Neurodynamic tests are crucial for identifying symptomatic disc herniation with radiculopathy/radicular pain. Have a look at part 1 for introduction.

Straight leg raise

Based on the diagram above, straight leg raise (SLR) and crossed SLR are two reliable tests (1). It’s recommended to test the “healthy” side first, so crossed SLR is always included (2). Dr. Charles Lasègue first described straight leg raise in 1864, hence it’s also called Lasègue’s test (3). I’ve wondered about what to call it myself. According to Cochrane, SLR is the standard test where you only lift the leg straight, while Lasègue’s test involves lifting it until symptoms occur, lowering the leg, and then dorsiflexing the ankle (1). Some call dorsiflexion of the ankle “Bragard’s sign” (4). It’s easy to get confused. Regardless of the name, the most important thing is to perform variations to differentiate (changing how nerve tissue is tensioned/relaxed) and describe it so others can understand.

If you were to rank the importance of neurodynamic tests, SLR is probably the most important. That’s why doctors primarily learn this test, not Slump and femoral nerve stretch test. SLR stretches L5 and S1 nerve roots 2-6 mm caudally, and these two nerve roots are mainly tested (5). Where do most disc herniation occur? Well, 95% of lumbar disc herniation occur in the two lowest levels (6).

SLR/Lasègue

There’s some variation in the literature regarding when the test is positive. One source states that the test is positive when there are radiating pain sensations from the buttocks to below the knee, with the leg positioned between 30 and 70 degrees. There are many sources of error here. What if you have a patient who’s a gymnast or has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and has excellent hamstring/hip flexibility? What if the pain doesn’t radiate below the knee? I’ve had several patients where radicular pain didn’t extend below the knee but still had a positive response to dorsiflexion.

I believe the key is to look at how high you can lift the leg, especially in terms of side-to-side differences, your ability to differentiate, and whether it reproduces the pain.

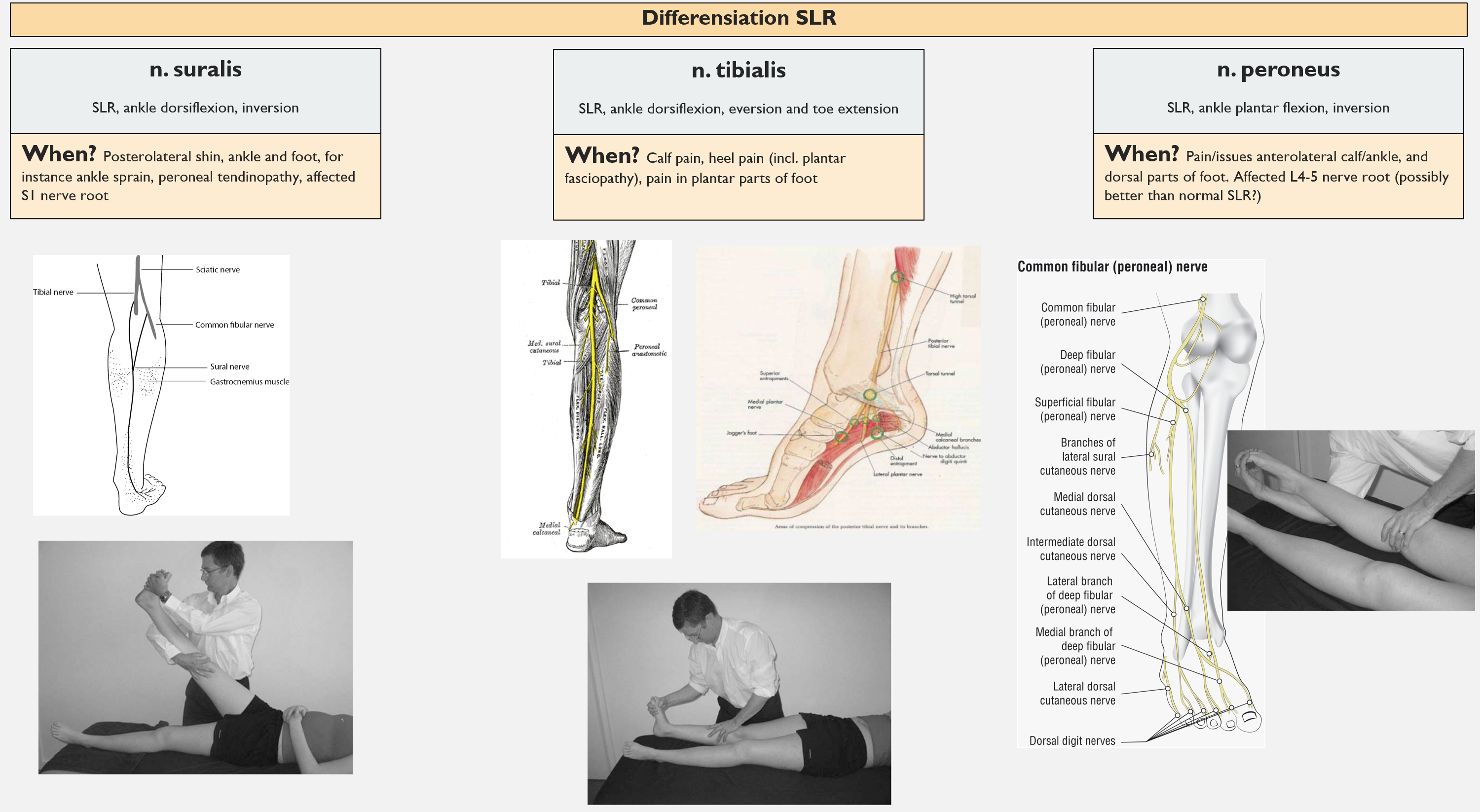

Structural differentiation

There are various ways to differentiate SLR. The most common methods are dorsiflexion of the ankle (Bragard’s sign) and cervical flexion, but internal hip rotation and hip adduction can also be used to further stretch the sciatic nerve (2,4). To put more tension on the tibial nerve, you can perform dorsiflexion and eversion of the ankle, while dorsiflexion and inversion put more tension on the sural nerve. Plantarflexion and inversion extend the peroneal nerves (see image below).

Practical example

If you have a positive SLR and crossed SLR, it’s highly likely there’s involvement of the dura mater, nerve root, or sciatic nerve (4). SLR has high sensitivity, while crossed SLR has high specificity. We know that 90% of cases of radicular leg pain are due to disc herniation. We also know that disc herniations most often occurs in the two lowest lumbar levels, while SLR tests the L5 and S1 nerve roots. Therefore, one can assume a greater likelihood of disc herniation in L4-5 or L5-S1 with involvement of the L5 or S1 nerve root (of course, history and clinical reasoning are most important).

A Negative Test Matters More!

What many don’t consider is that a negative SLR has more diagnostic value than a positive one. SLR has high sensitivity, and a test with high sensitivity is good at detecting a symptomatic disc herniation with radicular pain. A sensitivity of 0.92 means that 92% of patients with lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy are detected with SLR (true positive), while 8% are not (true negative). If the test is negative, there’s a high chance it’s not disc herniation with radicular pain, i.e., it’s good at ruling out disease/illness (SnOUT). If you want to read more on this topic, I recommend David Poulter’s blog.

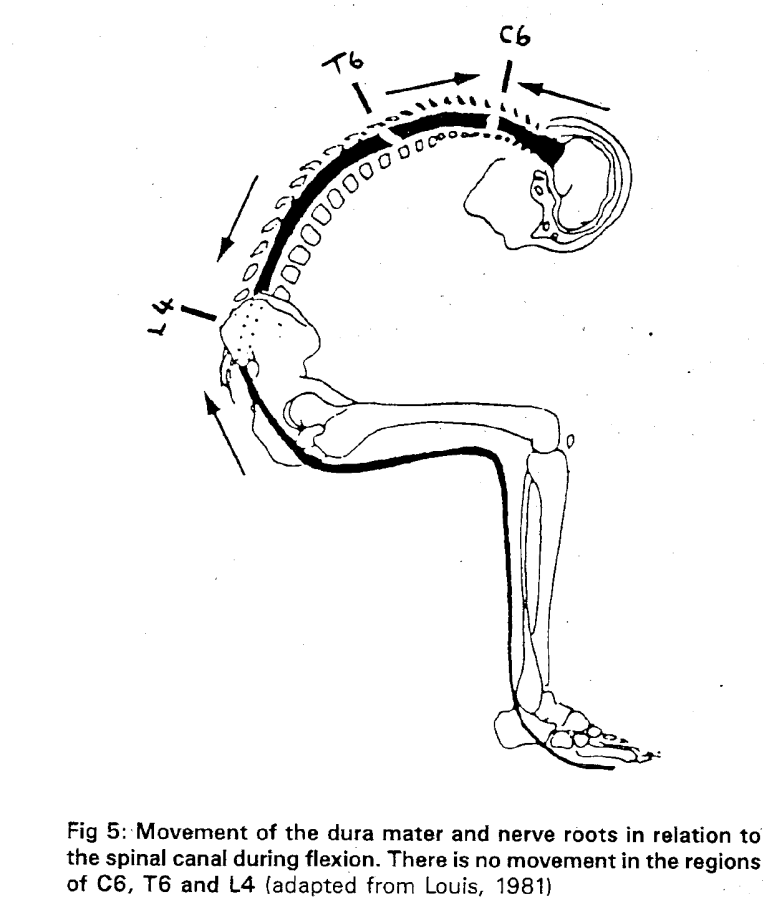

Slump

I also use the slump test in neurological screening tests. The two studies I’ve found on this test show good sensitivity (0.83 and 0.84) but somewhat varying specificity (0.55 and 0.83) (5,7). Therefore it’s good to rule in a potential disc herniation with radicular pain. In Reiman’s view (2), the slump is considered more a test of the entire neurodynamic system, while, as mentioned, SLR tests the two lowest nerve roots (L5-S1) (5). Slump provides a cranial stretch of the spinal cord and thus tests several of the upper lumbar nerve roots (5). It has been suggested that there are certain areas in the spine where there is little sliding between the spinal cord and structures in the back, more like “fixed points,” namely C6, T6, and L4. Typically, it’s best to use neck flexion-extension as differentiation (2). An article suggests that slump is better suited for long-standing problems and suspected canal issues (2). Majlesi et al. (5) suggest it better captures symptomatic disc herniation without nerve root involvement, although, of course, it’s debatable what its significance is. In the lumbar region, you can’t be very specific in diagnosis (85-90% have nonspecific low back pain), and many have disc herniation without back pain (8–10).

Femoral nerve stretch test, aka “prone knee bend” and “slump knee bend”

To test for the presence of disc herniation with nerve root involvement in the L2-L4 region, a neurodynamic test of the femoral nerve can be performed. Wassermann developed this test in 1918 to examine soldiers experiencing pain in the front of the thigh and calf, along with a negative SLR (straight leg raise) test (11). The femoral nerve originates from the nerve roots L1-L4 (12), and it’s necessary to stretch the front of the thigh to assess these structures. This test goes by various names and can be performed in different ways. There isn’t much research on this test, and there are no meta-analyses or systematic reviews available.

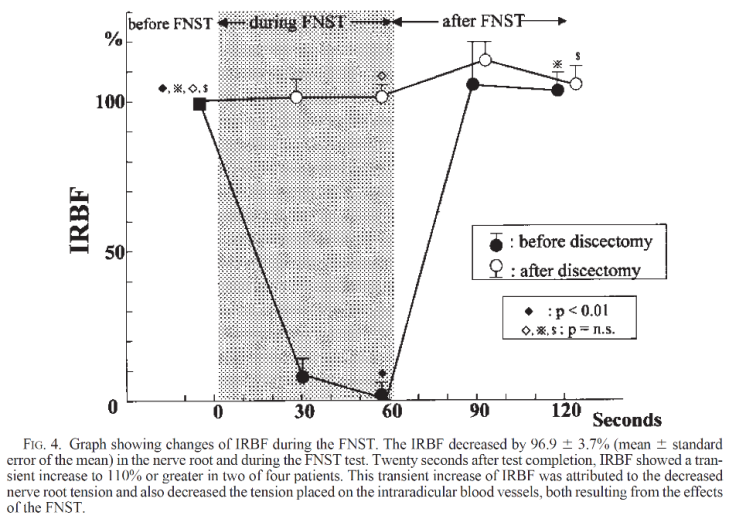

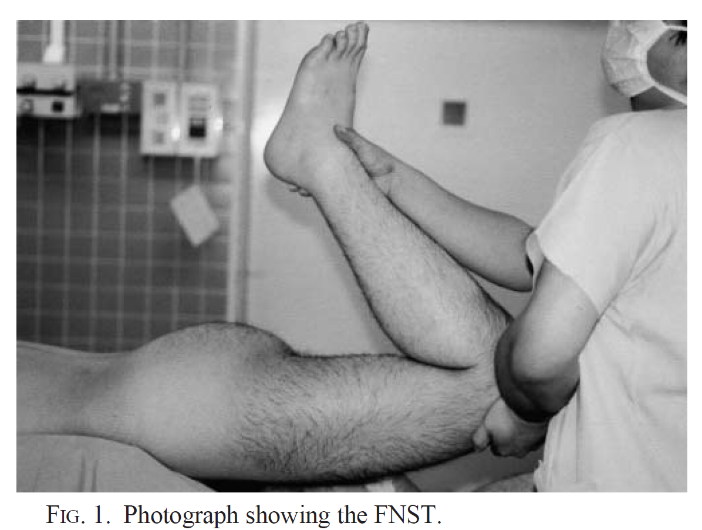

A small yet valuable study (13) demonstrated that the prone knee bend version of this test had moderate sensitivity (0.50) but excellent specificity (1.00) for detecting nerve root involvement in L2-L4 when examined through MRI. So, if the test is positive, there’s a significant likelihood of nerve root involvement in L2, L3, and/or L4 (13). Patients who underwent surgery for disc herniation between L3 and L4 were also tested. They observed no nerve root sliding (due to disc herniation) during the stretch of the femoral nerve. However, after discectomy, there was 3-4 mm of sliding. They also noticed that stretching the femoral nerve resulted in a near cessation of intraradicular blood flow before the surgery, but it returned to normal after the operation (14) (see the image below). One week after the surgery, all tests were negative for femoral nerve stretch.

Another version of femoral nerve stretch that I believe should be highlighted is the side-lying femoral nerve stretch (slump knee bend). In a study, this test correctly identified all four patients with nerve root involvement of L2-L4 (100% sensitivity) but had two false positives (83% specificity), resulting in a +LR of 6.0 (15). The advantage of this test is that you can easily differentiate/increase tension by performing neck flexion, which can be challenging in the prone position. The back is also in a stabile position.

It may be somewhat challenging to determine what constitutes a positive test in this case. If there’s increased secondary hyperalgesia, many things can be painful, and there may be an uncomfortable stretch in the front of the thigh, regardless of whether there is nerve root involvement. With the slump knee bend, it’s suggested that the starting position is with neck flexion, and a positive test should lead to the disappearance of pain in the back/thigh upon neck extension (15). Alternatively, you can move to the extreme position of hip/knee, then extend the neck to see if you can further stretch the leg backward. Thus, the neck plays a vital role in this test.

In one study, it was suggested that full hip extension and knee flexion were necessary for the nerve root to be further compressed during testing (see the image) (14). This leads me to another topic. During our studies, we learned that, for instance, we could perform the slump test with an extended position in the back, especially in cases of foraminal stenosis. Would it be wise to narrow down the area where the nerve glides before the test is performed? I’m not sure, but it’s possible that it could be beneficial to “provoke” a bit of increased mechanosensitivity.

There are several case reports that also discuss the importance of the “crossed femoral nerve stretch” in diagnosis (16,17).

Other variants

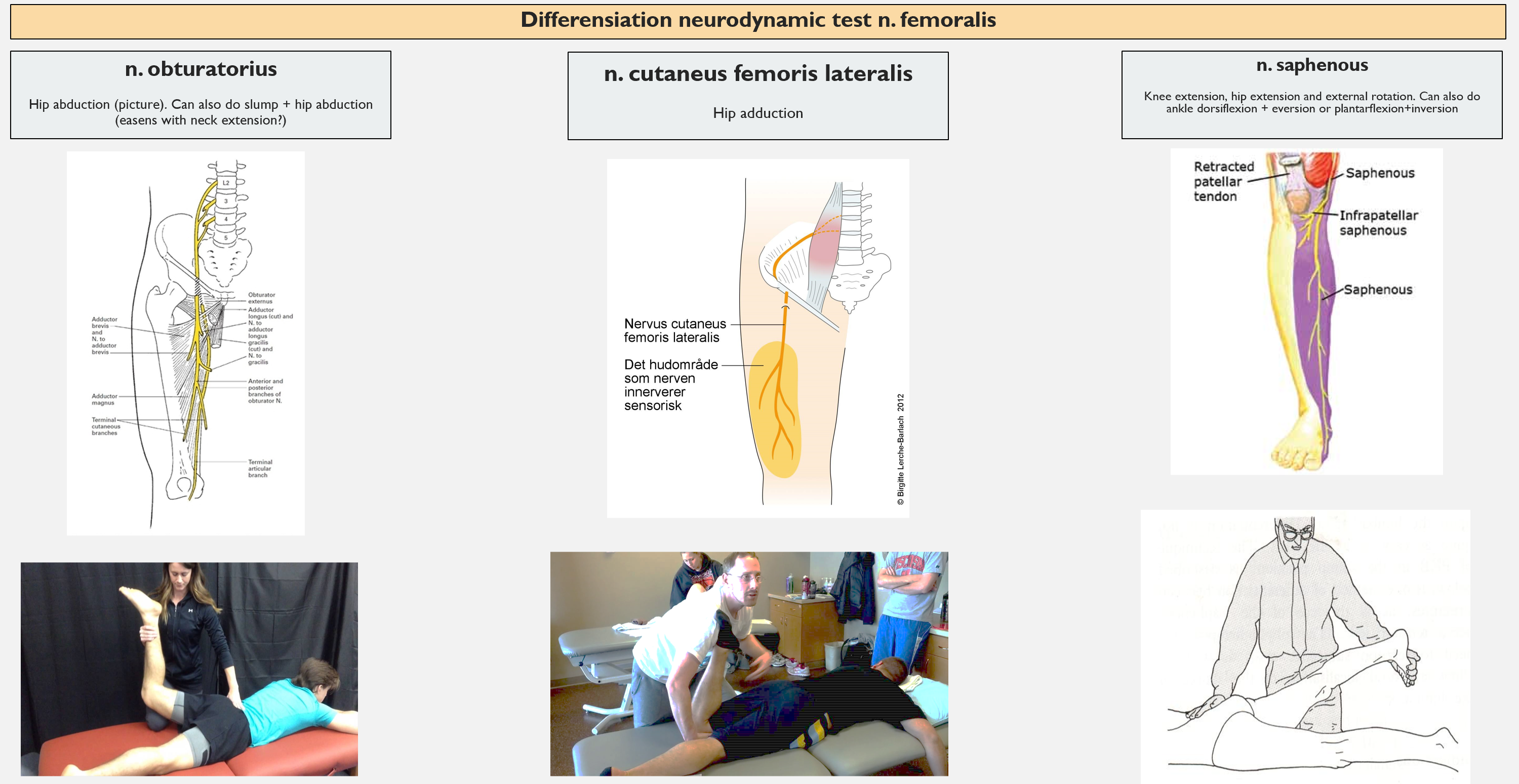

You can perform the “prone knee bend” with hip abduction to put more stretch on the obturator nerve and adduction for more stretch on the cutaneous femoris lateralis nerve (in cases of meralgia paraesthetica).

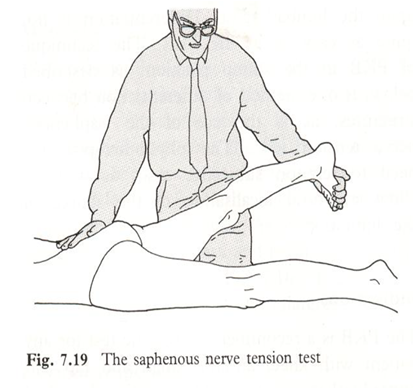

The femoral nerve also transitions into the saphenous nerve, where it travels medially behind the axis of the knee. The saphenous nerve is slack in the prone knee bend. To test it, the knee should be extended, the hip should be extended and externally rotated. You can also add eversion and dorsiflexion or plantarflexion and inversion.

Summary of differentiating femoral nerve stretches:

Summary

The Straight Leg Raise (SLR) test is the most important neurodynamic test because it evaluates the two lowest nerve roots, and 95% of disc herniations occur in the two lowest levels. The slump test is a useful complement. It can also be a good idea to perform a neurodynamic test of the femoral nerve. There are various variations to further stretch different nerve tissues.

References

1. van der Windt DA, Simons E, Riphagen II, Ammendolia C, Verhagen AP, Laslett M, mfl. Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 17. februar 2010;(2):CD007431.

2. Reiman MP. Orthopedic clinical examination. 2016.

3. Scaia V, Baxter D, Cook C. The pain provocation-based straight leg raise test for diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation, lumbar radiculopathy, and/or sciatica: a systematic review of clinical utility. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2012;25(4):215–23.

4. Solberg AS, Kirkesola G. Klinisk undersøkelse av ryggen. Kristiansand: HøyskoleForlaget; 2007.

5. Majlesi J, Togay H, Ünalan H, Toprak S. The Sensitivity and Specificity of the Slump and the Straight Leg Raising Tests in Patients With Lumbar Disc Herniation: JCR J Clin Rheumatol. april 2008;14(2):87–91.

6. Jordan J, Konstantinou K, O’Dowd J. Herniated lumbar disc. BMJ Clin Evid. 26. mars 2009;2009.

7. Stankovic R, Johnell O, Maly P, Willner S. Use of lumbar extension, slump test, physical and neurological examination in the evaluation of patients with suspected herniated nucleus pulposus. A prospective clinical study. Man Ther. februar 1999;4(1):25–32.

8. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, mfl. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet Lond Engl. 09 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

9. O’Sullivan P. It’s time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med. mars 2012;46(4):224–7.

10. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, mfl. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. Am J Neuroradiol. april 2015;36(4):811–6.

11. Estridge MN, Rouhe SA, Johnson NG. The femoral stretching test. A valuable sign in diagnosing upper lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. desember 1982;57(6):813–7.

12. Holck P. lumbalnervefletningen. I: Store medisinske leksikon [Internett]. 2019 [sitert 2. april 2020]. Tilgjengelig på: http://sml.snl.no/lumbalnervefletningen

13. Suri P, Rainville J, Katz JN, Jouve C, Hartigan C, Limke J, mfl. The accuracy of the physical examination for the diagnosis of midlumbar and low lumbar nerve root impingement. Spine. 1. januar 2011;36(1):63–73.

14. Kobayashi S, Suzuki Y, Asai T, Yoshizawa H. Changes in nerve root motion and intraradicular blood flow during intraoperative femoral nerve stretch test. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. oktober 2003;99(3 Suppl):298–305.

15. Trainor K, Pinnington MA. Reliability and diagnostic validity of the slump knee bend neurodynamic test for upper/mid lumbar nerve root compression: a pilot study. Physiotherapy. mars 2011;97(1):59–64.

16. Nadler SF, Malanga GA, Stitik TP, Keswani R, Foye PM. The crossed femoral nerve stretch test to improve diagnostic sensitivity for the high lumbar radiculopathy: 2 case reports. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. april 2001;82(4):522–3.

17. Kreitz BG, Côté P, Yong-Hing K. Crossed femoral stretching test. A case report. Spine. 1. juli 1996;21(13):1584–6.