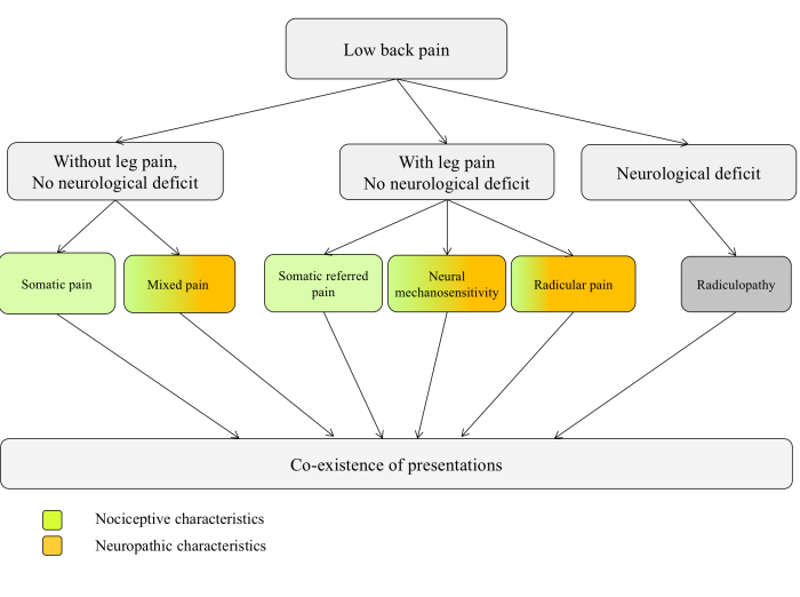

As mentioned in the previous post, there is a distinction between radicular pain, radiculopathy, and somatic referred pain. This post aims to delve into radiculopathy.

What is radiculopathy?

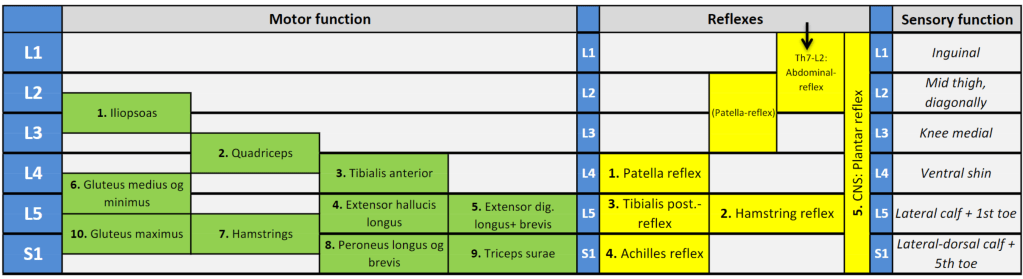

Radiculopathy occurs when a disc herniation presses/pulls on a nerve root, leading to impaired nerve function. The nerve conduction is blocked (1)! This is characterized by muscle weakness, decreased sensibility, and/or loss of reflexes (2). Neurological diagnostic tests must be conducted to determine whether radiculopathy is present.

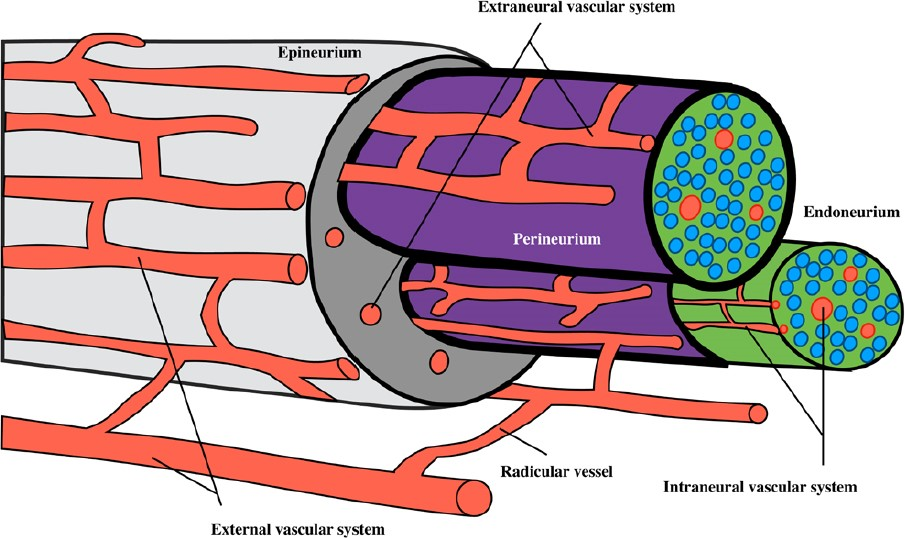

Nerve tissue is particularly susceptible to compression-induced hypoxia, as nerve tissue is the body’s most oxygen-demanding tissue (4). Nerves often have thicker supportive tissue where they run along bones and joints to provide better protection. Nerve roots lack the two outermost support layers (epineurium and perineurium), which may make them more susceptible to injury (5).

What Is Required to Cause Radiculopathy?

The magnitude of pressure, the duration of pressure, and the type of pressure are crucial factors in determining whether nerve damage will occur. Pressure can be either uniform or lateral. Uniform pressure is when the pressure is evenly distributed around the nerve, as in carpal tunnel syndrome, while lateral pressure occurs when the nerve is caught between two surfaces, as in disc herniation in the intervertebral foramen (5). Here is an example of lateral pressure affecting two nerves of different sizes (6):

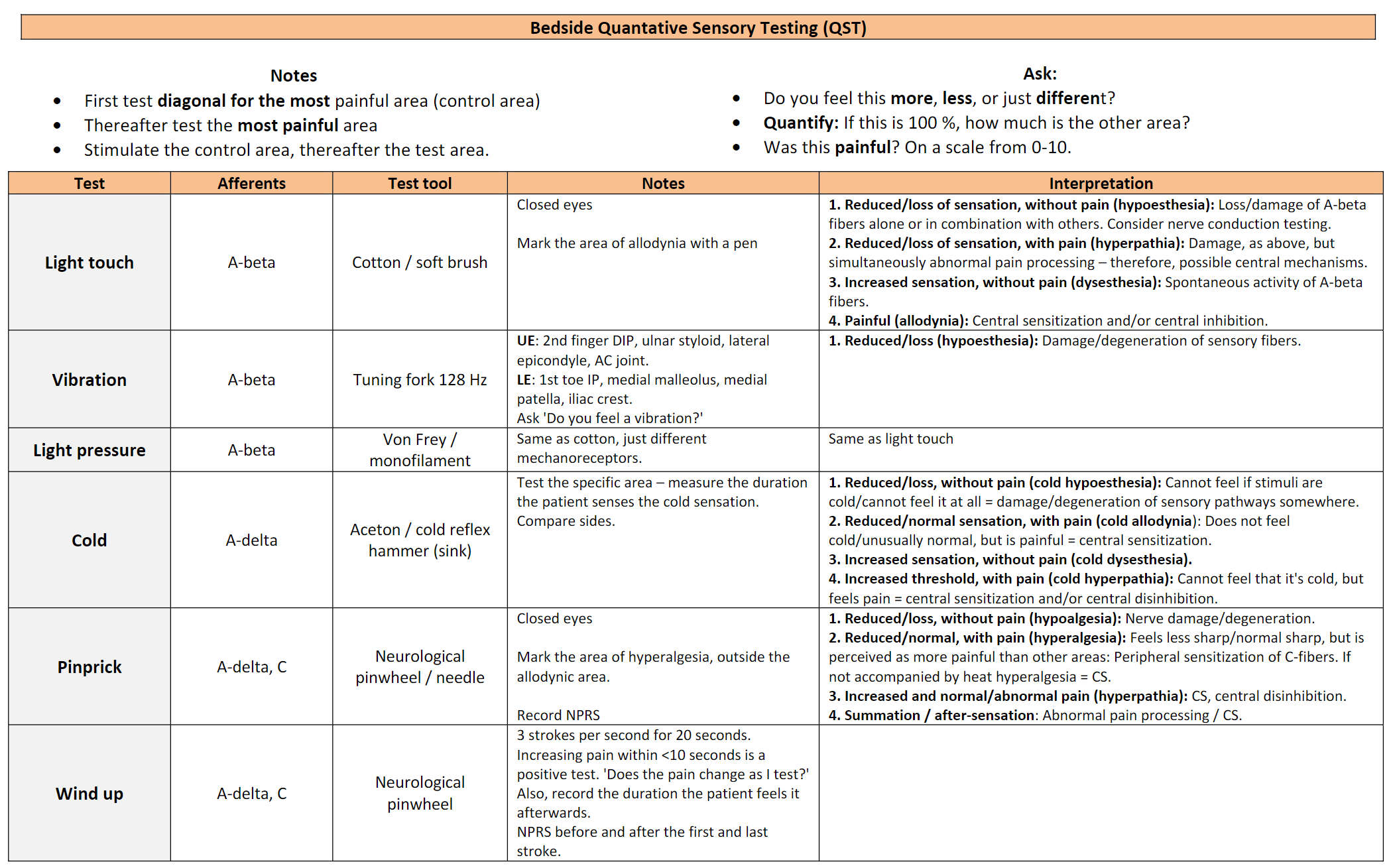

Compression of a nerve can damage both the nerve itself and the blood vessels within it, primarily along the nerve’s edge. In relative terms, the large nerve fibers experience greater deformation compared to the small ones, making them more prone to damage (5). Neurological diagnostic tests primarily assess the large fibers. For instance, light touch is a test of the thick, myelinated A-beta fibers. Schmid et al. (7) have more recently observed that thin nerve fibers can also be affected by entrapment neuropathy, possibly even before the thick nerve fibers. Therefore, it is suggested that the function of small nerve fibers should also be assessed (7).

Mechanical deformation

Determining the exact amount and duration of pressure required to cause damage is challenging. Time is a significant factor. One study showed that direct pressure of 30 mm Hg resulted in reversible damage after 2-4 hours, while pressure beyond this level potentially caused irreversible damage. Compression at 400 mm Hg led to more severe damage after two hours compared to 15 minutes (5).

In the nerve root, a two-hour pressure of 50-75 mm Hg leads to a reduction in the ability to activate muscles, while a pressure of 100-200 mm Hg results in complete conduction block (paralysis), and it is uncertain whether recovery will occur from this state (5). For example, Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES) surgery is recommended within 48 hours from onset or earlier to prevent permanent nerve damage (8). A neurologist I spoke with recommended hospitalization within 72 hours for disc herniation with grade 3 or lower paresis, although this varies among hospitals and countries. The most commonly used methods to grade muscle paresis are likely the Oxford scale or the Medical Research Council scale of muscle strength (MRC-scale) (9).

Nerve root stretch

Amidst the discussion of compression, one should not forget that stretching of the nerve root can also lead to radiculopathy. It has been observed that a disc herniation can become attached to the dura mater of the nerve root (17). In a study, it was noted that this adhesion could result in traction on the sciatic nerve and consequently radicular pain. Surgery improved the movement of the nerve root (17). This has also been observed in another study where there was a significant difference in nerve root sliding before and after surgery (18).

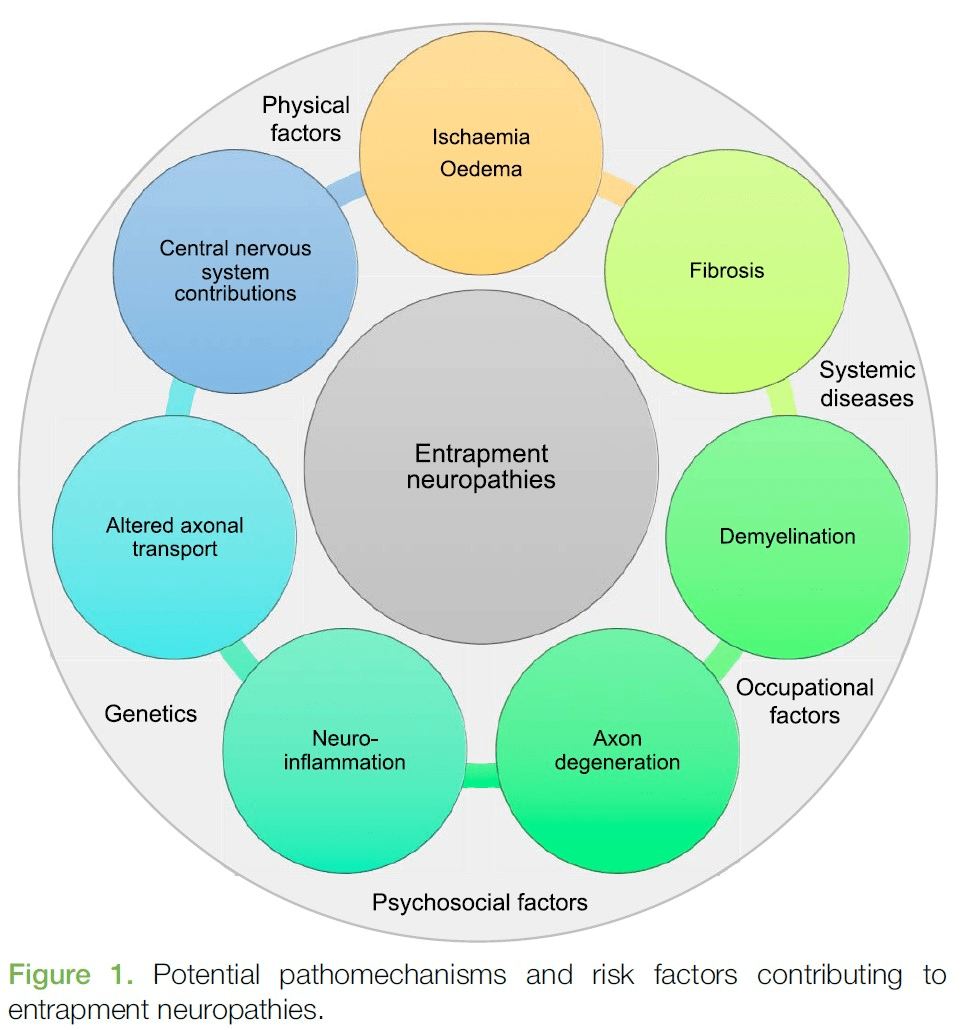

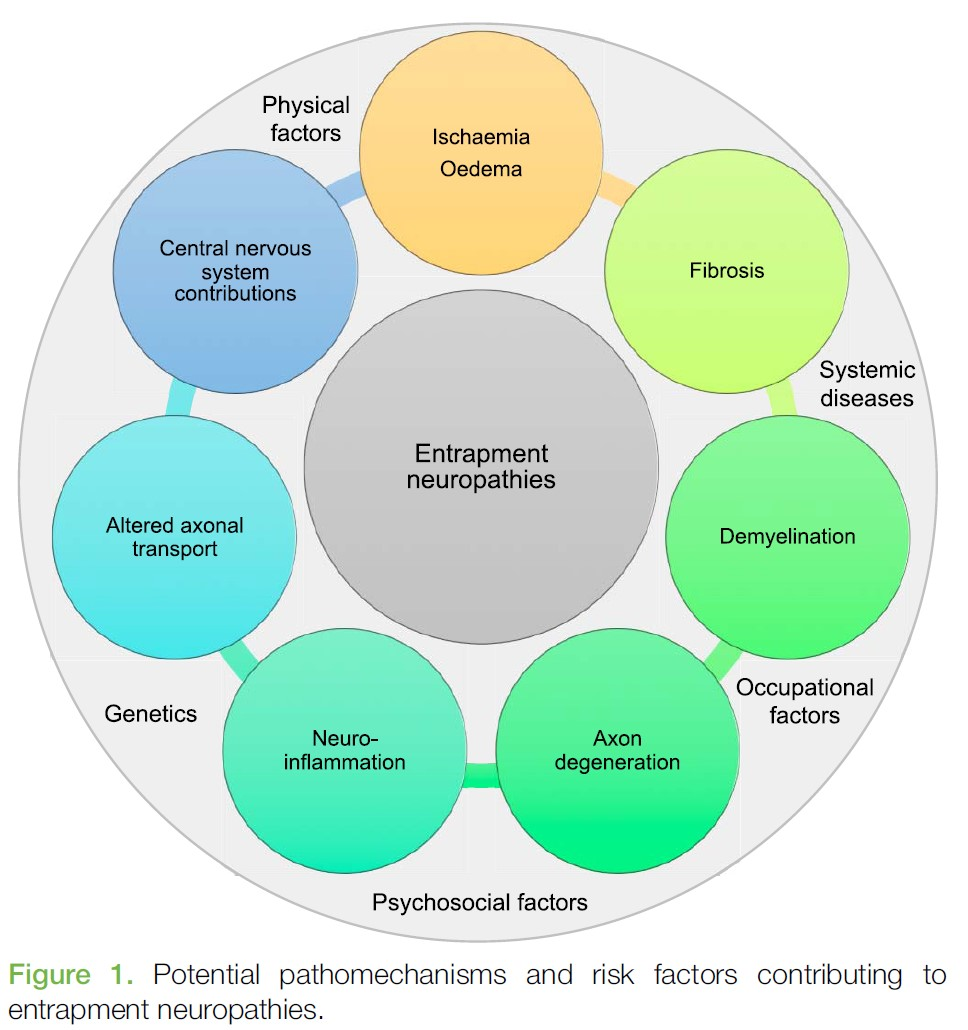

Nerve damage can lead to degeneration and a neuroinflammatory condition that can cause neuropathic pain. Both hyperalgesia and allodynia have been observed after prolonged pressure on a nerve (5). Pressure is not the sole factor. Inflammation without pressure on the nerve can also cause radiculopathy (10–12). Other factors are mentioned in the previous post, and Schmid et al. (7) have compiled this informative overview:

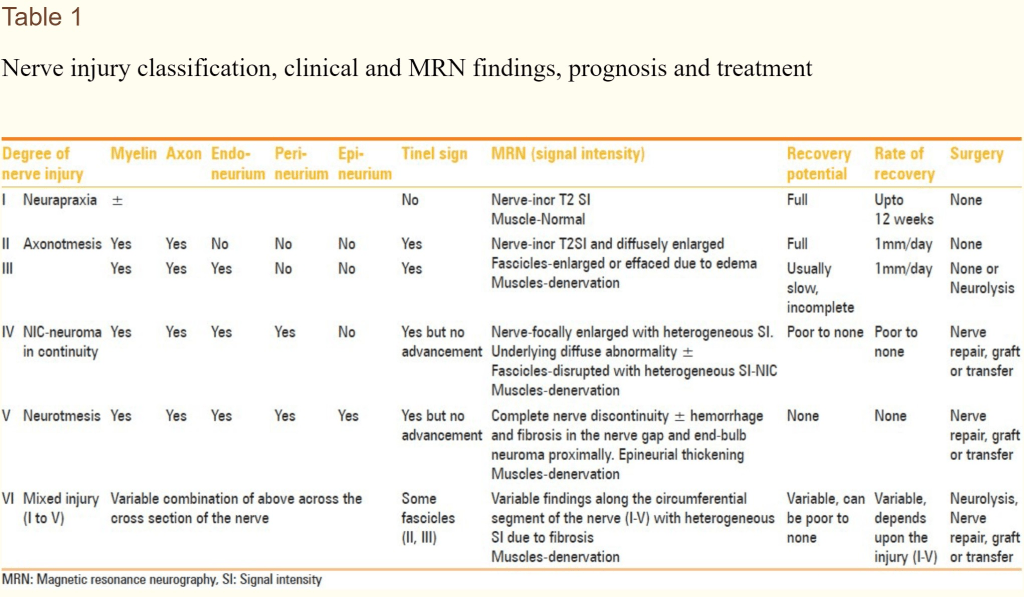

Classification

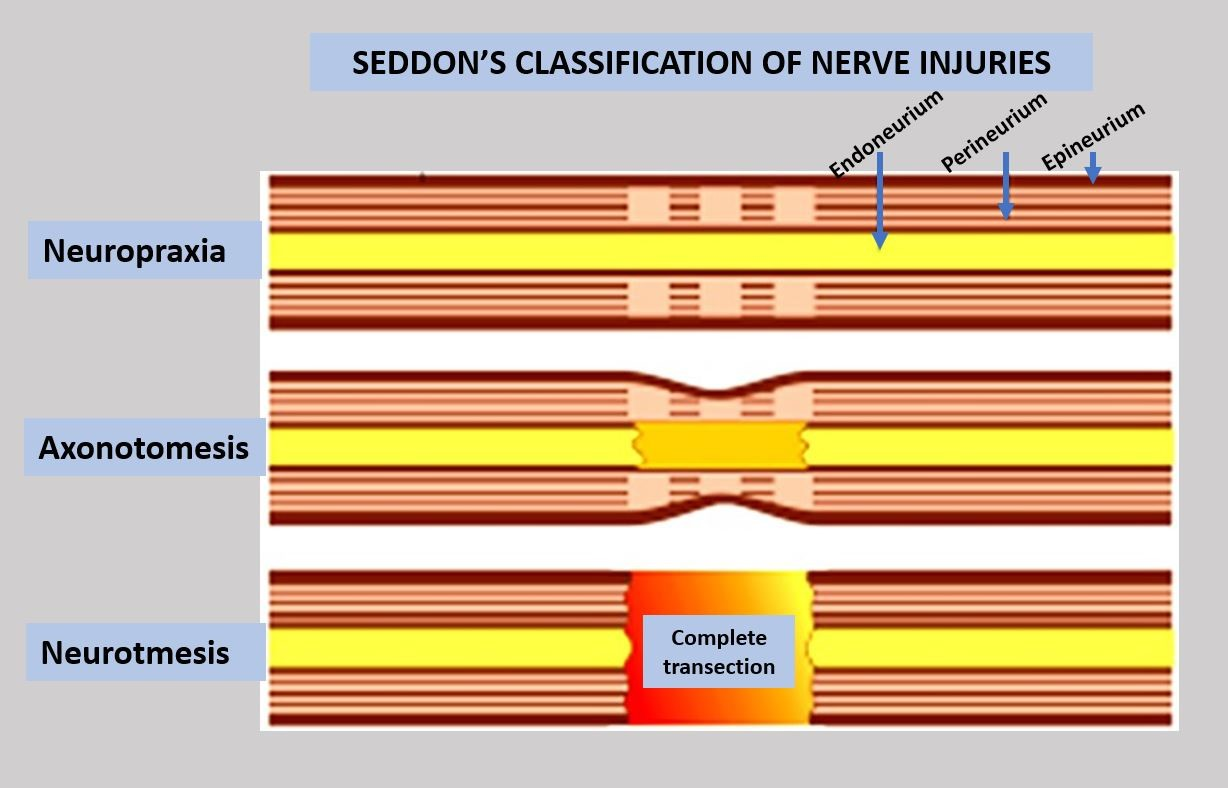

Peripheral nerve injuries can be classified, and the two most commonly used classifications are Seddon and Sunderland classifications, although these may be more relevant in crush/cut injuries (13).

Seddon’s classification divides nerve injuries into three categories.

Sunderland’s classification divides nerve injuries into five categories and is often used in surgical assessments (13).

The challenge with much of the research on nerve damage lies in its focus on acute and relatively severe injuries. A disc herniation can develop slowly, gradually exerting increasing pressure on the nerve. As described, even a pressure as low as 20-30 mm Hg can disrupt venous circulation (7).

The pressure gradient is a crucial concept here. The pressure from the arteries in the epineurium should exceed the capillary pressure in an axon bundle, which in turn should exceed the pressure within the axon bundle, and so on, as depicted in the image below (14).

However, nerve damage/radiculopathy is not a black-and-white issue. Nerve compression can be asymptomatic, as observed in MRIs (7). It has also been demonstrated that many individuals with radiculopathy, detected through neurophysiological examination, do not exhibit abnormalities in neurological diagnostic tests. A study showed that 31% of these individuals had no signs of muscle weakness, and 45% showed no change in sensitivity (15). Denervation becomes more evident after a few days/weeks after injury, and it takes longer for this to become visible in distal muscles compared to proximal muscles (16). Perhaps it is also advisable not to always label it as nerve damage? In a lecture, Per Brodal referred to it as ‘stunned nerve’ (if that translates well to English?).

Summary

Radiculopathy occurs when nerve conduction in a nerve is blocked, characterized by reduced strength, sensibility, and/or reflexes. Traditionally, it was believed that large nerve fibers were primarily affected, but it is now understood that small nerve fibers are also affected. Therefore, in addition to testing thick fibers, an examination of thin fibers should be included. Size, duration, and type of pressure are decisive factors in whether nerve damage develops.

References

1. Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 15. desember 2009;147(1–3):17–9.

2. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, mfl. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet Lond Engl. 09 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

3. Solberg AS, Kirkesola G. Klinisk undersøkelse av ryggen. Kristiansand: HøyskoleForlaget; 2007.

4. Lind P. Ryggen: undersøgelse og behandling af nedre ryg. 2. utg. Kbh.: Munksgaard Danmark; 2011.

5. Nordin M, Frankel VH, redaktører. Basic biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system. 4th ed, international ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. 454 s. (Wolters Kluwer Health).

6. Rosso G, Liashkovich I, Gess B, Young P, Kun A, Shahin V. Unravelling crucial biomechanical resilience of myelinated peripheral nerve fibres provided by the Schwann cell basal lamina and PMP22. Sci Rep. 2. desember 2014;4:7286.

7. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep [Internett]. 22. juli 2020 [sitert 24. september 2020];5(4). Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7382548/

8. Kapetanakis S, Chaniotakis C, Kazakos C, Papathanasiou JV. Cauda Equina Syndrome Due to Lumbar Disc Herniation: a Review of Literature. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 20. desember 2017;59(4):377–86.

9. O’Neill S, Jaszczak SLT, Steffensen AKS, Debrabant B. Using 4+ to grade near-normal muscle strength does not improve agreement. Chiropr Man Ther [Internett]. 10. oktober 2017 [sitert 14. november 2020];25. Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5633899/

10. Andrade P, Visser-Vandewalle V, Philippens M, Daemen MA, Steinbusch HWM, Buurman WA, mfl. Tumor necrosis factor-α levels correlate with postoperative pain severity in lumbar disc hernia patients: opposite clinical effects between tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2. Pain. november 2011;152(11):2645–52.

11. Chen C, Cavanaugh JM, Ozaktay AC, Kallakuri S, King AI. Effects of phospholipase A2 on lumbar nerve root structure and function. Spine. 15. mai 1997;22(10):1057–64.

12. Deyo RA. Real help and red herrings in spinal imaging. N Engl J Med. 14. mars 2013;368(11):1056–8.

13. Chhabra A, Ahlawat S, Belzberg A, Andreseik G. Peripheral nerve injury grading simplified on MR neurography: As referenced to Seddon and Sunderland classifications. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2014;24(3):217–24.

14. Sunderland S. The nerve lesion in the carpal tunnel syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. juli 1976;39(7):615–26.

15. Lauder TD, Dillingham TR, Andary M, Kumar S, Pezzin LE, Stephens RT, mfl. Effect of history and exam in predicting electrodiagnostic outcome among patients with suspected lumbosacral radiculopathy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. februar 2000;79(1):60–8; quiz 75–6.

16. Ropper AH, Zafonte RD. Sciatica. N Engl J Med. 26. mars 2015;372(13):1240–8.

17. Berthelot J-M, Laredo J-D, Darrieutort-Laffite C, Maugars Y. Stretching of roots contributes to the pathophysiology of radiculopathies. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(1):41–5.

18. Kobayashi S, Shizu N, Suzuki Y, Asai T, Yoshizawa H. Changes in nerve root motion and intraradicular blood flow during an intraoperative straight-leg-raising test. Spine. 1. juli 2003;28(13):1427–34.