As a clinician, you’ve probably heard patients say that they’ve had an MRI showing disc bulges and that this is what’s causing their symptoms. Some patients may even say they have a herniated disc when the MRI shows disc bulging. Is disc bulging the same as herniated disc, and does it cause pain? First, let’s take a brief look at what is what.

What is a disc bulge?

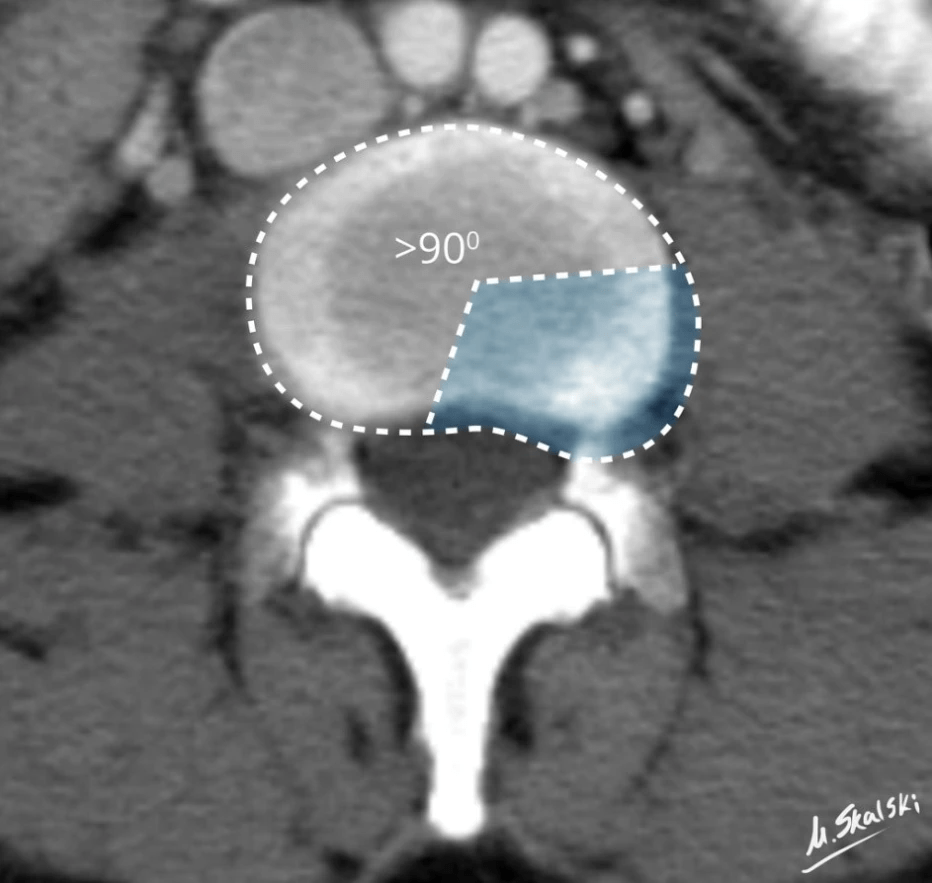

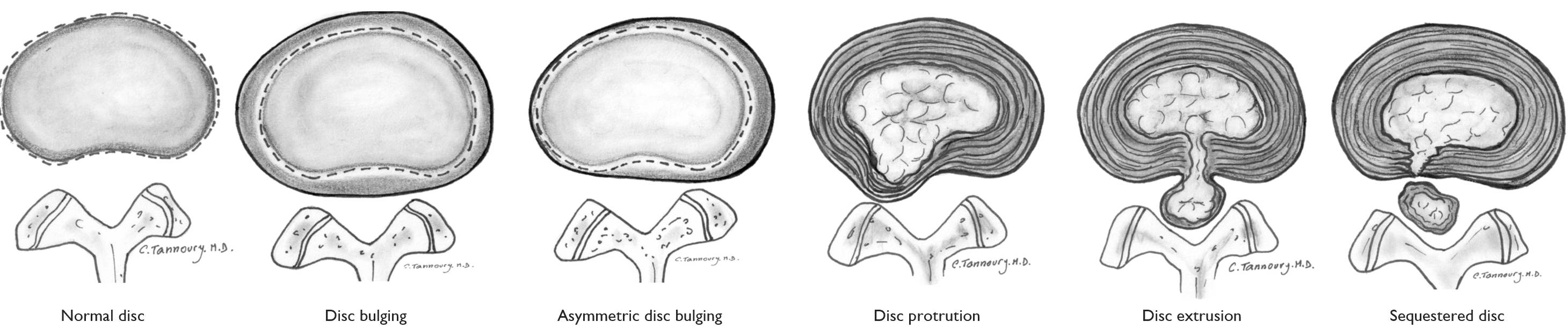

A disc herniation is a localized displacement of material. By localized, we mean a minor displacement. When looking from above onto the disc, 25% or less of the disc should be displaced beyond the bone itself to be called a herniation. If it’s more than 25%, it’s called a disc bulge (1).

Can disc bulging be found in those without pain?

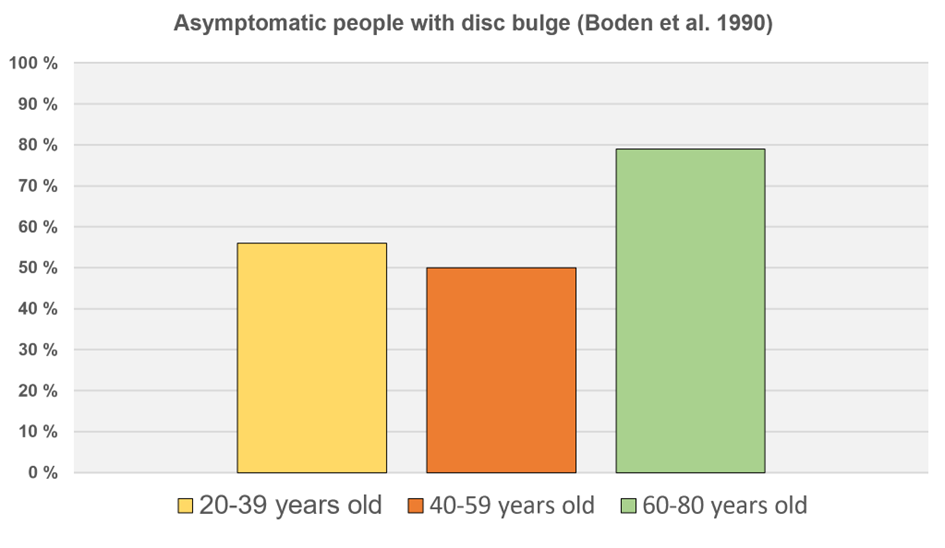

Disc bulging is a very common finding in those without pain, and this has been known for a long time. Back in 1990, Boden et al. conducted a study on asymptomatic individuals (2):

As you can see, there is a large percentage with disc bulging. I repeat, these individuals do not have pain (2). To make it even clearer:

Another major study by Jensen et al. in 1994 (3) showed a high incidence of disc bulging in 98 asymptomatic volunteers. They found that 52% had disc bulging at one or more levels, in those without pain. Comparing it with those with lower back pain, these figures from a study with 4233 patients don’t show much higher incidence (65.2%) (4).

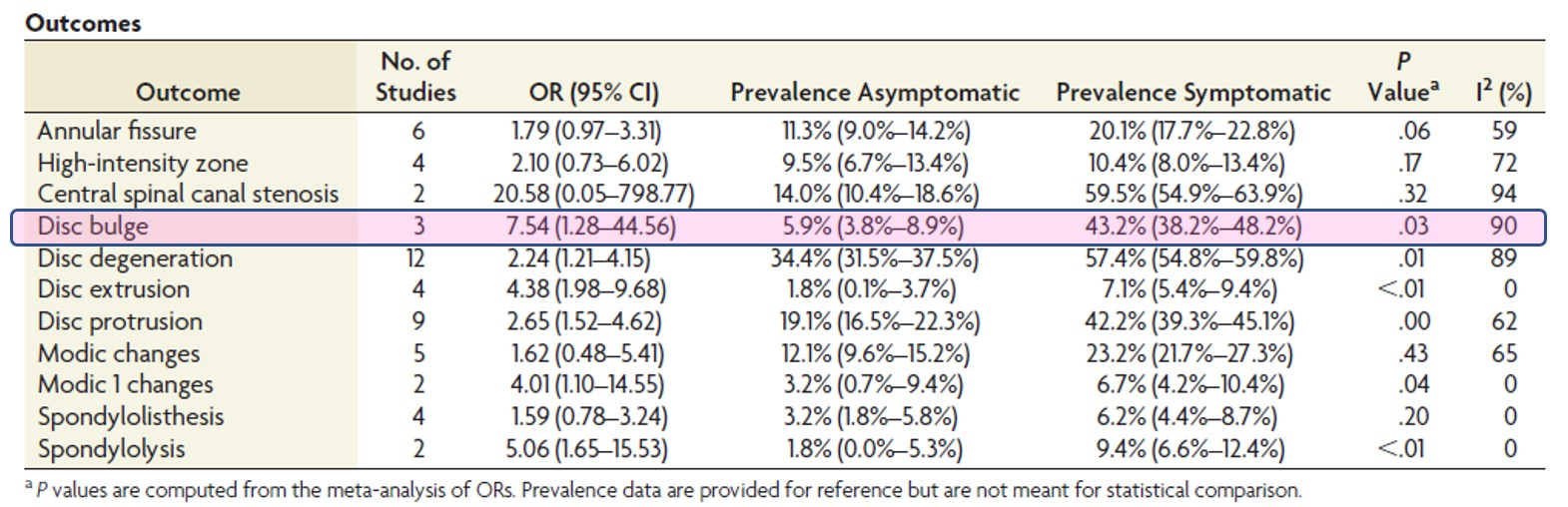

A study that many MSK clinicians are probably familiar with is this one by Brinjikji et al. (5), who conducted a systematic review of MRI findings in the lumbar spine of people without lower back pain:

Here you can see a very high incidence of disc bulging with increasing age – a normal finding!

I also think it’s not surprising that it doesn’t hurt. Nothing in the disc has ruptured. It just bulges out. The same thing happens to your stomach after you’ve eaten too much Christmas food. There’s no inflammatory process to “fix things” (there’s nothing that needs to be “fixed”), and there’s nothing compressing the nerve root.

Can disc bulging still contribute to the patient’s symptoms?

It is somewhat interesting that Brinjikji and others published another study around the same time that hardly received any attention (6). The second Brinjikji study shows a higher prevalence of disc degeneration in those with lower back pain compared to those without symptoms. Tom Jesson jokingly called it “the study who must not be named.” (Of course, I find the study with the asymptomatic individuals most interesting, but it also made me uncertain whether it “can never mean anything for the patient’s symptoms”).

In this study, they compared symptomatic versus asymptomatic individuals.

There is a significant difference in the percentage of disc bulging between those with symptoms and those without symptoms based on these figures: 5.9% in asymptomatic individuals and 43.2% in symptomatic individuals. I don’t know where they get the 5.9% figure from for asymptomatic individuals; to me, it seems very low compared to the other studies I’ve mentioned, e.g., Boden et al.

The Lancet article from 2018 (yes, this reference is getting a bit old, but it’s very good) also states that some MRI findings, including disc bulging, have a fairly strong association with lower back pain (7).

Conclusion?

To summarize, many people with disc bulging have back pain, but many people with disc bulging do not have back pain. I think disc bulging should be seen more as a normal phenomenon, not a sign of injury or disease. Disc bulging itself does not compress the nerve root and is not an explanation for persistent sciatica (8). There is insufficient evidence that MRI findings predict future lower back pain or indicate how the person with lower back pain will fare (7).

So what causes lower back pain?

If you have lower back pain, you have an MRI and find only a few disc bulges (it probably wasn’t indicated to take an MRI in the first place?), then by definition, you have non-specific low back pain (even though there are people who question the label NSLBP, and thinks we can be more precise in our diagnosis (11)). This is the largest group within lower back pain, with an 85-90% incidence (7,9). Nonspecific low back pain means that it cannot be definitively said that a specific structure is the source of the pain. I think one must look broadly at these patients. Get them started on activity if they are inactive, improve sleep, challenge beliefs and thoughts, vary sitting positions. Yes, maybe some have some changes in their back that make it slightly more likely to cause pain, but it’s not black and white.

Tinder and fire

I usually imagine this analogy, made by Greg Lehman (12), which describes structural changes in the back. The tinder are there in the form of structural changes. A spark can come, and you can experience more pain. This spark can be physical and psychological stressors, e.g., a full day of unusual strain, renovating an apartment, carrying a sofa, poor sleep health, a lot of negative stress, depression, and the like. Some have more embers than others. Often it’s also random when the symptoms can worsen.

Luis Gifford also said something like “when you’re low you hurt more easily“. Which brings us to the next analogy.

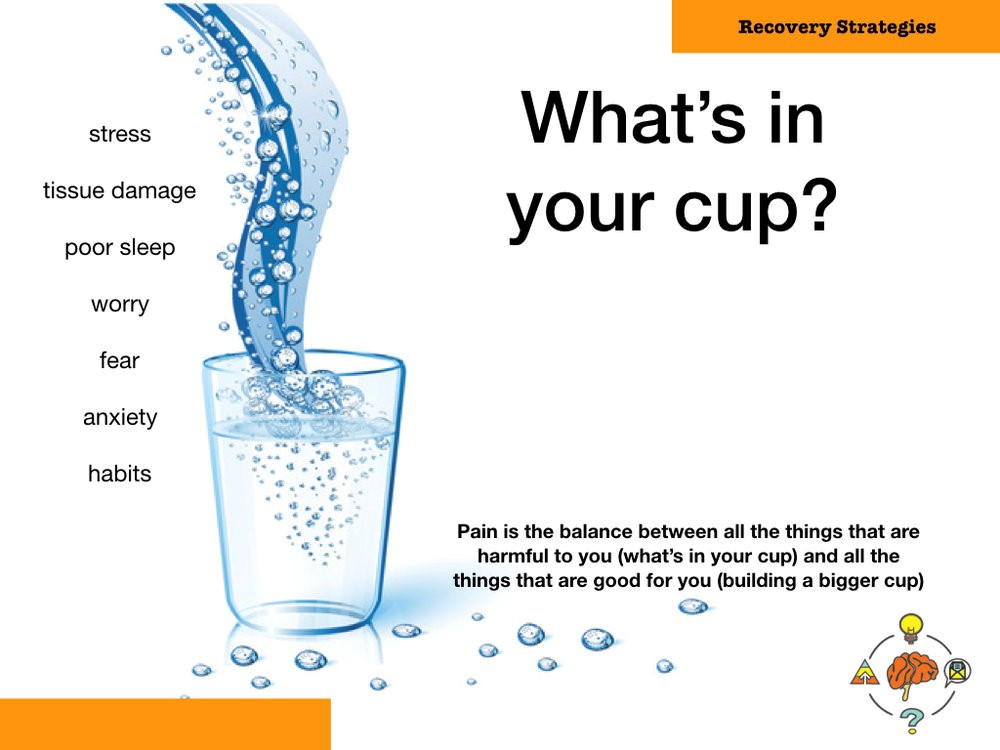

I also use Greg Lehman’s model (or someone before him?) to describe the path to improvement: The Cup and Water metaphor (10). You can either build a bigger cup (increase capacity) or remove some of the water (remove stressor). Read his article on this here.

Communication

I think it is important to reflect upon how you talk about MRI results to the patient. Will you say to the patient that they have a disc bulge? Will you not mention it? Will you say they have non-specific low back pain? Will you not say anything at all? You will probably have to adjust the answer, depending on the patient. I usually go for less threatening labels, like “sprained back“, “common back pain” (in Norwegian). These labels can potentially lead to less use of MRI, surgery and second opinion (13).

Summary

Disc bulging is not a herniated disc. It’s a common finding in those without pain but may be more present in those with lower back pain. It’s important to note that MRI findings cannot predict future lower back pain or how the person with lower back pain will fare. Disc bulging is considered nonspecific lower back pain and should be treated according to the biopsychosocial model.

References

1. Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, Murtagh FR, Gabriel Rothman SL, Sze GK. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2.0: Recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine J. 1. november 2014;14(11):2525–45.

2. Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. mars 1990;72(3):403–8.

3. Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 14. juli 1994;331(2):69–73.

4. Albert HB, Briggs AM, Kent P, Byrhagen A, Hansen C, Kjaergaard K. The prevalence of MRI-defined spinal pathoanatomies and their association with modic changes in individuals seeking care for low back pain. Eur Spine J. august 2011;20(8):1355–62.

5. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, mfl. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. april 2015;36(4):811–6.

6. Brinjikji W, Diehn FE, Jarvik JG, Carr CM, Kallmes DF, Murad MH, mfl. MRI Findings of Disc Degeneration are More Prevalent in Adults with Low Back Pain than in Asymptomatic Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. desember 2015;36(12):2394–9.

7. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, mfl. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 09 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

8. Ropper AH, Zafonte RD. Sciatica. N Engl J Med. 26. mars 2015;372(13):1240–8.

9. O’Sullivan P. It’s time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med. mars 2012;46(4):224–7.

10. Do our patient’s need fixing? Or do they need a bigger cup? [Internett]. Greg Lehman. [sitert 3. april 2022]. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.greglehman.ca/blog/2018/5/1/do-our-patients-need-fixing

11. Han CS, Hancock MJ, Sharma S, Sharma S, Harris IA, Cohen SP, et al. Low back pain of disc, sacroiliac joint, or facet joint origin: a diagnostic accuracy systematic review. eClinicalMedicine

12. Greg Lehman [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2024 Apr 18]. Tissue changes and pain: explaining their relevance. Available from: https://www.greglehman.ca/blog/2017/3/6/tissue-changes-and-pain-explaining-their-relevance

13. O’Keeffe M, Ferreira GE, Harris IA, Darlow B, Buchbinder R, Traeger AC, et al. Effect of diagnostic labelling on management intentions for non‐specific low back pain: A randomized scenario‐based experiment. Eur J Pain. 2022 Aug;26(7):1532–45.