What is a dermatome?

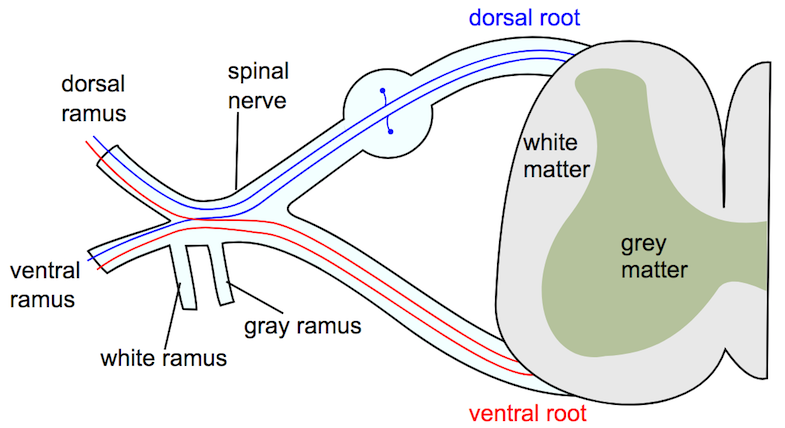

Dermatome means ‘skin section’ and refers to a correspondence between the skin and the nervous system (1,2). A dermatome is thus a skin area supplied by a nerve root (1). Afferent (conveying information from a peripheral structure to the central or center) nerve impulses from the skin, among other sources, pass through the posterior root, while efferent (conveying information from central to peripheral) signals go out to the muscles in the anterior root (3). It has also been observed that there is some afferent information that passes through the ventral horn (4).

History of dermatome maps

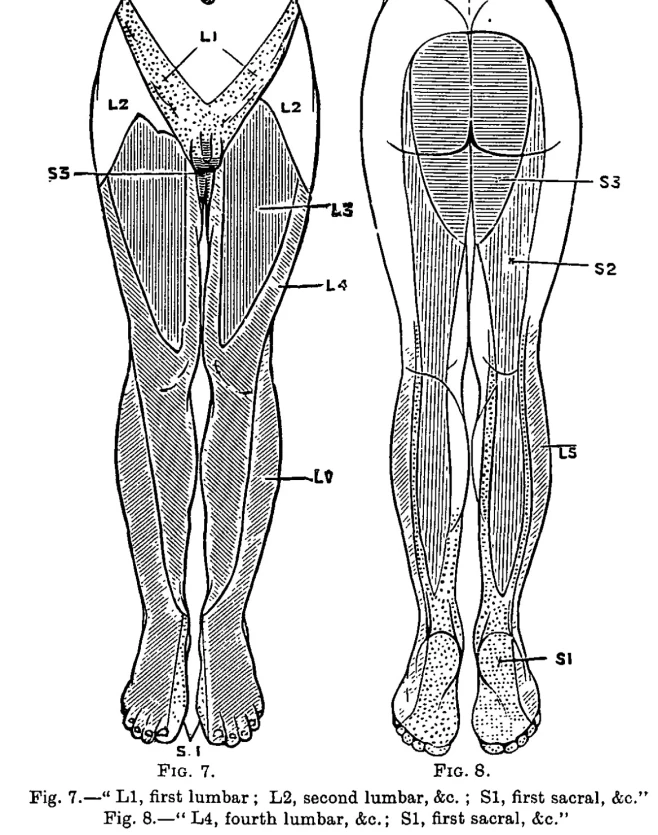

One of the first to publish dermatome maps was William Thorburn in 1893. He created a dermatome map based on patients with cauda equina syndrome and lesions in the spinal cord (5). See below.

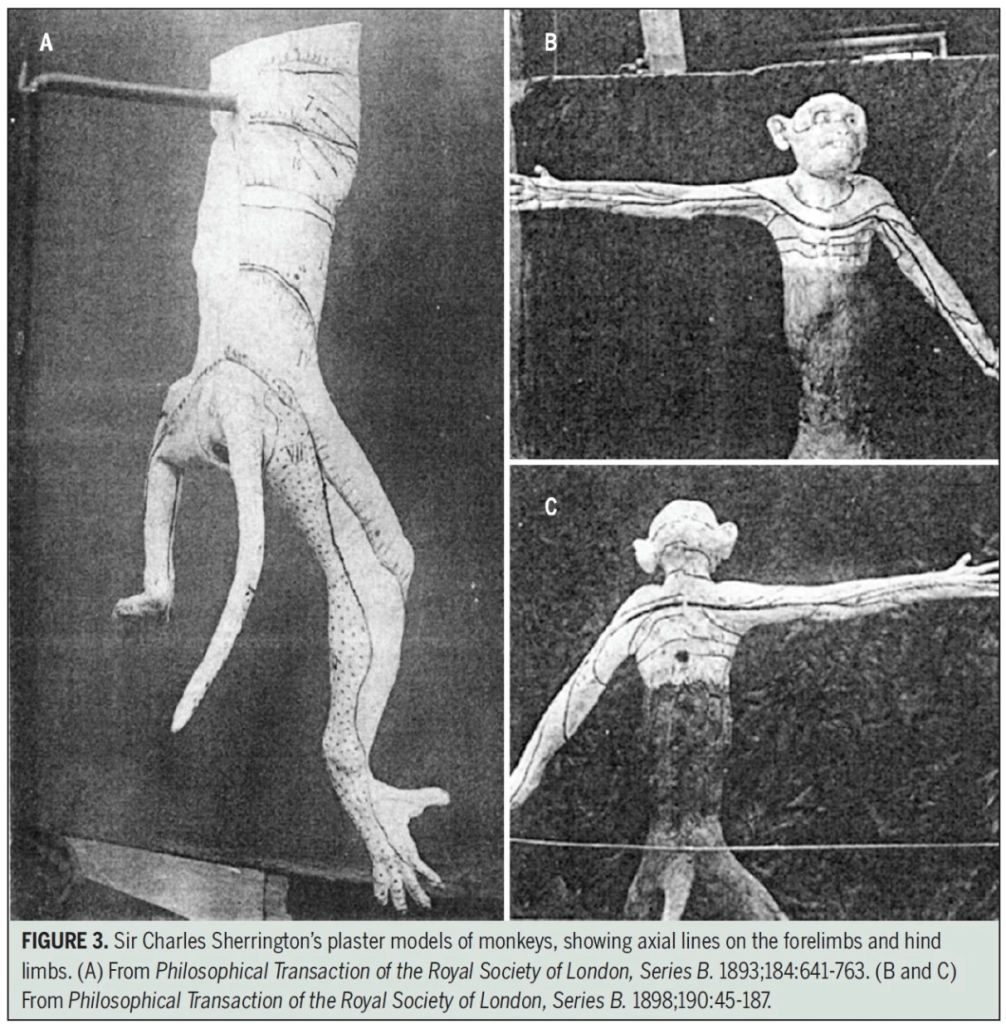

Further advancement of knowledge was made by Sherrington in the late 19th century, who researched dermatomes in apes. He cut several nerve roots above and below a certain root and examined how the nerve function of the remaining nerve root was (2).

Current Dermatome Maps

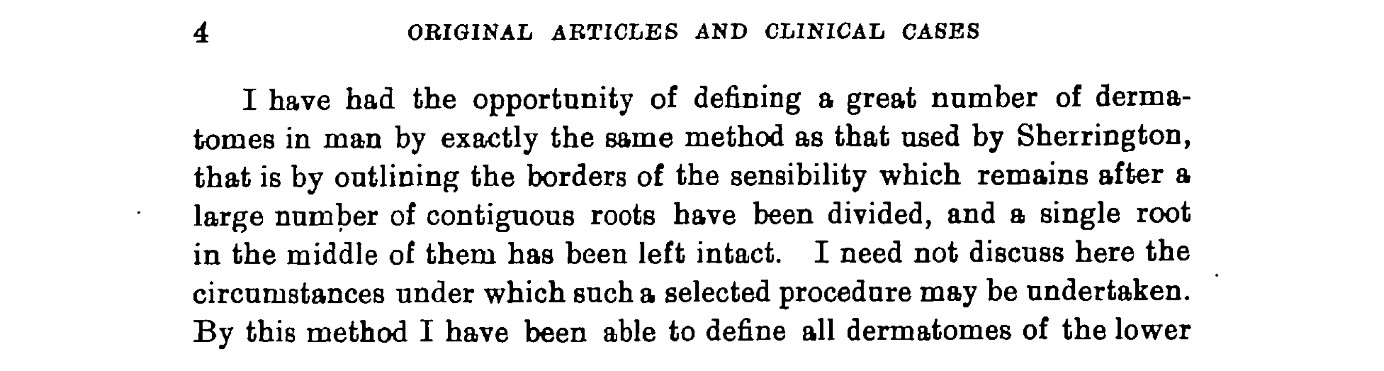

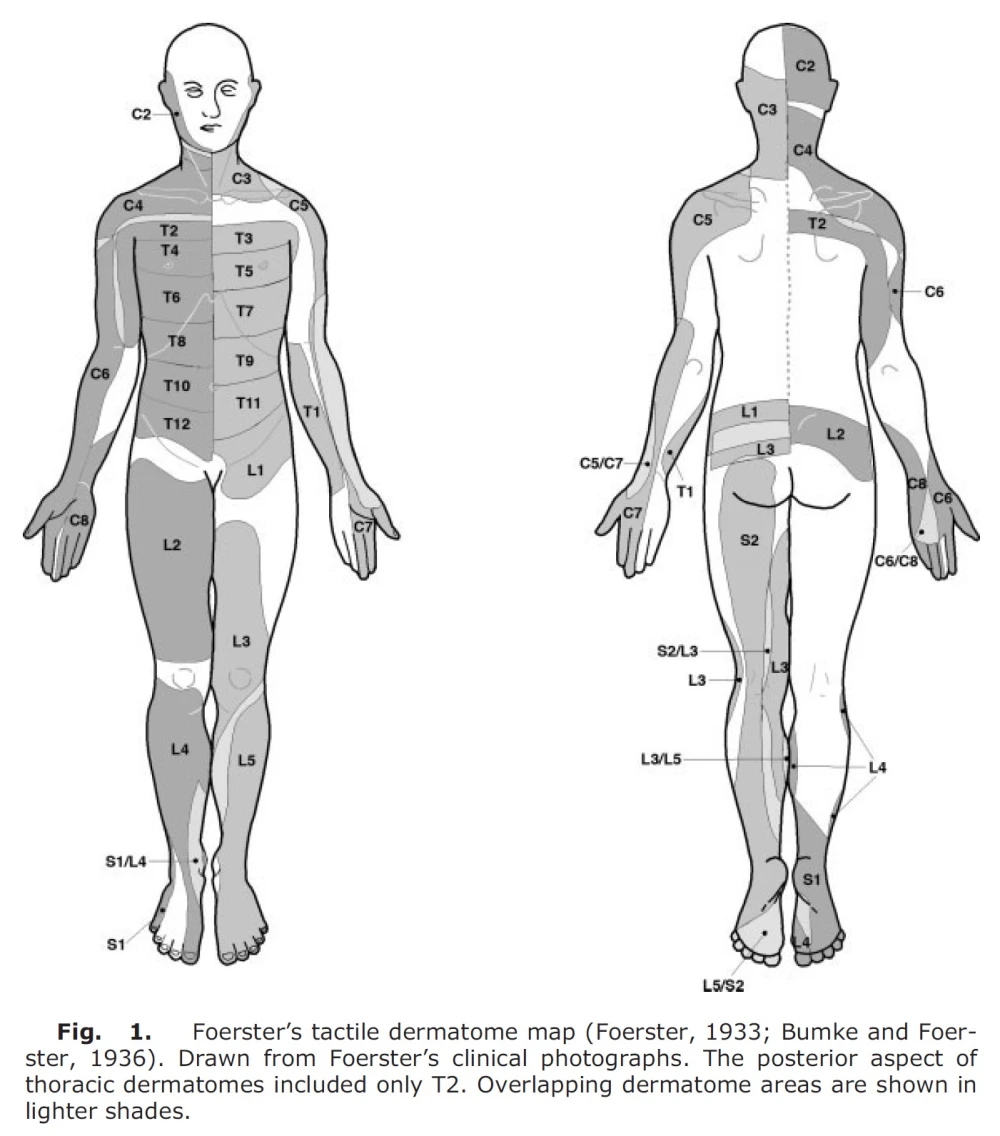

Almost all the maps used today are based on two sources, namely Foerster (6) from 1933 and Keegan and Garrett (7) from 1948 (4). The former is an example of how brutal we humans have been, even within medical science. Here, he cut the dorsal nerve roots in humans, at least two levels above and two levels below, and then tested the remaining nerve root (4). At that time, the dorsal horn of nerve roots was cut (rhizotomy) to treat patients with severe pain referred from organs and to reduce spasticity in cerebral palsy, trauma to the central nervous system, and inflammation of the spinal cord due to syphilis. In this study, it was said to treat pain, but he did not mention why a nerve root was left (8). It says in the original article from 1933:

Foerster was also German, and this was in 1933. One can imagine that this is not good. Another doctor at the time, Robert Wartenberg, said of Foerster (2):

Foerster found that dermatomes vary from person to person (excluding the midline), that tactile dermatomes overlap to a greater extent than those determined by pain and temperature, and that there is no total loss of sensation in the skin if one nerve root is cut (except for C2) (4). An unethical and cruel study, but it nevertheless formed the basis for the dermatome maps we see now.

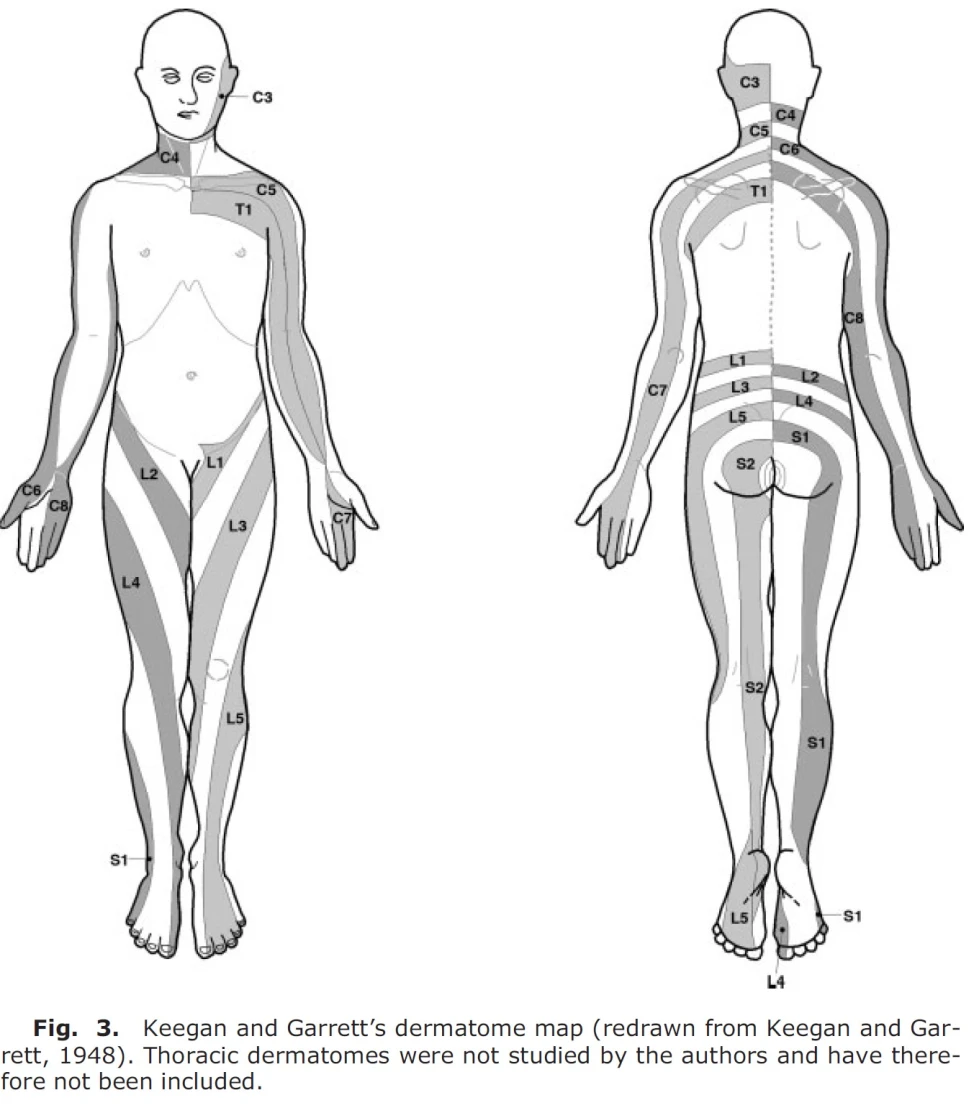

Keegan and Garrett (7) created a dermatome map in 1948 by examining patients with disc herniation with nerve root compression. They recorded sensation by light needle pricks and looked for hypoalgesia. This study has quite a few sources of error, as most of the patients were diagnosed using myelography (x-ray with contrast medium), a somewhat uncertain measurement method (4), they do not mention anything about anatomical variation, and despite other studies, there is no overlap between dermatomes (8). In this study, the dermatome was drawn in a continuous stripe all the way from the back to the leg, so for example, the L5 dermatome extended from the lower lumbar spine, gluteally, laterally to the thigh, anteriorly to the shin, and on the dorsum of the foot. This has since been disproven, among others, in a later study by Davis et al from 1952 (9), where they found that over half of the patients with lumbar disc herniation had only sensory changes in the foot and shin. Later studies have also disproved this (4). Below is the dermatome map by Keegan and Garrett from 1948, which is widely used in the literature.

Which dermatome map is best?

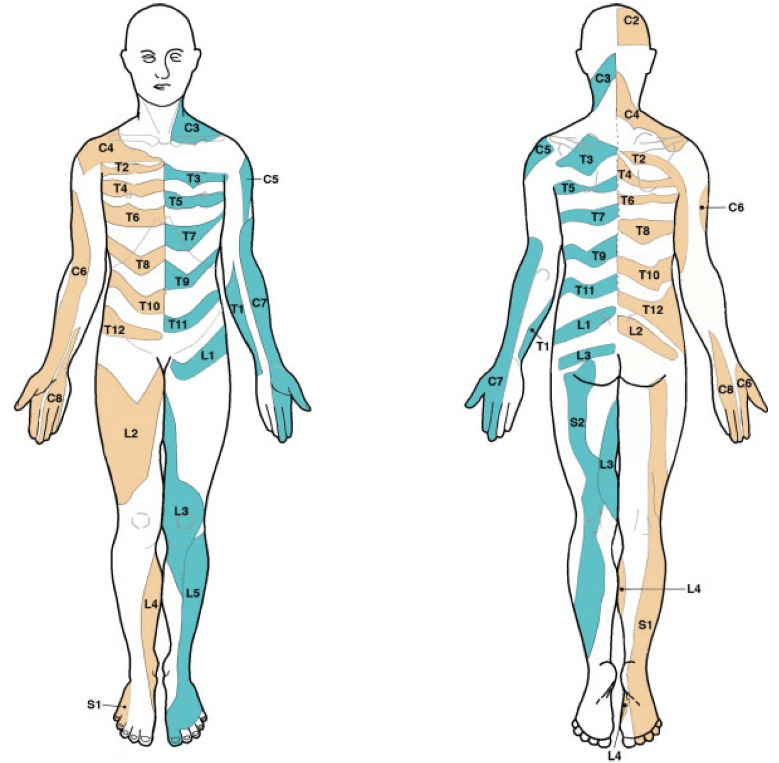

In more recent times, a study by Lee et al. from 2008 (4) has been conducted to assess the quality of previous dermatome studies and summarize them into a new and better dermatome map (image below). From my understanding, this is the best dermatome map so far. When these authors were summarizing the dermatome map, they did not use Keegan and Garrett’s map because they believed it was the most deficient (4). I myself have used Keegan and Garrett’s dermatome map switched to Lee et al.’s—not that there are extreme differences. I will probably test the L4 dermatome more medially, where I have previously tested anteriorly on the tibial edge. I will test L5 somewhat more laterally on the shin and even more posteriorly on the S1 shin.

Where to test?

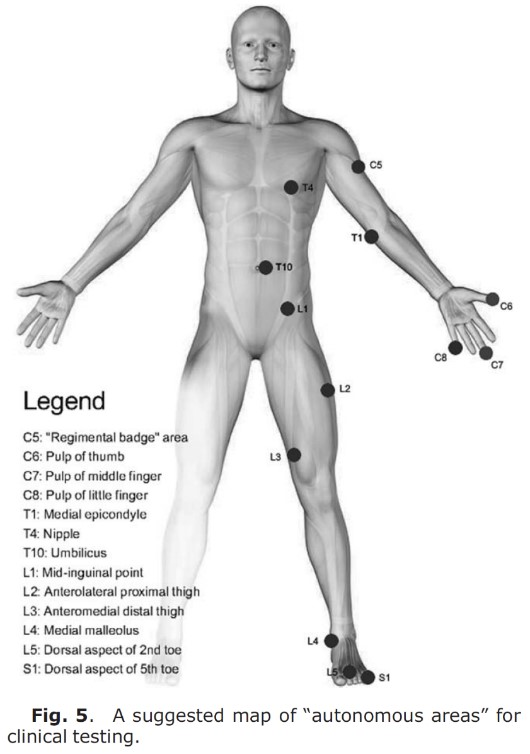

Challoumas et al. (10) built on Lee et al. (4) study and pointed out areas where one could with great certainty test a single dermatome. Dermatomes overlap to a greater extent proximally, so it is often better to test sensitivity distally (11). Certain areas are identified as “autonomous,” meaning there is no overlap (8). If you are screening dermatomes, it may be wise to test these individual areas, preferably with tests of both thick and thin nerve fibers (ref. earlier posts). Brodal (12) mentions that there is less overlap when testing pain sensation (thin) vs. touch sensation (thick), as Foerster found out. It may therefore be easier to identify sensory loss in dermatomes by testing with pinprick or a sharp object. In one study, a proposal for a map of test areas was made, see image below. If you are unsure whether it is a peripheral nerve involvement, nerve root involvement, or central involvement, you can do a more thorough examination, perhaps testing larger areas in a circular/proximal-distal pull. Nevertheless, these single points can be of great help.

Which dermatome map is used in textbooks?

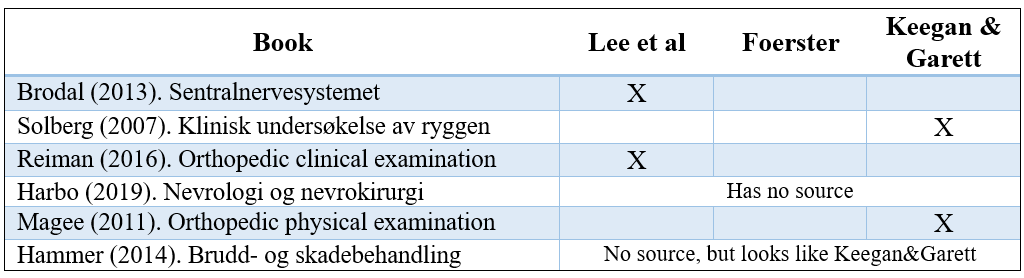

In textbooks, there is a wide variation in which dermatome map is used, and often there are no sources cited on the maps. In a study from the USA in 2011, they looked at textbooks for physiotherapy students and found that they cited the original source in only three out of fourteen books. Six had no references, and five used secondary sources.

I have done an informal check of some books I have on my shelf. Here are the results:

As you can see, many still use Keegan & Garrett. An example of how clinical reasoning can be impaired is in an L4 nerve root involvement. Books that use Foerst’s map (among others, Lee et al.) show no L4 dermatome on the thigh. If you look in other books, you can get the result that there is involvement of L2, L3, L4, or L5—depending on which source you use (8). This can be confusing!

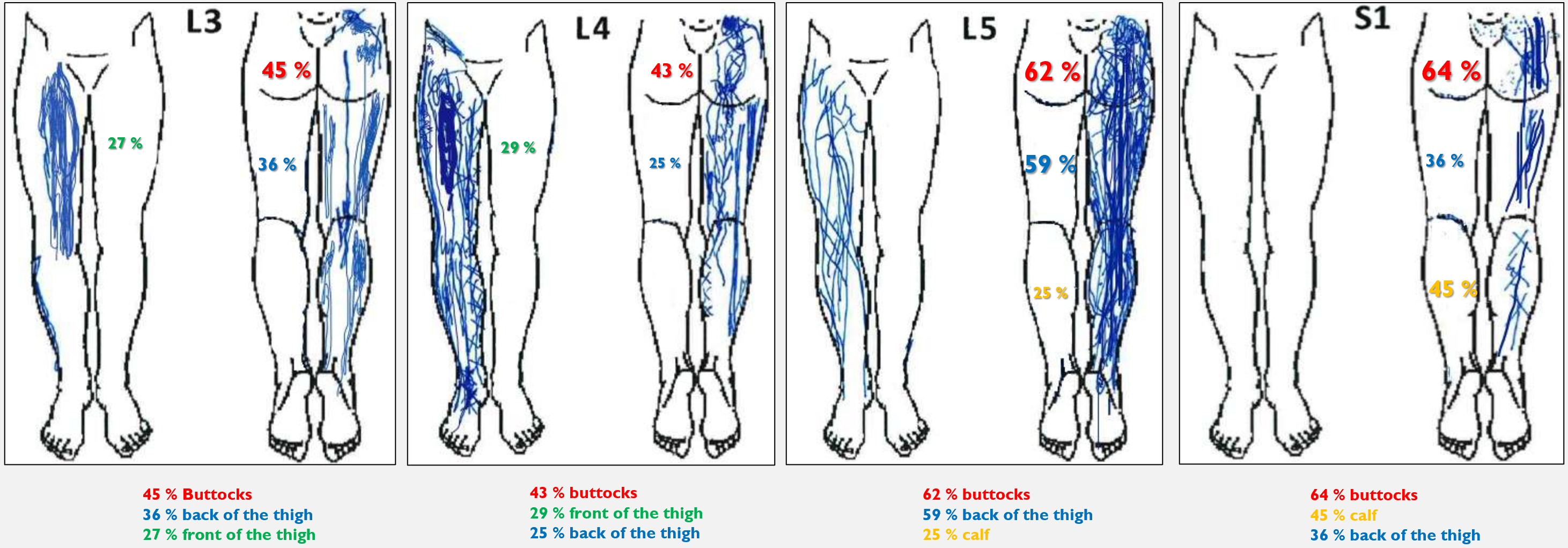

Dermatome maps are not for radicular pain

An unreflected clinician can make the classic mistake of thinking they can diagnose which nerve root/level is compromised by looking at the dermatome map and where the patient has leg pain. Previous studies suggest that one can distinguish between an L5 and an S1 involvement. They then say that an L5 involvement will typically cause pain in the anterolateral shin and dorsum of the foot, while an S1 involvement will cause pain in the posterior shin and sole of the foot (13). However, there are also several studies showing that it is not possible to distinguish between these. Pain outside the dermatome has been observed in up to 64-70% of those with radicular pain (14). Nevertheless, one exception is mentioned in the literature: with an S1 involvement, the patient often has pain in the S1 dermatome, i.e., in the back of the leg and sole of the foot.

So, to summarize—perhaps one can say that there is a greater likelihood of an S1 involvement if the patient has pain in the back of the leg and sole of the foot. But dermatome maps are primarily used to test sensitivity!

Also, see Annina Schmid’s video on how symptoms can spread with nerve tissue involvement.

Why is there such variability in dermatomes?

We have talked about variability in dermatome maps, for example, between Keegan and Lee’s maps. Another thing that can confuse is that there can also be differences between individuals.

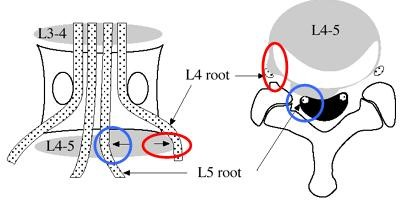

One thing is that disc herniation has the potential to compromise several nerve roots at the same level. So if you think that an L5 disc herniation will always compromise the S1 nerve root, you are mistaken. Of course, we know that about ¾ of disc herniations are posterolateral, so there is a greater likelihood of S1 root involvement, but it does not always do so (16).

A larger disc herniation can also compromise two or more nerve roots, which can confuse the clinician. It may also matter whether it is the spinal ganglion, parts of the spinal ganglion, or only the nerve root that is compromised. If the dermatome map is made from patients with disc herniation and radiculopathy, this may imply that there are several sources of error (17).

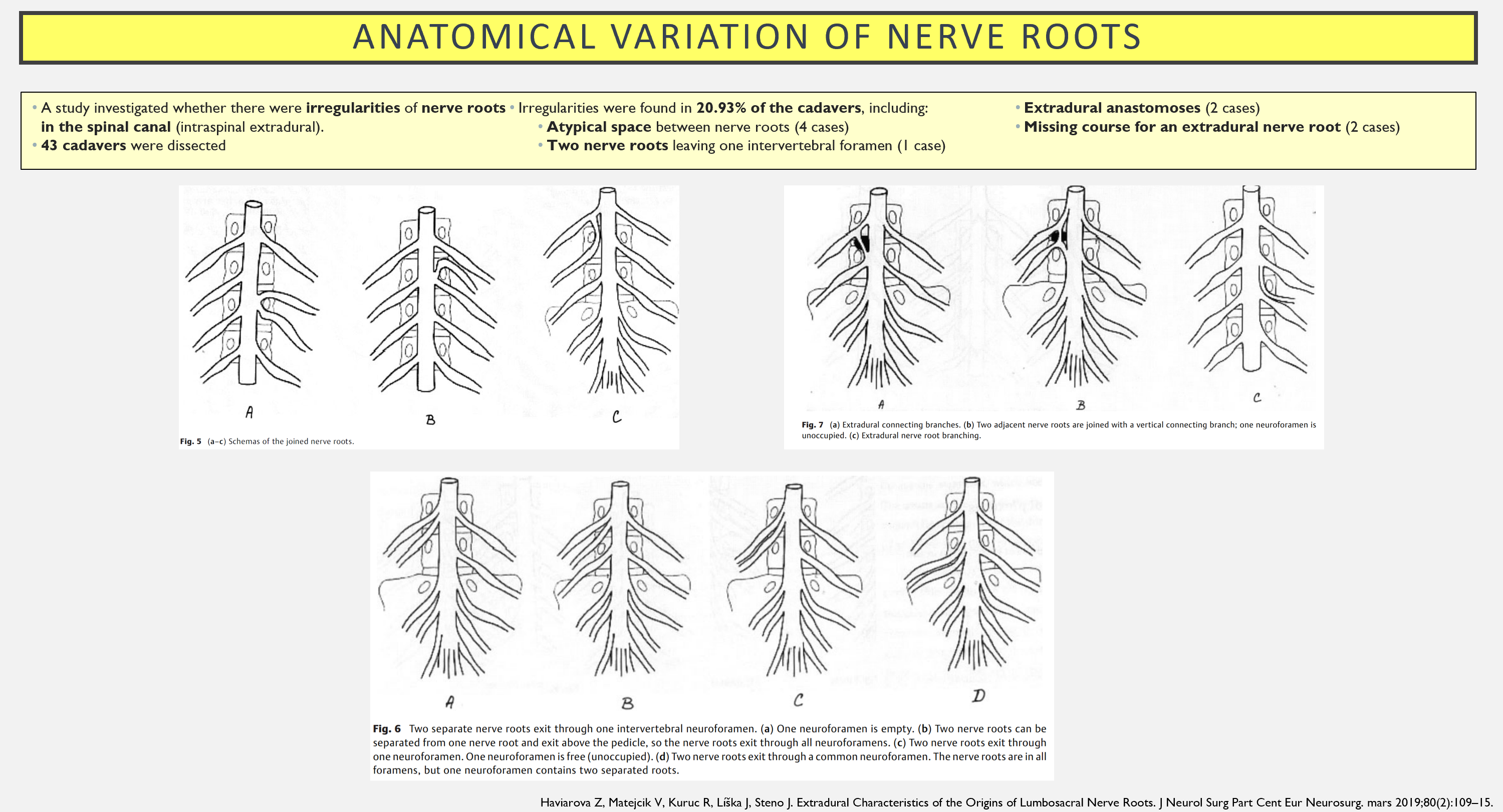

Something that can contribute to variation is anastomoses between the dorsal horns. In one study, it was observed that 22% of lumbar dorsal roots communicated with the neighboring segment via anastomoses (4).

Other anatomical variations may involve a “transitional segment” between the lumbar spine and sacrum. This is not entirely uncommon. This means that the fifth lumbar vertebra is only partially fused with the top of the sacrum. It is not a “pure” lumbar vertebra, and it is not a fixed part of the sacrum—thus a transitional vertebra—a hybrid. In one study, it was found that 5% had 23 vertebrae, while 3% had 25 vertebrae—where 24 is common. These individuals may have differences in dermatome patterns, and the function of the lumbosacral nerve roots may be altered. This was not known when the historical dermatome maps were constructed (17).

Summary

A dermatome is a skin area supplied by a nerve root. Several dermatome maps have been created throughout history. Currently, Lee et al. (2008) dermatome map is the best available. One cannot diagnose the nerve root level based on where the patient has pain (except possibly for S1). There are several reasons for the variation in dermatomes between patients.

References

1. Jansen J. dermatom. I: Store medisinske leksikon [Internett]. 2020 [sitert 4. mars 2021]. Tilgjengelig på: http://sml.snl.no/dermatom

2. Greenberg SA. The history of dermatome mapping. Arch Neurol. januar 2003;60(1):126–31.

3. Jansen J, Holck P. nerverot. I: Store medisinske leksikon [Internett]. 2019 [sitert 4. mars 2021]. Tilgjengelig på: http://sml.snl.no/nerverot

4. Lee MWL, McPhee RW, Stringer MD. An evidence-based approach to human dermatomes. Clin Anat N Y N. juli 2008;21(5):363–73.

5. THORBURN W. THE SENSORY DISTRIBUTION OF SPINAL NERVES. Brain. 1. januar 1893;16(3):355–74.

6. Fleming GWTH. The Dermatomes in Man. (Brain, vol. lvi, March, 1933.) Foerster, O. J Ment Sci. juli 1933;79(326):522–522.

7. Keegan JJ, Garrett FD. The segmental distribution of the cutaneous nerves in the limbs of man. Anat Rec. desember 1948;102(4):409–37.

8. Downs MB, Laporte C. Conflicting Dermatome Maps: Educational and Clinical Implications. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. juni 2011;41(6):427–34.

9. Davis L, Martin J, Goldstein SL. Sensory changes with herniated nucleus pulposus. J Neurosurg. mars 1952;9(2):133–8.

10. Challoumas D, Ferro A, Walker A, Brassett C. Observations on the inconsistency of dermatome maps and its effect on knowledge and confidence in clinical students: Dermatomes in Medical Education. Clin Anat. mars 2018;31(2):293–300.

11. Reiman MP. Orthopedic clinical examination. 2016.

12. Brodal P. Sentralnervesystemet. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2013.

13. Vucetic N, Määttänen H, Svensson O. Pain and pathology in lumbar disc hernia. Clin Orthop. november 1995;(320):65–72.

14. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep [Internett]. 22. juli 2020 [sitert 24. september 2020];5(4). Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7382548/

15. Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, Gerrard JK, Clary R. Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain: Does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? Chiropr Osteopat. 21. september 2009;17:9.

16. Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Tosteson ANA, Zhao W, Morgan TS, Abdu WA, mfl. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: eight-year results for the spine patient outcomes research trial. Spine. 1. januar 2014;39(1):3–16.

17. Furman MB, Johnson SC. Induced lumbosacral radicular symptom referral patterns: a descriptive study. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2019;19(1):163–70.

18. Al Nezari NH, Schneiders AG, Hendrick PA. Neurological examination of the peripheral nervous system to diagnose lumbar spinal disc herniation with suspected radiculopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. juni 2013;13(6):657–74.