What’s what?

When a patient comes to you with lower back and leg pain, it can be difficult to determine what exactly is causing this. Are the issues originating from the back? The sacroiliac joint? Hamstrings? Calf? And what do you call it? Referred pain? Sciatica? Radiculopathy? Neuropathy? Radiating pain? Nerve root affection? There are many terms. For me, it has been helpful to systematically categorize potential pain mechanisms and causes to the extent possible.

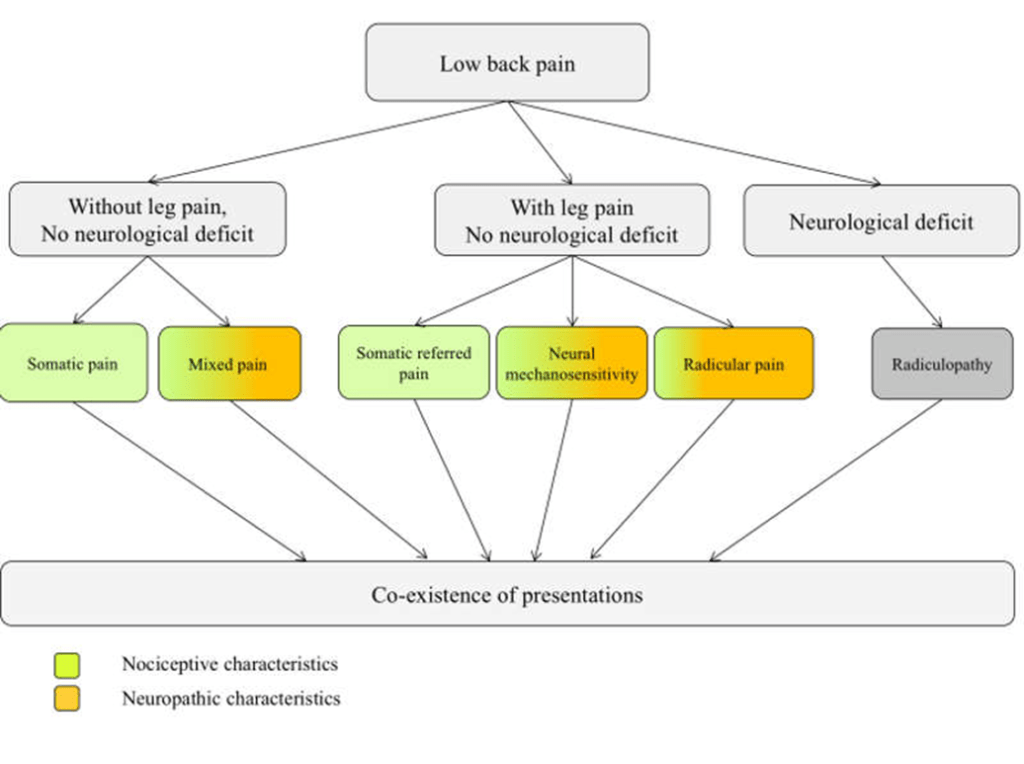

The spine researcher Nikolai Bogduk has a concise, informative article on the topic, which is also considered a sort of “golden standard” in the field. He categorizes it into nociceptive back pain, somatic referred pain, radicular pain, and radiculopathy (1). Perhaps somewhat reductionist, as pain can be seen as an output (2,3), but a useful tool in clinical reasoning. Radiculopathy and radicular pain are indeed two different things!

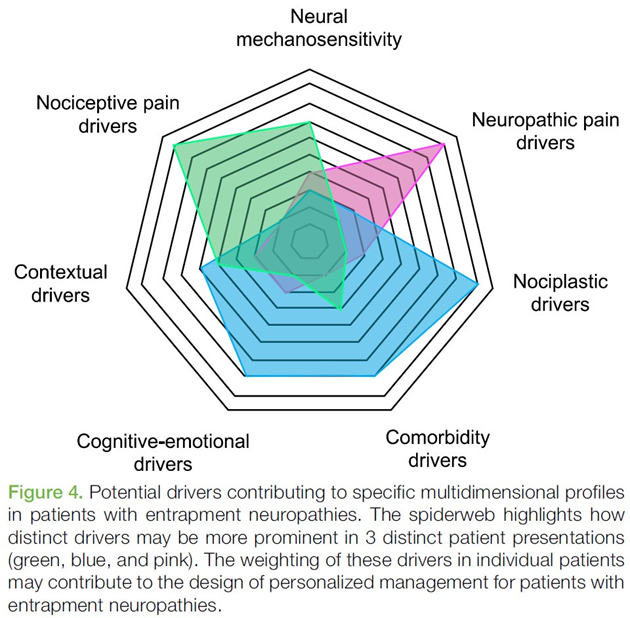

Schmid and Tampin have further developed these definitions to some extent (4). Many patients with chronic lower back pain with or without leg pain are not purely “either or”; they lie somewhere in the spectrum between “purely nociceptive” or “purely neuropathic.” Nociplastic mechanisms are also often present in patients with lower back pain, especially when it has persisted for a long time.

International association for the study of pain (IASP) operates with three types of pain, and Freynhagen et al. (2019) shows here that mixed pain is potentially present with a lot of patients.

Thus, there can be nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain drivers, and often it is a combination.

Radicular pain

When you have pain radiating down the leg due to a herniated disc and nerve root/ganglion involvement, it is called radicular pain (5). Colloquially, these pains are referred to as sciatica, but this term covers somatic referred pain, radiculopathy, and radicular pain. Radicular pain is therefore a more accurate term.

In 90% of cases, the cause of radicular pain is a herniated disc (according to one source) (6). The pain is often described as a thin band traveling down the leg, characterized by a piercing, electric, and/or stabbing sensation (1). Patients usually experience back pain as well, but the leg pain is typically worse (6,7). However, I also encounter patients with radicular pain only in the buttock region or even just in the calf. There are also cases where there is no pain in the back at all.

What Causes Radicular Pain?

A nerve root must be irritated to produce radicular pain. This was actually tested on humans (!) in a study from 1958 (credits to Tom Jesson for this finding of a study!). Eight patients were operated on for herniated discs and radicular pain. During the surgery, researchers placed a nylon thread around the nerve root and let it protrude from the surgical site when they were done. The patients were relieved of leg pain. One, ten, and fourteen days after the surgery, the researchers pulled the nylon thread at the site where the herniated disc had been, reproducing the leg pain. Other patients had nylon threads placed around locations other than the irritated nerve root, including the dura mater, ligamentum flavum, ligamentum interspinalia, and other nerve roots, but these patients experienced no leg pain when these threads were pulled (8).

Similar findings have been confirmed in other studies. For example, one study showed that one-third of patients with MRI-confirmed nerve root involvement do not have radiculopathy or radicular pain proportional to the MRI findings (9). On the other hand when examining MRI images of asymptomatic individuals, only 3-5% exhibit nerve root involvement.

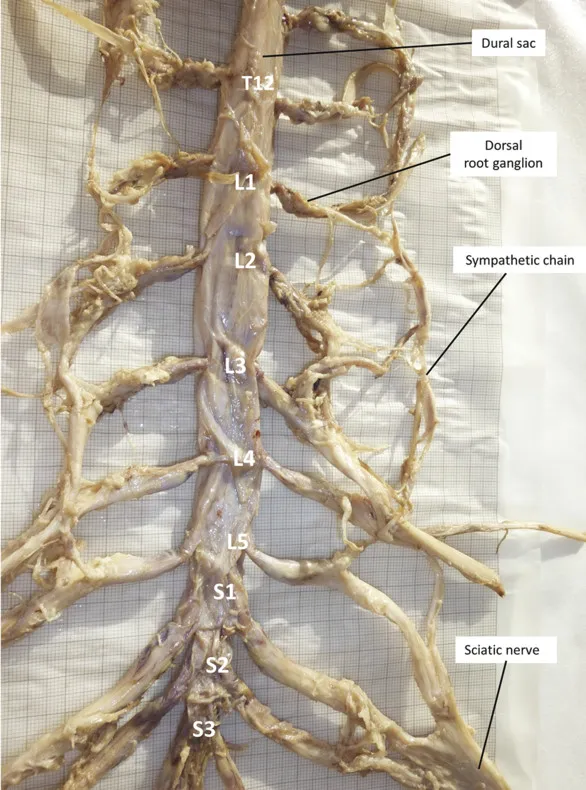

Other structures have the potential to cause more trouble. One of these is the spinal ganglion, where the cell body and nucleus of the nerve cell are located (10,11) (thanks again, Tom, credits to you and here is his article). The design of this cell is pseudounipolar, meaning one branch goes to the periphery and the other branch goes to the spinal cord. Quite ingenious, as it is “out of the way,” in what is called a T-branch (12). Nevertheless, it is curious to place such a potentially pain-sensitive structure (10,11) here, in the intervertebral foramen. Pressure on the spinal ganglion will generate a multitude of nociceptive action potentials, even if the nerve is healthy (13).

Thus, a nerve root must be irritated to cause radicular pain. This irritation can result from compression, edema, and intraneural fibrosis (5). Prolonged low pressure, such as from a minor herniated disc with slight nerve compression, can disturb venous circulation in the nerve. This can explain the experienced paresthesias that patients might feel at night, as it may start to prick/tingle/cause discomfort. Movement increases microcirculation and reduces paresthesia (5,14). This is why neural mobilization exercises can be effective. It is believed that this can reduce local edema and lead to neuromodulation (15,16).

Prolonged pressure and ischemia can also lead to demyelination and axon degeneration. This can cause the nerve to spontaneously generate action potentials, resulting in an electric shock-like pain when pressure is applied to the nerve, such as in the bowstring test (5).

Neuroinflammation can also be a cause of radicular pain. Neuroinflammation is characterized by the activation of immune cells (e.g., macrophages, T-lymphocytes) where the axon is damaged. This neuroinflammation sensitizes both damaged and undamaged nerve tissue (5). You might have heard and experienced that you can’t diagnose which nerve root in the lower back is affected based solely on where the patient feels pain? You might have also wondered why the patient has pain that doesn’t necessarily follow a dermatomal pattern, even though the MRI shows only one affected nerve root? Neuroinflammation could be the reason.

Annina Schmid and others suggest that this may possibly be due to an immune-inflammatory mechanism. They showed that compression of the sciatic nerve affected the spinal ganglion, which is far from the site of compression. This spinal ganglion contains thousands of nerve cell nuclei from other parts of the body. A general reduction in the firing threshold for action potentials could explain the spread of symptoms (18).

This neuroinflammation has also been observed in locations far from the initial site (19). This could explain the spreading of symptoms in cases of herniated discs.

In conclusion, compression is not the only cause of radicular pain, and the pain can subside even if the compression persists (14). So, when you have a patient with suspected herniated disc, it’s important to conduct a thorough neurological assessment, even if the patient doesn’t have leg pain.

Summary

There’s a difference between nociceptive pain, somatic referred pain, radicular pain, and radiculopathy. A nerve root must be irritated to cause radicular pain, while the spinal ganglion can cause pain independently of irritation. Compression, edema, intraneural fibrosis, demyelination, axon degeneration, and neuroinflammation can all be causes of radicular pain. Neuroinflammation can be the explanations for the spread of symptoms.

References

1. Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 15. desember 2009;147(1–3):17–9.

2. Melzack R. Pain and the neuromatrix in the brain. J Dent Educ. desember 2001;65(12):1378–82.

3. Gifford L. The mature organism model. :12.

4. Schmid AB, Tampin B. Section 10, Chapter 10: Spinally Referred Back and Leg Pain – International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. I: Boden SD, redaktør. Lumbar Spine Online Textbook [Internett]. 2020 [sitert 4. oktober 2020]. Tilgjengelig på: http://www.wheelessonline.com/ISSLS/section-10-chapter-10-spinally-referred-back-and-leg-pain/

5. Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep [Internett]. 22. juli 2020 [sitert 24. september 2020];5(4). Tilgjengelig på: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7382548/

6. Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 23. juni 2007;334(7607):1313–7.

7. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, mfl. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet Lond Engl. 09 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

8. Smyth MJ, Wright V. Sciatica and the intervertebral disc; an experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. desember 1958;40-A(6):1401–18.

9. Endean A, Palmer KT, Coggon D. Potential of magnetic resonance imaging findings to refine case definition for mechanical low back pain in epidemiological studies: a systematic review. Spine. 15. januar 2011;36(2):160–9.

10. Epstein NE. Foraminal and far lateral lumbar disc herniations: surgical alternatives and outcome measures. Spinal Cord. oktober 2002;40(10):491–500.

11. Park HW, Park KS, Park MS, Kim SM, Chung SY, Lee DS. The Comparisons of Surgical Outcomes and Clinical Characteristics between the Far Lateral Lumbar Disc Herniations and the Paramedian Lumbar Disc Herniations. Korean J Spine. september 2013;10(3):155–9.

12. Hogan Q. Labat Lecture: The Primary Sensory Neuron: Where it is, What it Does, and Why it Matters. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(3):306–11.

13. Devor M. Unexplained peculiarities of the dorsal root ganglion. Pain. 1. august 1999;82:S27–35.

14. Adams MA, redaktør. The biomechanics of back pain. 3rd ed. Edinburgh ; New York: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2013. 335 s.

15. Ballestero-Pérez R, Plaza-Manzano G, Urraca-Gesto A, Romo-Romo F, Atín-Arratibel M de los Á, Pecos-Martín D, mfl. Effectiveness of Nerve Gliding Exercises on Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1. januar 2017;40(1):50–9.

16. Ellis RF, Hing WA. Neural Mobilization: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials with an Analysis of Therapeutic Efficacy. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(1):8–22.

17. Lee MWL, McPhee RW, Stringer MD. An evidence-based approach to human dermatomes. Clin Anat N Y N. juli 2008;21(5):363–73.

18. Schmid AB, Hailey L, Tampin B. Entrapment Neuropathies: Challenging Common Beliefs With Novel Evidence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):58–62.

19. Albrecht DS, Ahmed SU, Kettner NW, Borra RJH, Cohen-Adad J, Deng H, mfl. Neuroinflammation of the spinal cord and nerve roots in chronic radicular pain patients. Pain. mai 2018;159(5):968–77.