.

3. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, et al. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015 Apr;36(4):811–6.

4. Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 14;331(2):69–73.

5. Boos N, Rieder R, Schade V, Spratt KF, Semmer N, Aebi M. 1995 Volvo Award in clinical sciences. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging, work perception, and psychosocial factors in identifying symptomatic disc herniations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Dec 15;20(24):2613–25.

6. van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, del Real MTG, Hutchinson A, et al. Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006 Mar;15 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S169-191.

7. Tawa N, Rhoda A, Diener I. Accuracy of clinical neurological examination in diagnosing lumbo-sacral radiculopathy: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 Dec;18(1):93.

8. Brinjikji W, Diehn FE, Jarvik JG, Carr CM, Kallmes DF, Murad MH, et al. MRI Findings of Disc Degeneration are More Prevalent in Adults with Low Back Pain than in Asymptomatic Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015 Dec;36(12):2394–9.

9. Elfering A, Semmer N, Birkhofer D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Risk factors for lumbar disc degeneration: a 5-year prospective MRI study in asymptomatic individuals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Jan 15;27(2):125–34.

10. Janardhana AP, Rajagopal, Rao S, Kamath A. Correlation between clinical features and magnetic resonance imaging findings in lumbar disc prolapse. Indian J Orthop. 2010;44(3):263–9.

11. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018 09;391(10137):2356–67.

12. Suri P, Boyko EJ, Goldberg J, Forsberg CW, Jarvik JG. Longitudinal associations between incident lumbar spine MRI findings and chronic low back pain or radicular symptoms: retrospective analysis of data from the longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBACK). BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014 May 13;15(1):152.

13. Han CS, Maher CG, Steffens D, Diwan A, Magnussen J, Hancock EC, et al. Some magnetic resonance imaging findings may predict future low back pain and disability: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2023 Apr;69(2):79–92.

14. Kushchayev SV, Glushko T, Jarraya M, Schuleri KH, Preul MC, Brooks ML, et al. ABCs of the degenerative spine. Insights Imaging. 2018 Apr;9(2):253–74.

15. Schmid AB, Tampin B. Section 10, Chapter 10: Spinally Referred Back and Leg Pain – International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. In: Boden SD, editor. Lumbar Spine Online Textbook [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www.wheelessonline.com/ISSLS/section-10-chapter-10-spinally-referred-back-and-leg-pain/

16. Rothman SM, Guarino BB, Winkelstein BA. Spinal microglial proliferation is evident in a rat model of painful disc herniation both in the presence of behavioral hypersensitivity and following minocycline treatment sufficient to attenuate allodynia. J Neurosci Res. 2009 Sep;87(12):2709–17.

17. Jesson T. Understanding sciatica. 2023.

18. Seo JY, Roh YH, Kim YH, Ha KY. Three-dimensional analysis of volumetric changes in herniated discs of the lumbar spine: does spontaneous resorption of herniated discs always occur? Eur Spine J. 2016 May;25(5):1393–402.

19. Sucuoğlu H, Barut AY. Clinical and Radiological Follow-Up Results of Patients with Sequestered Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Prospective Cohort Study. Medical Principles and Practice. 2021 Feb 18;30(3):244–52.

20. Chiu CC, Chuang TY, Chang KH, Wu CH, Lin PW, Hsu WY. The probability of spontaneous regression of lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015 Feb;29(2):184–95.

21. Cunha C, Silva AJ, Pereira P, Vaz R, Gonçalves RM, Barbosa MA. The inflammatory response in the regression of lumbar disc herniation. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2018 Nov 6;20(1):251.

22. Jensen OK, Nielsen CV, Sørensen JS, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Back pain was less explained than leg pain: a cross-sectional study using magnetic resonance imaging in low back pain patients with and without radiculopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015 Dec 3;16(1):374.

23. Nv A, Rajasekaran S, Ks SVA, Kanna RM, Shetty AP. Factors that influence neurological deficit and recovery in lumbar disc prolapse-a narrative review. Int Orthop. 2019 Apr;43(4):947–55.

24. Brock M, Patt S, Mayer HM. The form and structure of the extruded disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992 Dec;17(12):1457–61.

25. Dulebohn SC, Ngnitewe Massa R, Mesfin FB. Disc Herniation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441822/

26. Lee JH, Lee SH. Clinical and Radiological Characteristics of Lumbosacral Lateral Disc Herniation in Comparison With Those of Medial Disc Herniation. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2016 Feb 18 [cited 2020 Mar 23];95(7). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4998615/

27. Epstein NE. Foraminal and far lateral lumbar disc herniations: surgical alternatives and outcome measures. Spinal Cord. 2002 Oct;40(10):491–500.

28. Park HW, Park KS, Park MS, Kim SM, Chung SY, Lee DS. The Comparisons of Surgical Outcomes and Clinical Characteristics between the Far Lateral Lumbar Disc Herniations and the Paramedian Lumbar Disc Herniations. Korean J Spine. 2013 Sep;10(3):155–9.

29. Karppinen J, Malmivaara A, Tervonen O, Pääkkö E, Kurunlahti M, Syrjälä P, et al. Severity of symptoms and signs in relation to magnetic resonance imaging findings among sciatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Apr 1;26(7):E149-154.

30. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep [Internet]. 2020 Jul 22 [cited 2020 Sep 24];5(4). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7382548/