(yes, we agreed to call it radicular pain and radiculopathy (see article), but sciatica is so much shorter to write in a heading).

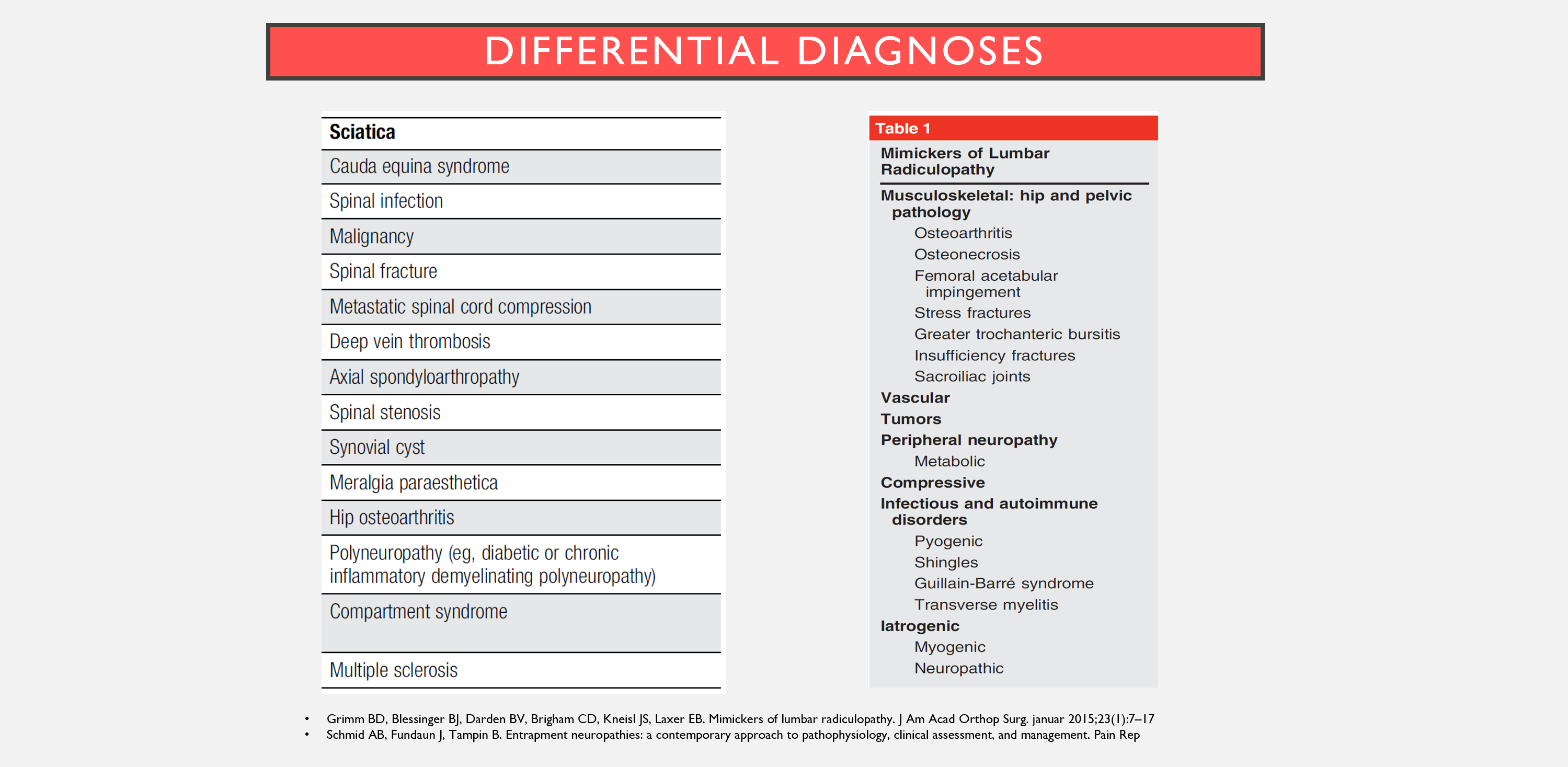

If you have a patient with back pain and radiating pain down the leg, it is important to conduct a thorough medical history and a clinical examination, especially important to determine if there are signs of radiculopathy. In about 90% of cases with lumbar radiculopathy, the cause is disc herniation with nerve root involvement (1,2). Differential diagnoses for this could be (3):

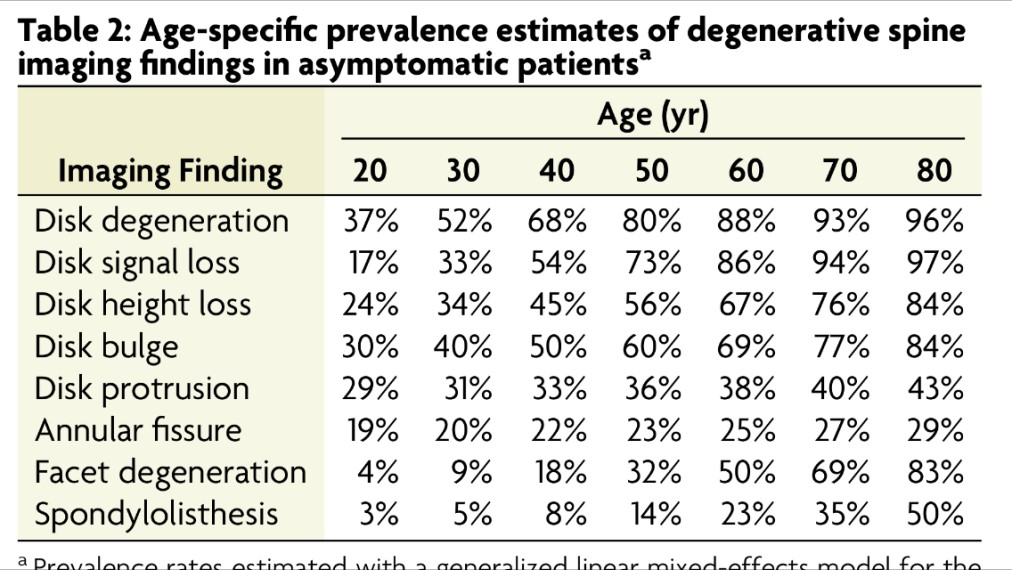

This article will primarily focus on symptomatic disc herniations with nerve root involvement. We know, many (around 1/3) have disc herniation in the lower back without pain (5). Additionally, compression of the nerve seen on an MRI can be asymptomatic (6). But sometimes the tissues matter, and a disc herniation can be the cause of back and leg pain. Knowing more about it makes it easier to diagnose!

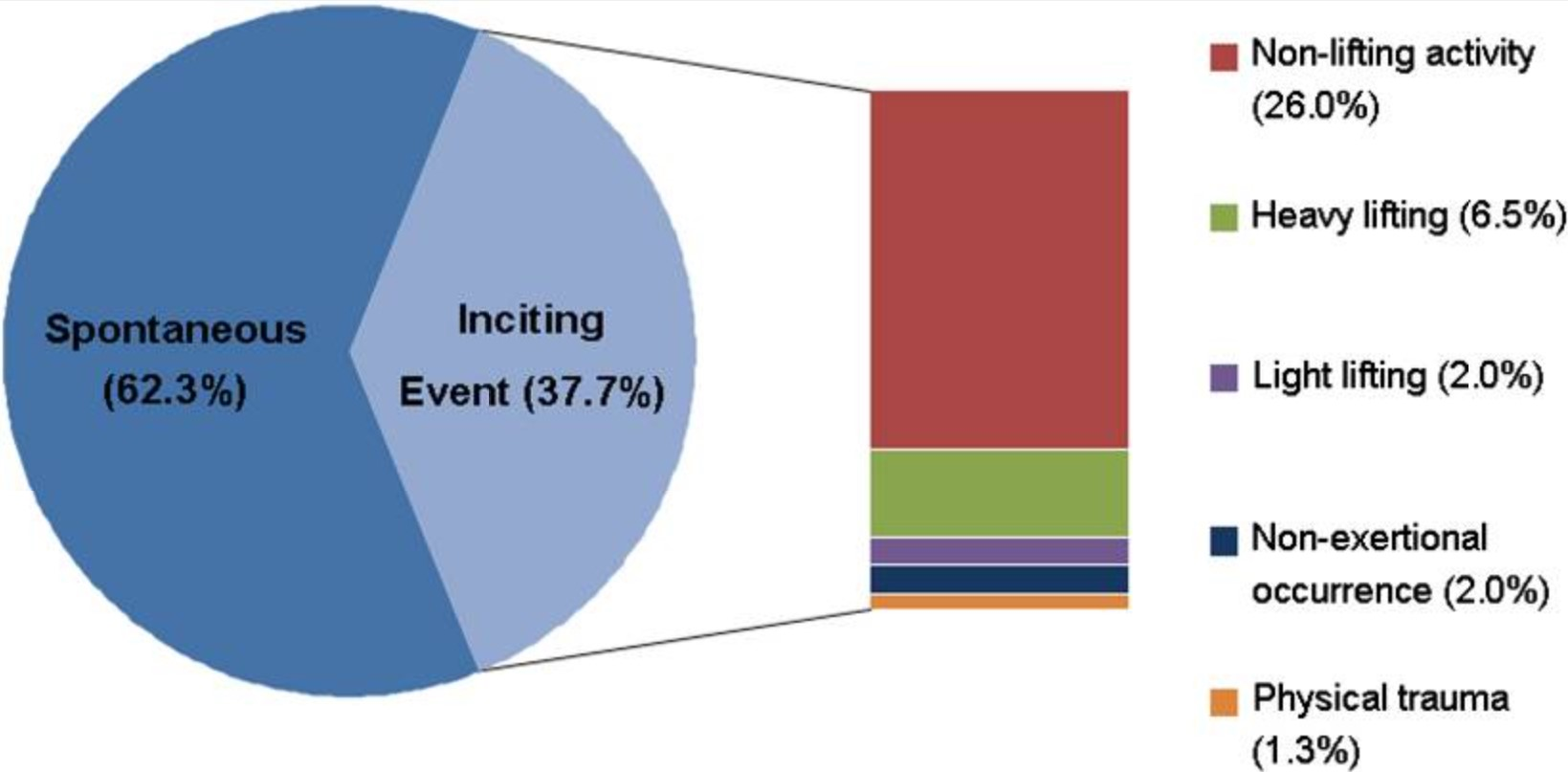

Triggering cause?

A symptomatic disc herniation does not necessarily have an acute onset. A mentor once told me, “If the patient experiences sudden, shooting pain within a ‘millisecond’ during, for example, a lift, then it is less likely to be a disc herniation.” I find this to align well with what I see in the clinic. The disc material doesn’t necessarily “spurt” out into the spinal canal and immediately cause acute pain. It can take time to develop, and the pain might occur a few hours after a triggering activity. Alternatively, the patient might wake up one morning with leg and back pain, without having done anything special. In a study, patients with confirmed disc herniation and nerve root involvement were asked what they believed triggered their pain. Around 2/3 had no clear idea about a cause, while most in the other group believed it originated from everyday activities without lifting (7).

Characteristics

A patient with symptomatic disc herniation will typically have back pain and leg pain, with leg pain often being worse (8,9). Many experience more pain when sitting and bending forward, such as when tying shoelaces, getting dressed, and picking something up from the floor (10). Almost all (95%) of disc herniations in the lower back occur in the two lowest discs in the lower back, L4/L5 and L5/S1. Patients are typically between 30-50 years old, and the ratio between men and women is 2:1. Disc herniation above these two lower discs is more common in those over 55 years old (11). This can result in what a therapist I know called “old man sciatica” – a somewhat fitting but not very pedagogical description.

Back pain?

Many with disc herniation experience an aching pain in the upper iliosacral and/or L5-S1 area. However, one can have radicular pain and disc herniation without back pain (2). Increased pain in the back or leg when coughing, sneezing, or during other forms of Valsalva maneuvers increases suspicion of symptomatic disc herniation (2).

Leg pain?

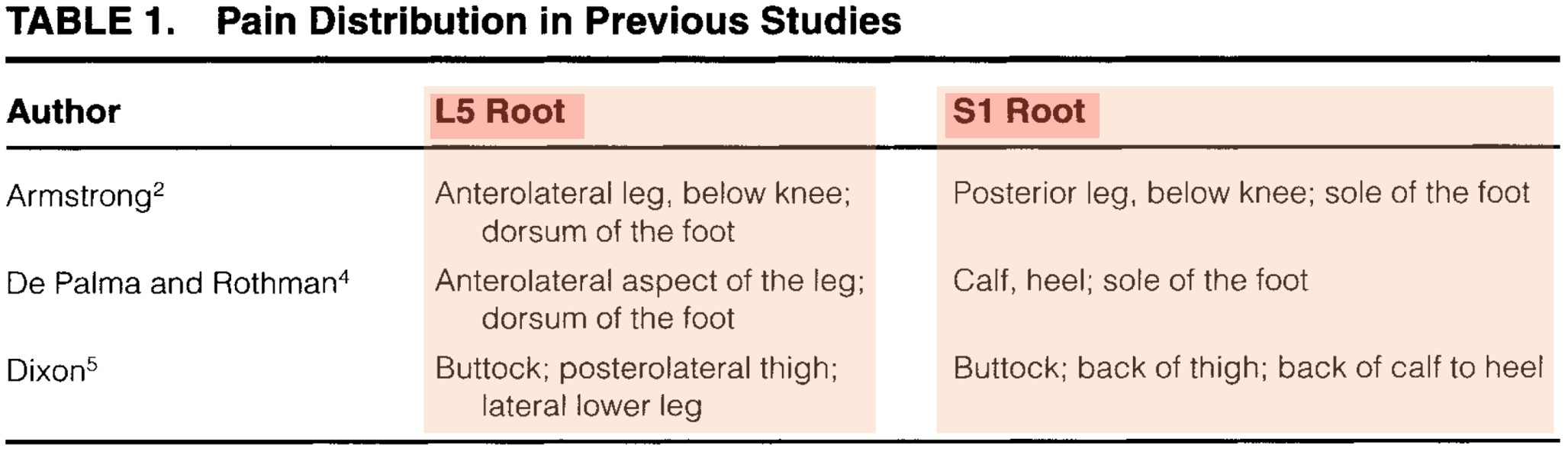

The pain radiating down the leg is typically described as a penetrating, electric, burning, and/or stabbing sensation (12). Some of the patients I see believe they’ve strained their hamstrings and calf! They might experience leg pain when walking quickly, as the long stride stretches the sciatic nerve. According to a source, L4 irritation can cause pain anterolaterally on the thigh, L5 nerve root irritation causes pain dorsolaterally in the thigh, and posterior thigh pain results from S1 irritation (8). Other studies also indicate that differences between L5 and S1 involvement can be recognized, as shown below (13). L5 involvement typically causes pain in the anterolateral leg and dorsum of the foot, while S1 involvement causes pain in the posterior leg and sole of the foot (13).

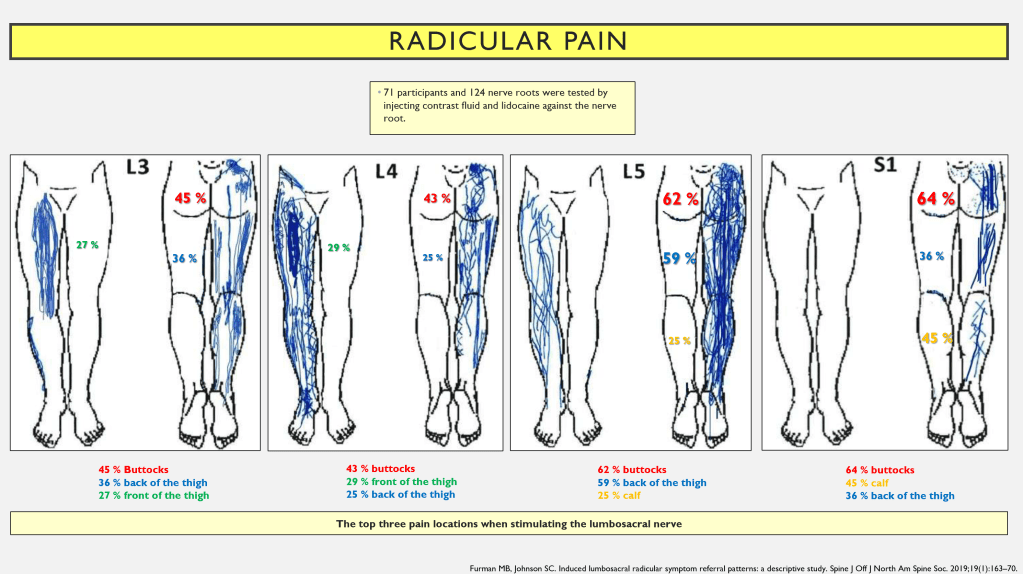

However, this pattern doesn’t always hold true. Pain outside the dermatome has been observed in up to 64-70% of cases with radicular pain (3). One study found that in most cases, pain did not follow a dermatome, except for S1 nerve root pain, which often followed the S1 dermatome (14). Another study (15) stimulated nerve roots by injecting contrast fluid and lidocaine in the area and then registering the location of pain. They found that pain was most commonly reported in the buttock area, whether L3, L4, L5, or S1 was stimulated. After that, there was some variation. It’s possible to say that there’s somewhat more pain in the front of the thigh with L3 and L4 irritation, while there isn’t as much pain in the front of the thigh with L5 and S1 irritation. The conclusion is that you cannot determine the level of nerve root involvement based on where the patient feels pain (except separate between S1?) (14) (see image below).

I’ve seen cases where it’s stated in the medical record that ‘nerve root involvement is excluded since the patient has non-dermatomal pain.’ This is where clinical reasoning can stumble. For instance, it’s been shown that there are often pains in areas other than the hands in carpal tunnel syndrome (16).

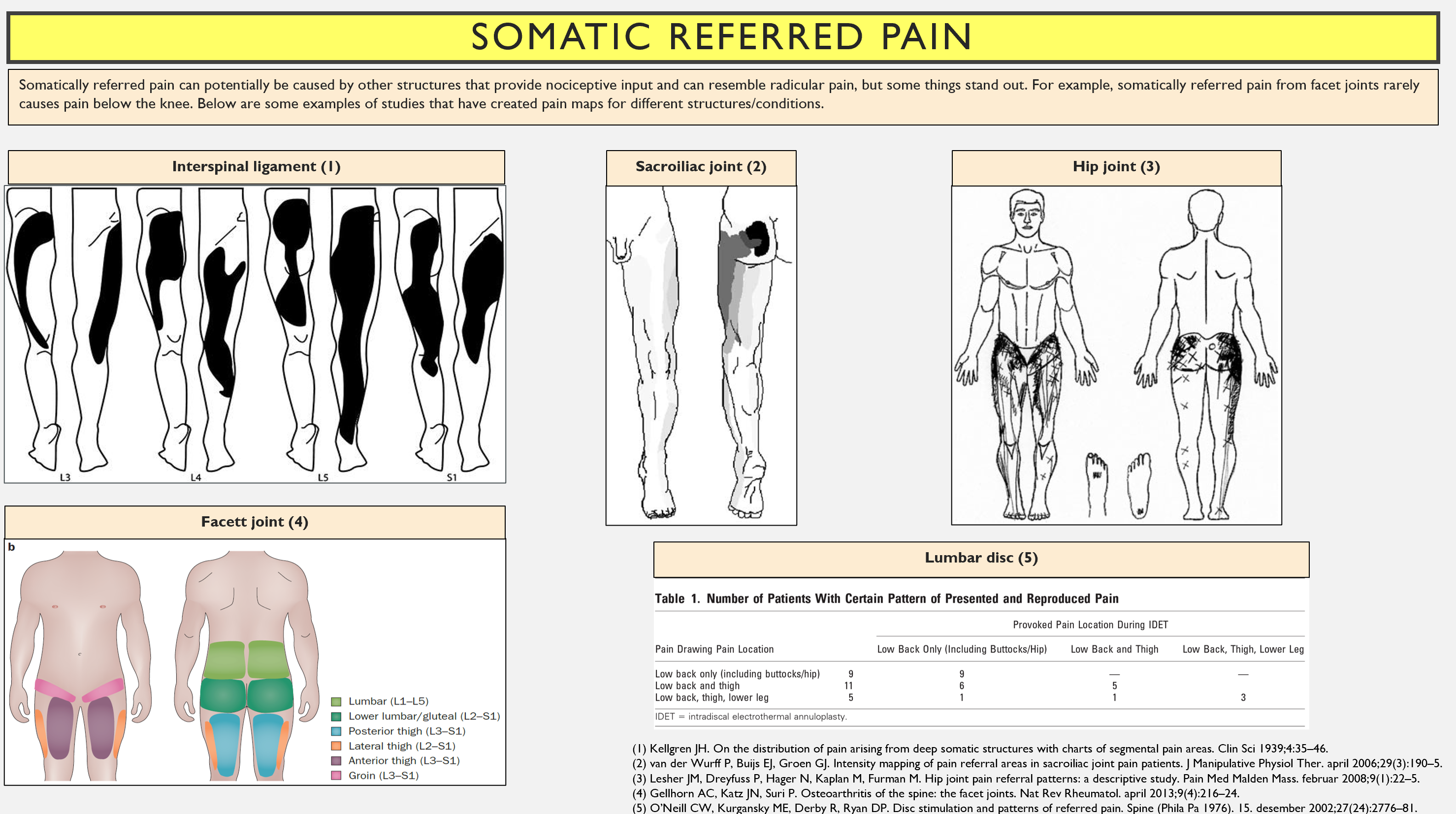

Somatic referred pain

As we know, it’s quite challenging to distinguish the level of disc herniation based on the radicular pain pattern (except for S1?) (15). To make matters more complicated, other issues can also cause radiating pain down the leg, known as somatic referred pain (12). For example, hip joints, iliosacral joints, and facet joints can all provide nociceptive input that results in somatically referred pain down the leg, as seen in the image.

I’ve had patients with really painful leg pain, who looked a little bit like radicular pain, but it showed to be sacroilitis and axial spondyloarthritis. A thorough clinical examination can help differentiate between somatically referred pain and radicular pain.

Nerve function

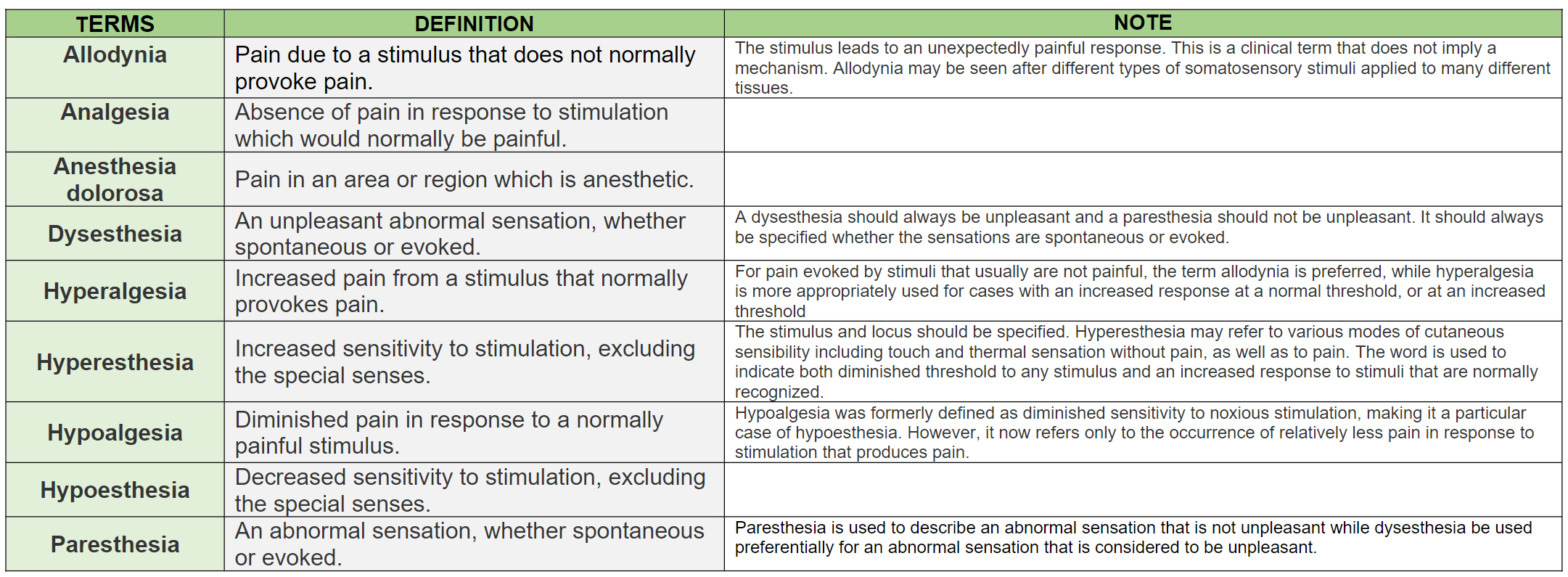

I used to think that there must be impaired nerve function for there to be disc herniation with nerve root involvement, but now I also know that increased function is often present (3) (Anina Schmid talks about ‘gain of function’ and ‘loss of function’). Decreased function shows what are called negative symptoms, while increased function shows what are called positive symptoms (17). Please use the chart below if you’re uncertain about the definitions, taken from IASP (18).

Negative symptoms

Negative symptoms are what one usually tests for in a neurological assessment, namely decreased strength, decreased sensation, and reduced reflexes. This results from a reduction in the conduction of action potentials (3). Patients will typically report that they ‘feel like they’re walking on cotton,’ ‘have lost sensation in the foot,’ or that they ‘have lost control of the leg’ / ‘have become weak in the foot.’

Positive symptoms

Positive symptoms are an increased response to stimuli, including pain from non-painful stimuli (allodynia), increased pain response to normally painful stimuli (hyperalgesia), paresthesia/dysesthesia (tingling/pricking, itching, electric sensations), spontaneous electric shock-like sensations (3,19,20).

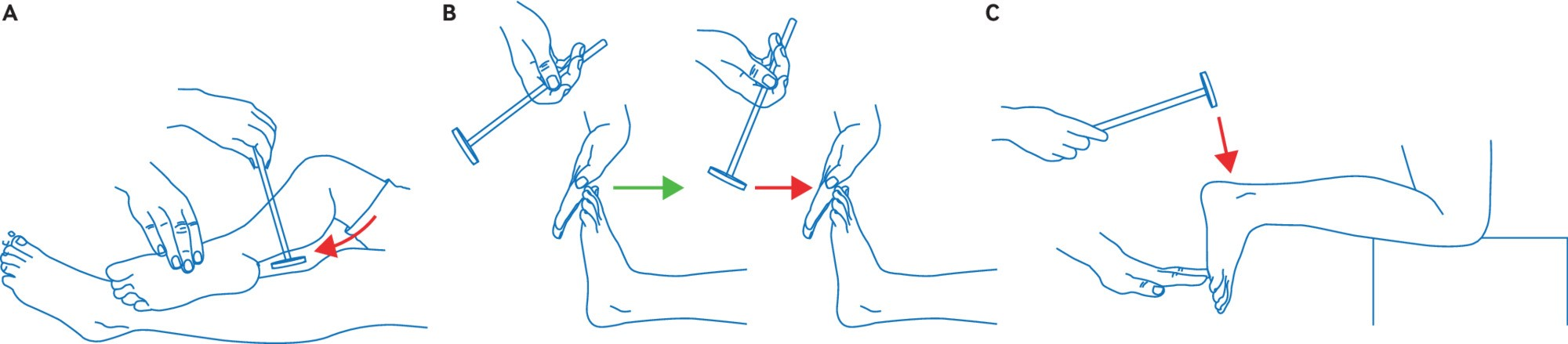

Another sign of increased function is increased mechanosensitivity, as shown in the nerve tension test (3). A small note is that a positive nerve tension test doesn’t necessarily indicate nerve root involvement (false positive), and conversely, a nerve tension test can be negative even when there is nerve root involvement (false negative) (19,22).

Pain drivers

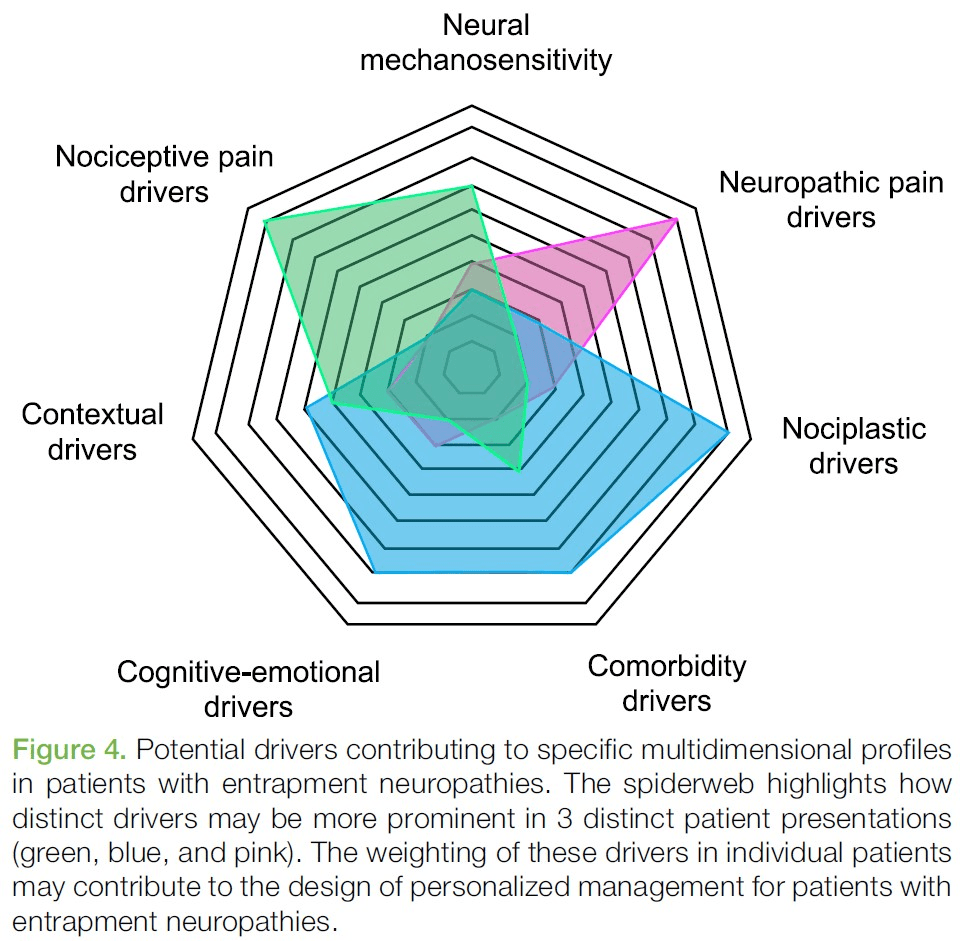

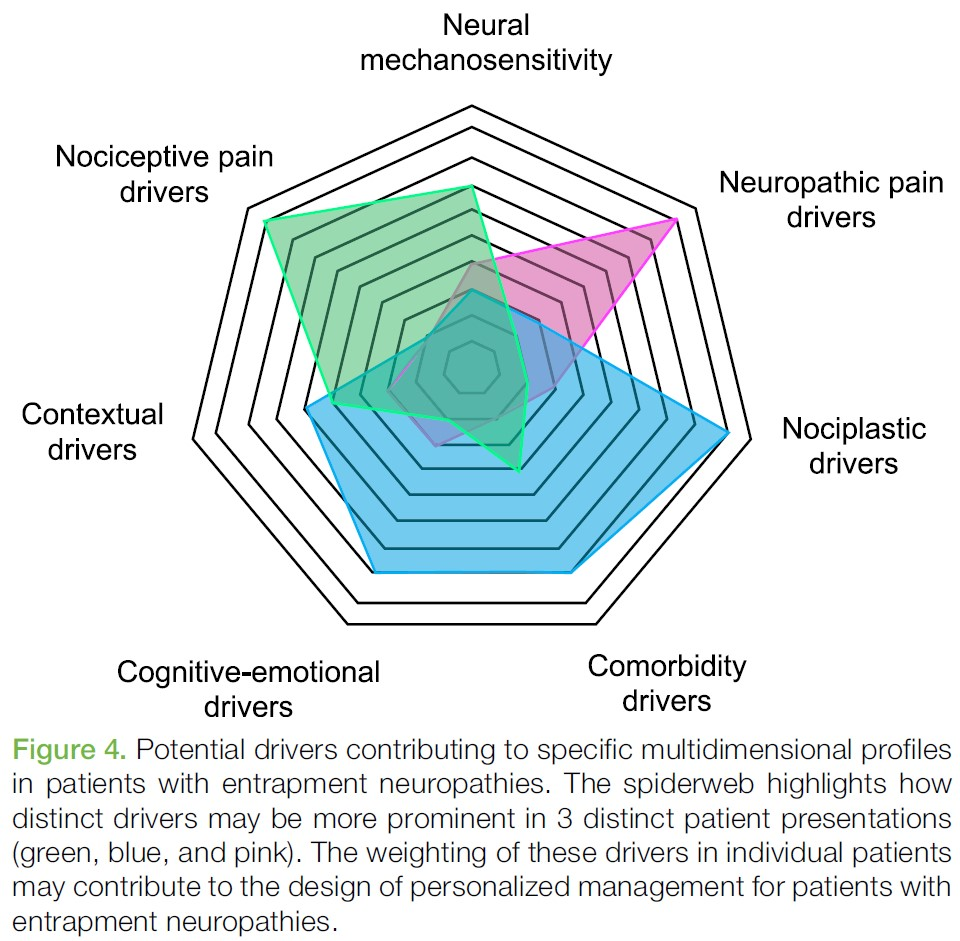

Even though a disc herniation might be considered a biomedical diagnosis, it’s understood that other factors are important for pain, functional level, and prognosis. Therefore, it’s important to explore beliefs and thoughts about the issues, cognitive-emotional factors, social factors, sleep, physical activity, etc. A condition that starts with a greater degree of neuropathic/nociceptive drivers can eventually transition to have a greater degree of nociplastic characteristics. For example, central sensitization is associated with pain that is disproportionate and long-lasting (19). See the graph on potential drivers below, from Schmid et al. (3).

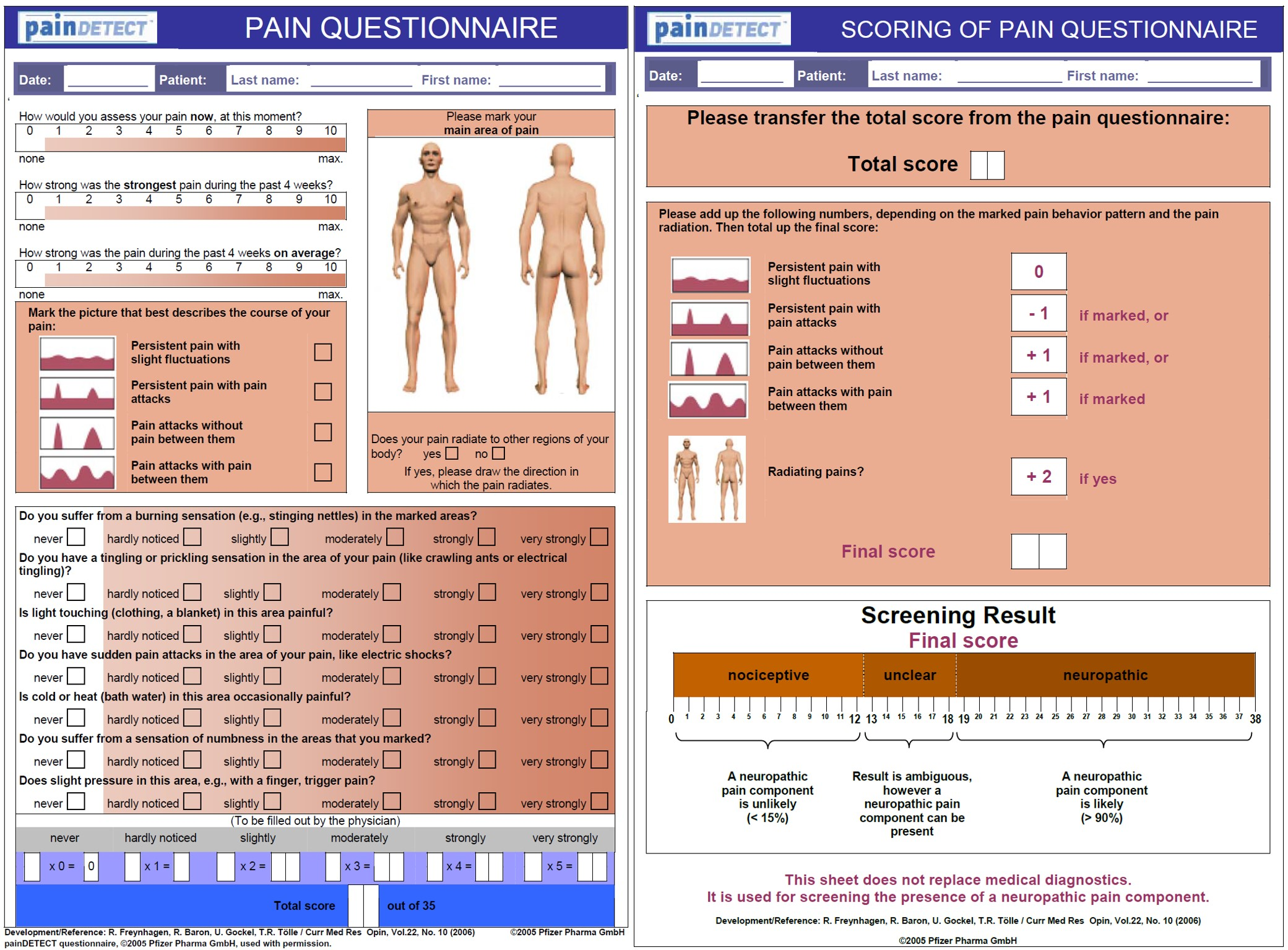

Questionnaire

If there’s uncertainty about the proportion of the pain picture attributable to neuropathic pain drivers, a questionnaire can be used. The PainDETECT Questionnaire is a tool that can be used to identify neuropathic pain in patients with lower back pain (23). The English version has good reliability but uncertain validity (24).

Summary

There isn’t necessarily a clear triggering movement/activity for disc herniation with radicular pain/lumbar radiculopathy (and as we’ll return to later, genetics have more influence than initially thought, and strain is of lesser significance). Leg pain is often worse than back pain. You cannot diagnose the level of nerve root involvement based solely on the area of pain, except possibly for S1. In cases of nerve root involvement, you can experience both negative and positive symptoms. Although one might view disc herniation with nerve root involvement as a biomedical diagnosis, this can also be influenced by other factors – becoming more nociplastic in nature. Therefore, it’s important to also take a thorough psychosocial history (but it is uncertain / disputed whether psychosocial factors affect the prognosis of conservative treatment for patients with radicular pain).

References

1. Iversen T. Lumbosacral radiculopathy managed in multidisciplinary back clinics. Diagnostic accuracy, prognostic factors and efficacy of epidural injection therapy. [PHD]. UiT Norges arktiske universitet; 2015.

2. Ropper AH, Zafonte RD. Sciatica. N Engl J Med. 26. mars 2015;372(13):1240–8.

3. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep [Internett]. 22. juli 2020 [sitert 24. september 2020];5(4). Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7382548/

4. Grimm BD, Blessinger BJ, Darden BV, Brigham CD, Kneisl JS, Laxer EB. Mimickers of lumbar radiculopathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. januar 2015;23(1):7–17.

5. Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, mfl. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. Am J Neuroradiol. april 2015;36(4):811–6.

6. O’Neill S, Jaszczak SLT, Steffensen AKS, Debrabant B. Using 4+ to grade near-normal muscle strength does not improve agreement. Chiropr Man Ther [Internett]. 10. oktober 2017 [sitert 14. november 2020];25. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5633899/

7. Suri P, Hunter DJ, Jouve C, Hartigan C, Limke J, Pena E, mfl. Inciting Events Associated with Lumbar Disk Herniation. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. mai 2010;10(5):388–95.

8. Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 23. juni 2007;334(7607):1313–7.

9. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, mfl. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet Lond Engl. 09 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

10. Amin RM, Andrade NS, Neuman BJ. Lumbar Disc Herniation. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 4. oktober 2017;10(4):507–16.

11. Jordan J, Konstantinou K, O’Dowd J. Herniated lumbar disc. BMJ Clin Evid. 26. mars 2009;2009.

12. Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 15. desember 2009;147(1–3):17–9.

13. Vucetic N, Määttänen H, Svensson O. Pain and pathology in lumbar disc hernia. Clin Orthop. november 1995;(320):65–72.

14. Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, Gerrard JK, Clary R. Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain: Does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? Chiropr Osteopat. 21. september 2009;17:9.

15. Furman MB, Johnson SC. Induced lumbosacral radicular symptom referral patterns: a descriptive study. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2019;19(1):163–70.

16. Schmid AB, Nee RJ, Coppieters MW. Reappraising entrapment neuropathies–mechanisms, diagnosis and management. Man Ther. desember 2013;18(6):449–57.

17. Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, mfl. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 16. februar 2017;3:17002.

18. IASP Terminology – IASP [Internett]. [sitert 29. november 2020]. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.iasp-pain.org/terminology?navItemNumber=576#Allodynia

19. Schmid AB, Tampin B. Section 10, Chapter 10: Spinally Referred Back and Leg Pain – International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. I: Boden SD, redaktør. Lumbar Spine Online Textbook [Internett]. 2020 [sitert 4. oktober 2020]. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.wheelessonline.com/ISSLS/section-10-chapter-10-spinally-referred-back-and-leg-pain/

20. Baron R, Binder A, Attal N, Casale R, Dickenson AH, Treede R-D. Neuropathic low back pain in clinical practice. Eur J Pain Lond Engl. 2016;20(6):861–73.

21. Helseth E, Harbo HF, Rootwelt T. Nevrologi og nevrokirurgi. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2019.

22. Schmid AB, Hailey L, Tampin B. Entrapment Neuropathies: Challenging Common Beliefs With Novel Evidence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):58–62.

23. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. oktober 2006;22(10):1911–20.

24. Tampin B, Bohne T, Callan M, Kvia M, Melsom Myhre A, Neoh EC, mfl. Reliability of the English version of the painDETECT questionnaire. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(4):741–8.